The women behind one of Australia’s best galleries reflect on art, friendship and international success

For 20 years, Sullivan+Strumpf has championed Australian contemporary art on the global stage. Founders Joanna Strumpf and Ursula Sullivan celebrate the milestone.

When Joanna Strumpf was in her early 20s, working at an auction house in a job she was steadily falling out of love with, sometimes, just to raise her spirits, she would pick up her desk phone and call her best friend Ursula Sullivan. “Sullivan and Strumpf Fine Art, Joanna speaking,” she would trill down the line.

It was easy to say those words but harder to realise them. When the two first met at the age of 22 – “babies, really, just out of uni,” Sullivan says – they had both recently arrived in Sydney from their native Brisbane to take up jobs with an art dealer. They shared tastes and values, and would often talk about one day starting their own gallery, but it would take almost another decade for the pair to sign the lease on a space in Paddington and open for business.

On an afternoon in November, Strumpf re-creates those phone calls, a faux landline clamped to one ear. She is sitting next to Sullivan in a meeting room adorned with works from their celebrated stable of artists on the second floor of the industrial Zetland space that now bears both their names above the door. Next month, Sullivan+Strumpf will celebrate its 20th anniversary. (They dropped the ‘Fine Art’; it’s cleaner.) For the best friends and business partners who dreamed of a gallery of their own all those years ago, this is only the beginning.

The early days of the gallery, which opened its doors to the public in March 2005, were, in a word, intense. “We honestly didn’t know what we were doing,” admits Sullivan. “Everything has been feeling around in the dark, really.” Within a few years of opening, both women also had their first children. “When our kids were little, we spent even more time together,” laughs Strumpf. “We had Mondays off, and sometimes we’d be together on Mondays as well, because we just needed the babies to be together.” Juggling a growing business and the demands of a young family, as well as maintaining a genuinely close friendship outside of the confines of a work partnership was, Sullivan sums up, full on. “We’ve never really done things at half or three-quarter pace – it has always been let’s fill it to the brim and just push. We just have this compulsion to do it this way. Because if you’re not, then you’re like, I’m not really trying.”

For the first five years of the business, the pair circled a single question: What kind of gallery do we want to be? One of their earliest signings was the pioneering Australian abstract painter Sydney Ball. Strumpf fondly remembers his weekly visits, crawling up the road in his van bearing slabs of cake. His death in 2017 was “like losing a parent”, she admits, and Sullivan+Strumpf continues to represent his estate. Ball taught the pair the fundamentals of what it means to be a successful gallery. “It’s about understanding that the artists are the most important thing you look after,” Strumpf says.

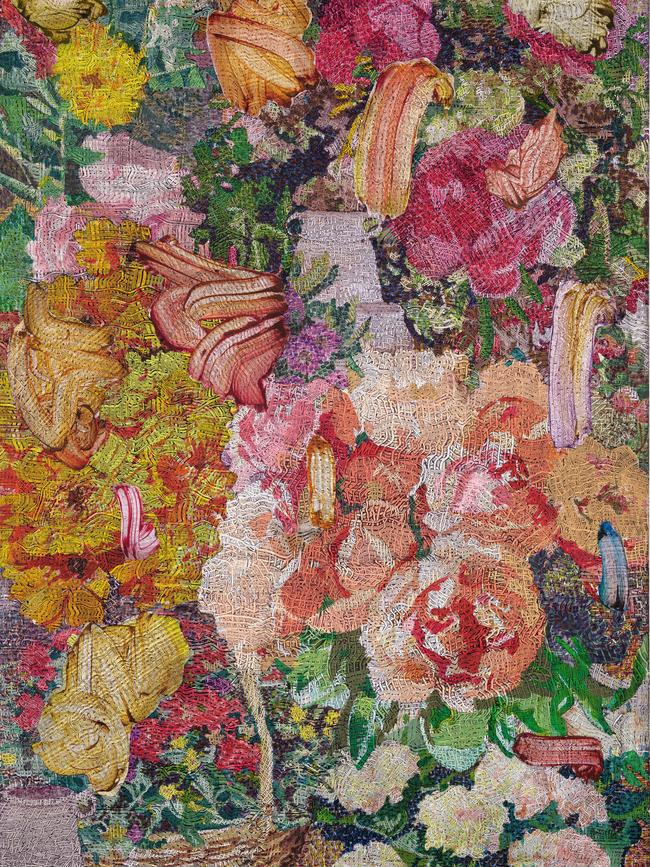

Today, the gallery represents 44 artists, ranging from Angela Tiatia and her hypnotic video installations to Tony Albert and his acclaimed works centring Indigenous histories. The highlights are too frequent to list, suffice to say that when it comes to the Archibald Prize, one of Australia’s most prestigious cultural accolades, Sullivan+Strumpf’s artists have won three times. (Sam Leach, Yvette Coppersmith and, in 2023, Julia Gutman.) “Every time a museum buys an artist” is a highlight, adds Sullivan. “And any time an artist has a show, that’s such an achievement.”

Of their creative stable, Sullivan notes, “We don’t really want two of the same.” The meeting room where the duo sits this afternoon is representative of that. On one wall is Sydney Ball’s Sonnets for the Portuguese (1974); on the other, the exuberant Coordinate (2024) by Gemma Smith, salmon pink peeling back to reveal brushstrokes of forest green and ochre. To the pair’s left is Polly Borland’s Ropey (2024), an undulating figurine the colour of freshly churned butter, and in front of them sits the unmistakable silhouette of Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran’s textural ceramic, aptly titled Yellow Figure With Masks (2024).

If Sullivan had to draw a through line between the artists the gallery represents, it would be a strong focus on materiality and use of colour; think of the many-layered strands of one of Julia Gutman’s tapestries or the splotches of bleeding, brightly saturated ink on a Lara Merrett canvas. And, adds Sullivan, “what we do look for is a sense of ambition”.

Because Sullivan and Strumpf have ambition, too. The business now boasts outposts in Melbourne and Singapore. In October, Sullivan+Strumpf’s debut booth at London’s prestigious Frieze Art Fair was a sell-out success. In high demand were works by Gregory Hodge, the Paris-based abstract painter, and Lindy Lee, fresh from the unveiling of her $14 million stainless steel conchiform Ouroboros at the National Gallery of Australia, a shimmering, mesmerising triumph and the institution’s most valuable commission. “In fact, the month of October was good for Sullivan+Strumpf,” says Strumpf.

On top of all this, out of Frieze, the Tate Modern acquired Naminapu Maymuru-White’s Miliyawuy (2024), a work of celestial beauty inscribed on bark.

The pair has witnessed great evolution in the local art scene in the two decades since the gallery opened. “The rise of the female collector,” nods Strumpf. “At the same time, the rise of the female artist, too. There are collectors consciously seeking out great female artists because that’s what they want to focus on.” Because, as Sullivan says, jumping in to continue her business partner’s thought, “It’s who they resonate with.” Looking to the next 20 years, Sullivan and Strumpf’s ambitions are clear. “We’d like to have an artist represent Australia at the Venice Biennale,” says Strumpf. “The next step for us is a big international exhibition for one of our artists. That is something to aim for, and totally within reach for quite a number of our artists.”

If there’s a secret to their success it’s that “there are two of us, so we can do a lot more”, Strumpf says, only half joking. “I think having two different eyes making decisions is also a huge advantage,” she adds. “Because it’s coming from two different aesthetics, we’re able to create something that’s really quite unique.” Two voices can dilute a message or it can bolster its impact. “In our case,” says Sullivan, “it’s really enhanced, because everything is thought about really thoroughly from two different perspectives.” If they differ – and it’s rare – there’s value in that opposition. “If she’s really passionate about something, if she really wants an artist, unless I feel very strongly in the opposite direction I agree with her and let it go,” stresses Strumpf. “Because when you both have to agree to something, something gets lost.”

Sullivan praises Strumpf’s emotional intelligence. “She’s a great people person, and can understand people’s values and where they’re coming from,” she says, while Strumpf blushes.

In return, Strumpf calls her business partner “a visionary”. “She’s looking three steps forward at all times, whereas I’m trying to figure out which way I move the chess piece.”

All those years ago, when Strumpf was working in that job at the auction house that was wearing her down, she thought she might leave art behind altogether. “I was having to handle a lot of very ordinary art … It was just not what I wanted to be doing,” she admits. “Which was very hard for me because I had wanted to be an art dealer since I was 15 years old, and I was ready to give it all away.” At her lowest moment, Sullivan called her with the name of an artist she was excited about, urging her to purchase some of their works. “Maybe we could do this when we open our gallery,” she encouraged her friend. “I was like, ‘I’m back. I know exactly what I want to do.’” Strumpf says, smiling at the memory. “Ursula brought me back to what I love.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout