Farmers pay for weather forecasts after losing faith in bureau

Some farmers say the weather bureau is getting it wrong too often and have resorted to paying for their own weather forecasts.

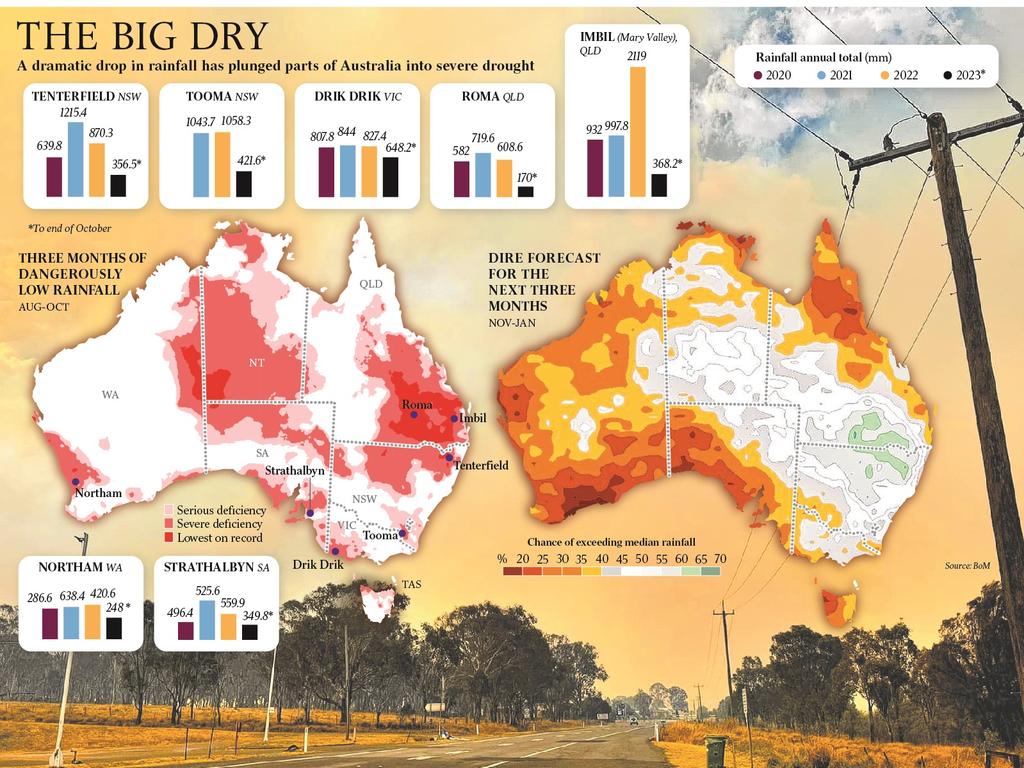

Some farmers have turned to paying for weather forecasting services because they have lost faith in the Bureau of Meteorology, blaming “inaccurate” predictions of a dry spring for sparking a rush among producers to sell their livestock.

The massive supply of sheep and cattle into markets around the country in winter and spring contributed to a steep fall in prices at saleyards as farmers offloaded their stock to pre-empt drought while the bureau forecast an El Nino-induced dry spring.

Early spring rain was scarce, but there was significant falls in parts of the country in November, causing some farmers to regret selling their stock while prices were so low and they feared they would not have the pasture to feed their animals.

South Australian cattle producer and restaurant owner Timothy Burvill, who also runs stock in NSW, said he and other farmers had grown distrustful of the bureau and were paying for their own weather services.

He did not heed the bureau’s forecast and chose to hold onto his stock, banking on the forecast of his own provider that predicted a wet November.

“How can a small business like that predict the weather more accurately than a massive organisation like (the bureau)?” Mr Burvill said.

“I don’t think anyone expects that medium-term weather forecasts are going to be super accurate, but with all the computer power we have at the moment, you would expect more.

“They have to be held to account for the inaccuracies of their performance this year. It’s had a massive impact on livestock markets.”

Mr Burvill said farmers he knew were “distrusting” of the bureau and that other weather models were more accurate in predicting monthly rainfall and longer range outlooks.

“I think it has got to do with what they are putting into their forecasting models to keep getting these dry forecasts,” he said.

“I’m not the only one who feels this way, there’s tens of thousands of farmers who don’t trust what they are talking about so they go and pay to get a weather forecast.”

Mr Burvill said the media also had a role to play in accurately reporting forecasts.

The bureau was one of the last major global meteorological services to declare an El Nino was in effect and the service’s climate services manager, Karl Braganza, said the forecasts were more nuanced than what was often interpreted.

He said climate drivers like El Nino, which typically heralds a hot, dry spring in eastern Australia but has less effect on summer rain, were indicators of atmospheric conditions, and not necessarily a reliable predictor of rain or weather.

“The problem with basing (forecasts) off those climate drivers is that the background state keeps changing,” Dr Braganza said.

“The oceans are now a lot warmer than a lot of the historical analogs that the climate drivers are based on.”

Dr Braganza said the bureau was wary of placing too much emphasis on El Nino declarations and that dry conditions in early spring were influenced more by the Indian Ocean Dipole than El Nino, which was counteracted by warm sea surface temperatures in the Tasman Sea, bringing rain in November.

“We saw a really dry spring up until November, then we’ve seen a rainfall event come in,” he said.

“At this time of year, when the El Nino breaks down, there’s almost no use in looking at it.

“Models have been consistent in saying that there were more neutral odds for rainfall as we got into summer.

“Some people are getting excited about this one rainfall event, but when we look back at recent history, about half of the El Ninos had a rainfall event in November.

“If it dries out again in December, people will forget about this rain.”

Dr Braganza said terms like “super El Nino”, used in some media reports but not by the bureau, had contributed to confusion around predicted rainfall.

The bureau’s spring outlook predicted below median rainfall was “likely to very likely (60 per cent to 80 per cent chance) for most of Australia”.

What eventuated was among the driest September and October on record, followed by above average November rainfall across most of the mainland.

“For Australia as a whole, spring rainfall was 20.1 per cent below the 1961–1990 average,” according to the bureau’s season summary, released on Friday.

Cattle and sheep prices have fallen steeply over the past year and analysis of saleyard data shows a significant increase in stock being sold since talk of El Nino early in the year.

Since rain began to fall in November, prices have rebounded by about 30 per cent.

Mr Burvill’s concerns about the effect of weather forecasts on livestock producers have been echoed in the rural media by farmers, livestock agents and livestock industry advocates.

Episode 3 analyst Matt Dalgleish said that after three wet La Nina years, many farmers had responded to noticeably drier conditions even without the bureau’s forecast.

“The forecasts they (the bureau) put out were pretty dire and it didn’t quite eventuate, but it’s difficult when forecasting weather,” Mr Dalgleish said.

“We had three good consecutive seasons and, historically, there’s never been a time with four seasons of good rainfall in a row.

“Any producer who has been around for more than a few cycles would have already had a view to prepare for a bad season.

“I think that all contributed to the loss of confidence in the (cattle and sheep) markets.”

Stock and station agent Patrick Purtle, who is based in Manilla, near Tamworth in NSW, said the eagerness among producers to sell their livestock when the season turned was likely influenced by memories of the 2019 drought.

“I’ve never seen people’s attitudes so fragile and I think that’s a hangover from that drought,” he said.

“Seriously, every forecast you’d get said it wouldn’t rain until March next year, and the onset of El Nino. That and the (fragile) attitude, affected the market.

“It’s not fuelled entirely by the weather forecast, but that added fuel to the fire.”

Mr Purvey said rain over the past few weeks had contributed to prices rising by up to 50 per cent in some regions as producers withheld their stock.

“All of a sudden, people have feed and the attitude has changed,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout