Employers seek wage fines delay

Business demands two-year delay to new penalties for ripping off workers in latest push for changes to government’s IR bill.

Business is demanding a two-year delay to tougher new penalties for companies ripping off workers, increasing pressure from both employers and unions on the Morrison government to make changes to its industrial relations bill.

As business groups expressed anger at a union campaign to water down the bill, ACTU secretary Sally McManus said unions would press for a raft of changes and warned that the government was “delusional” if it thought it could sell “politically poisonous” laws that could leave workers worse off.

Escalating the political fight that dominated the final parliamentary week of the year, Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry chief executive James Pearson wrote to Industrial Relations Minister Christian Porter calling on the government to delay applying increases in penalties for wage underpayments to small business until 2023.

The emerging campaigns by employers and unions to force different amendments to the bill pose further challenges for the Coalition, which is seeking to introduce laws affecting the pay and conditions of workers for the first time since John Howard’s WorkChoices regime.

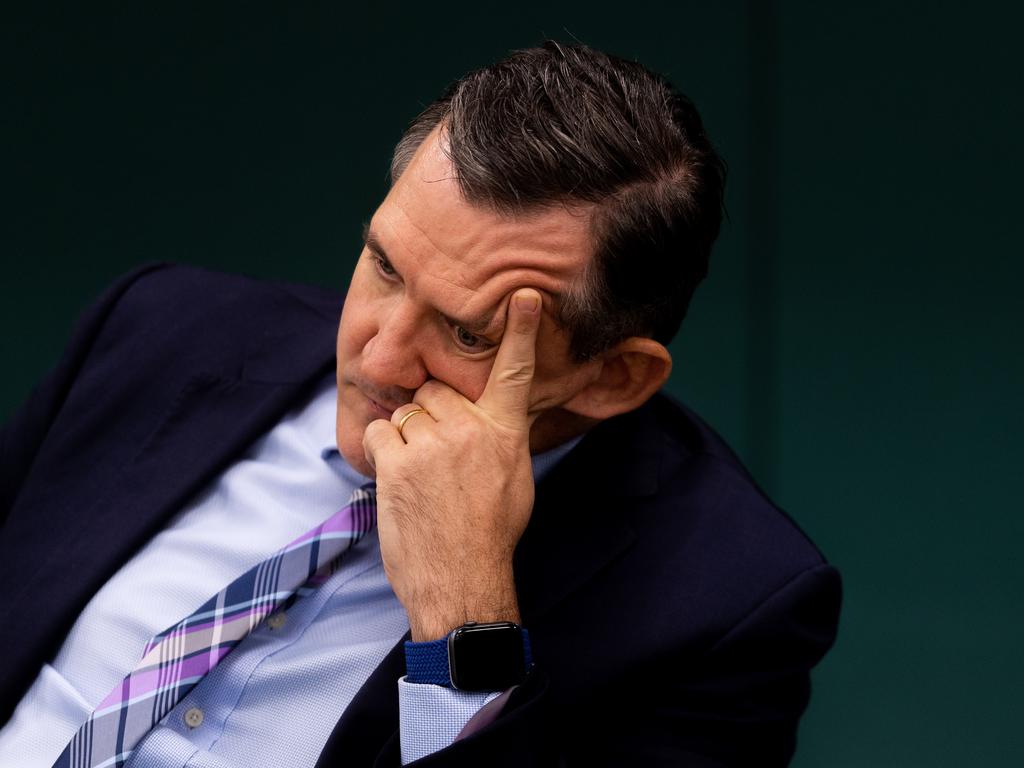

In response to Mr Pearson’s call, Mr Porter said on Thursday night the bill’s introduction was the start of the next round of consultations. “I’m sure there’ll be many views presented to the government and to the Senate committee (that will scrutinise the changes),” he said.

“Those views will all be considered as we move towards consideration of the bill next year. Reasonable suggestions that further improve the bill’s primary aim — to grow jobs — will be given particular attention.”

Under changes that employers want delayed, criminal sanctions, including jail and multi-million-dollar penalties, would apply to companies found to have dishonestly engaged in deliberate and systemic wage theft of employees. The new offence would carry a maximum penalty of up to four years’ imprisonment or a $1.1m penalty — or both — for individuals, and up to $5.55m for a body corporate.

Mr Pearson said the chamber’s members had expressed “grave concerns at the risk of immense fines, or even imprisonment, during one of the worst economic crises most of us have ever faced; and at a time when the community needs them, more than ever, to save and create jobs”.

“No one supports under-payment, but we need to get the balance right,” Mr Pearson told The Australian.

“So ACCI is calling for a delay in any further increase in fines against people in small business for two years; and to delay the commencement of criminal penalties, at least for people in small business, for two years.

“Even further ramping up penalties, on top of a recent tenfold increase still flowing through the court system, is not going to help make businesses any more confident to take risks, create jobs, invest or recover at this crucial time.”

The government is also proposing that workers be able to use the small claims processes through the courts to seek to recover up to $50,000 in unpaid wages, a $30,000 increase on the current cap.

Unions have expressed support for the measure, and the increase in civil penalties, but oppose the “high bar” set for criminal offences.

While Mr Porter could dump or modify changes that allow distressed companies to strike agreements that do not comply with the “better off overall” test (BOOT), the ACTU will also press for further changes relating to casuals, enterprise bargaining and greenfields agreements.

“I think that anything in this bill that is going to leave people worse off is going to be politically poisonous,” Ms McManus said. “If they think that somehow they‘re going to be able to sell that, they’re delusional.”

Anthony Albanese said Labor would vote against the bill if the government’s proposals for ¬casuals and the plan to allow COVID-affected employers to reach agreements that did not comply with the “better off overall” test remained in their current form. But the Labor leader did not entirely rule out supporting the bill if satisfactory changes were made.

Referring to the political storm over the changes to the test, Mr Porter said the focus had been on four paragraphs on one page so far, and he expected the provision, if passed, would be used by a very small number of companies.

He ruled out distressed companies being required to meet a turnover test as part of the eligibility criteria for a non-BOOT compliant agreement.

“I think that a turnover test would be totally, you know, unworkable,” he said.

“But in these circumstances where all parties would have to agree, where the business would have to be impacted by COVID, obviously in a negative way; and where the Fair Work Commission would have to determine that, in those circumstances, it was not against the public interest to have a modification to an award provision, they would be a tiny handful of cases …”

Business Council of Australia chief executive Jennifer Westacott said she understood the concerns about the “better off overall” test proposal but it was a temporary change that would only allow the test to be “bypassed in extreme circumstances”.

“First of all, this is an existing provision,” she said. “Secondly, both parties have to agree. Employers and employees have to agree. So, if you‘re being represented by a union they have to agree. Thirdly, you have to go to the Fair Work Commission, and they have to agree. Finally, it has to meet a public interest test and has to be for COVID-related matters. So, I can’t see this being used very often.”

Mr Pearson said it was important to recognise that the bill “represented significant success for unions”.

He said casual employees would have greater choice in staying casual, or seeking to work full or part time, while the bill will end the “last remnants of the WorkChoices era, ending the legacy application of pre-2009 enterprise agreements”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout