Was that a real van Gogh at the garage sale?

A team of specialists is trying to prove that a canvas bought for less than $US50 was painted by the iconic artist — and is worth $US15 million.

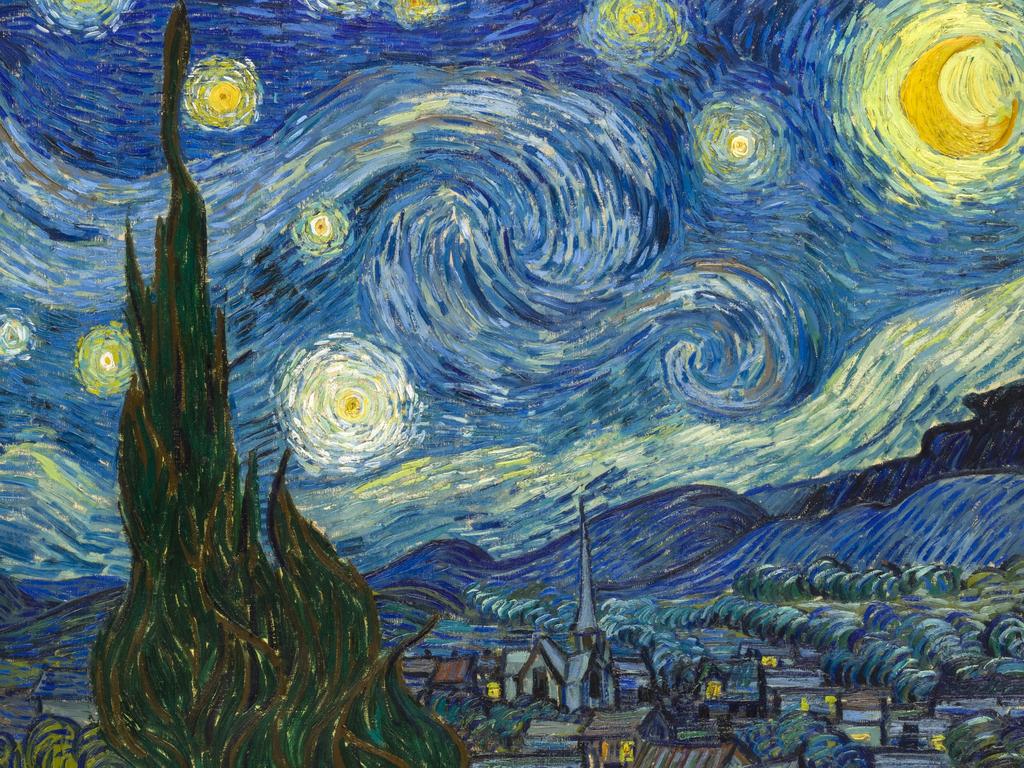

In 1889, Vincent van Gogh committed himself to a psychiatric asylum in southern France, where he spent a turbulent year creating roughly 150 paintings, that included masterpieces such as Irises, Almond Blossom and The Starry Night. Now, a former curator of ancient art at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art has teamed up a with a group of conservators, scientists and historians who believe they’ve discovered No. 151 – a previously unknown van Gogh portrait of a fisherman plucked from a Minnesota garage sale a few years ago by an unsuspecting antiques collector for less than $US50 ($80).

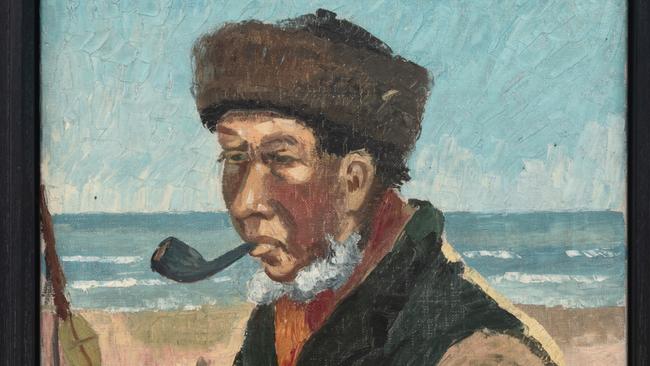

The thickly painted piece depicts a pensive fisherman with a white chin-beard and a round hat who clutches a pipe in his mouth as he repairs his net on an otherwise empty beach (pictured right). In the lower right hand corner, the name Elimar is scrawled.

The discovery could represent a notable addition to the oeuvre of one of the world’s most famous artists. Elimar could also prove to be a lucrative windfall for LMI Group International, the New York-based art-research firm that bought the work from the anonymous antiques collector for an undisclosed sum in 2019 and has investigated it ever since, pouring in well over $30,000 and involving a team of around 20 experts from disparate fields, from chemists to curators to patent lawyers.

Later this month, they will begin unveiling their find in private viewings to major van Gogh scholars and dealers around the world. They believe it is worth at least $15m.

But is it really a van Gogh?

“That’s the big question,” says Richard Polsky, an art authenticator who wasn’t involved in the project. “People love it when things fall through the cracks, and it would be wonderful if they found a van Gogh – but they’ve got to pin everything down and get a scholar at the van Gogh Museum to sign off on it.” Doing so could prove to be a tall order. The discovery, if accepted, comes at a time when artist foundations and estates are increasingly shying away from making ultimate rulings on the authenticity of artworks for fear of being sued by owners who aren’t happy to hear that their works aren’t authentic. Museums touting deep holdings in certain artists like Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum turn down most would-be examples shown to them.

The Van Gogh Museum declined to comment on LMI Group International’s purported version, but said it had a rigorous procedure in place to sift legitimate finds from fakes and pieces misattributed to the artist. Until a few years ago, the museum said it was shouldering up to 200 authentication requests a year, “99 per cent of which could not be attributed to van Gogh in our opinion”, a spokeswoman says. After requests recently surged to 500 a year, the museum altered its process to consider candidates only after they’ve first built up a groundswell of approval from galleries, auction houses or other art professionals. That amounts to about 40 hopefuls a year.

Maxwell Anderson, the former Met curator, is staking his reputation on Elimar being the real deal. Anderson, who went on to serve as director of New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art as well as other museums in Dallas and Indianapolis, was recruited to become LMI Group International’s chief operating officer in 2022 by the firm’s founder, art lawyer Lawrence Shindell.

The firm’s goal is to step into a perceived industry void and offer answers that combine scientific data with art-historical sleuthing – and ostensibly a financial upside as well.

The two men first learned of the painting’s existence in 2019, when an antiques picker in Minnesota called to say he’d spotted this fisherman in a bin of other paintings at a garage sale; he’d bought it because he liked the work’s impasto, or thickly painted brushstrokes, Anderson says. The buyer was told the garage-sale pieces may have previously belonged to the owners of a local antique shop.

That’s not much to go on, but Anderson and Shindell agreed to take a look. Standing before it in an art-storage facility in Manhattan, Anderson says he had been “struck by what he saw.” The piece lacked the vivid hues of van Gogh’s best-known pieces, but there were telltale signs of a deft painter at play, he says. He noted the confidently painted smile lines framing the older man’s mouth, and he wondered about a cross that appears to have been cryptically scored into the green-glass floater in the net. There was also a red hair embedded in the paint.

“Was I all in? No,” Anderson says, “but I was super intrigued.”

From an art history perspective, Anderson thinks the fisherman differs from the artist’s vivid signature palette in part because it belongs to a series of modified copies of other artists’ works that van Gogh painted while he was hospitalised. During his stay, he often pored through books on old master painters and painted his own retooled versions. Van Gogh called them translations.

In 1890, he described his approach to his art-dealer brother Theo, writing that his intent was “not copying pure and simple” but rather “translating into another language, the one of colours.”

Museums haven’t focused on the 33 known translations painted by van Gogh during this shut-in period in part because they stand out from his instantly recognisable compositions, according to William Havlicek, an art historian who has written a book on van Gogh and was paid by LMI Group International to research this lesser-known subset of van Gogh’s works. Yet the marketplace considers them significant, with van Gogh’s version of a Jean-Francois Millet field worker, The Reaper (After Millet), selling for $US31m at Christie’s in 2017.

While scouring auction catalogues, LMI Group International researchers soon found what they now consider to be the inspiration for Elimar: Danish painter Michael Ancher’s 1870s-1880s Portrait of Niels Gaihede, a depiction of a fisherman in a similar hat with a pipe repairing his net that sold in a Copenhagen auction house in 2011 for $US4484, according to auction database Artnet.

In van Gogh’s day, Ancher was a popular member of a group of Scandinavian artists who hung out in the Danish village of Skagen and were known to paint outside like the French Impressionists who van Gogh already knew well. The fact that LMI Group International’s iteration includes the shape of a cross into the net’s floater could nod to van Gogh’s off-and-on religious zeal as the son of a pastor.

“As soon as we saw the Ancher, I knew we were right,” Havlicek says. The LMI Group International team has also posited, in a report that spans 450 pages, that van Gogh signed the work Elimar, rather than with his own name, using brushstrokes similar to those he used in an 1885 work featuring a Bible and a book by Emile Zola. (The E’s, M’s and A’s were nearly identical.) Since it’s widely accepted by van Gogh scholars that the artist didn’t sign dozens of his works, the lack of his traditional “Vincent” signature isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker.

Pigments nearly were, though. Jennifer Mass, president of Scientific Analysis of Fine Art, was paid by LMI Group International to study the work’s pigments and fibres, among other factors.

Mass quickly discerned that the thread count of the canvas aligned with those produced in van Gogh’s day, but one of the pigments used to paint the work did not: PR-50, an organic compound related to the popular red pigment known as geranium lake, which provided the violet hues in the sky. Conservators commonly credit this compound to a French patent from 1905-06, which would have dated the work after van Gogh died in 1890, Mass said.

But since every other pigment checked out, she wondered if an earlier patent may have existed. Ben Appleton, a patent lawyer with Wilson Gunn, was hired to search without knowing the purported artist behind it all.

Appleton says France hadn’t routinely published its patents until after 1902, so hunting for anything earlier involved scouring scanned copies of handwritten documents.

After a month of following a breadcrumb trail of chemical manufacturers across Europe and the US, his firm found it: an 1883 patent for PR50 was registered by the Coloured Materials and Chemical Products of Saint-Denis, a Paris suburb.

Van Gogh’s paints were supplied by his brother Theo, who lived in Paris, according to the brothers’ published letters.

Mass says the revelation amounted to a find-within-a-find for conservators, who can now date and authenticate works containing this red pigment to the late 19th century, rather than the early 20th. DNA analysis of the hair found stuck to the painting also confirmed it belonged to a person with red or reddish-brown hair.

All of this may help the fate of Elimar, which will now need to be paraded before a swath of van Gogh scholars if it hopes to garner the one thing that artworks universally seek: validation.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout