Vincent Van Gogh and the Seasons a bountiful harvest at Melbourne’s NGV

There are many misunderstandings about Van Gogh, including that he painted under the inspiration of insanity.

Vincent van Gogh was born in 1853 and died by apparent suicide in 1890; Arthur Rimbaud was born in 1854 and died after the amputation of a leg in 1891. These almost exact contemporaries, each only 37 at his death, became paradigmatic figures of the modern painter and poet, partly because of their remarkable talent, but equally because of their profoundly disturbed characters and tragic lives.

Rimbaud was a precocious genius who could compose sophisticated poems in Latin at 14 and made his mark as an avant-garde poet while still a schoolboy. He formed a relationship with the older and already famous poet Paul Verlaine, which ended in a quarrel in Brussels during which Verlaine fired a pistol at his young lover. But by 21 Rimbaud had turned away from poetry and spent the rest of his life travelling from Java to Cyprus, eventually settling in Ethiopia, where he traded coffee and occasionally arms.

GALLERY: See a selection of Van Gogh’s works in the exhibition

Vincent — as he preferred to be called, since only the Dutch can pronounce his surname properly — had a very different career path. If Rimbaud flowered precociously, then disappeared into a strange afterlife, Vincent struggled through a variety of jobs and relationships before finding his way as a painter; almost all of his great paintings were produced in a period of little more than two years before his death.

There are many misunderstandings about Vincent’s life and work, including the idea that he painted under the inspiration of madness. The truth is that he was always deeply neurotic, unhappy and alienated, and his family considered having him committed for insanity during his 20s. He suffered a psychotic breakdown at the end of 1888, followed by recurrent episodes in 1889 and 1890. He did not paint during these attacks, however, but only between them.

Another common fallacy is that Vincent toiled for years without recognition; this fits conveniently with modernist myths about the obtuse public and conservative art world failing to recognise avant-garde genius, but less conveniently with the facts. All the work that was later so greatly admired was done after he left Paris for the south of France early in 1888, where he worked in isolation for the next two years. Had he died in the winter of 1887-88, Vincent would today be a footnote in art history.

By the end of 1889, thanks to the efforts of his brother Theo, some of Vincent’s paintings had been shown and had attracted favourable comments. If he had continued to paint and exhibit in this way, his reputation would soon have grown; but his suicide both cemented the myth that he had been overlooked and propelled him into posthumous stardom.

The myth of Vincent has pushed his work to absurd prices at auction, and has more recently led to one of the more prominent art controversies of the past year or two — after the discovery of a so-called Caravaggio that was clearly never touched by the hand of Michelangelo Merisi. It was announced that a previously unknown sketchbook full of drawings by Vincent from the early period of his stay in Arles had suddenly been discovered in mysterious circumstances.

A specialist in Vincent’s work, Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, declared the sketchbook authentic. She secured the backing of an even more senior scholar, Ronald Pickvance, even though the experts at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam flatly declared the drawings to be forgeries. The sketchbook was duly published by a respectable French publisher, and the English edition is available from gallery bookshops in Australia: at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra and now at the National Gallery of Victoria as well. And yet that esteemed connoisseur Blind Freddie could tell that the supposed self-portrait on the cover was not done by Vincent. Inside too, the drawings are the sort of feeble pastiches a forger imitating the artist’s mannerisms and familiar motifs without really understanding his inspiration would produce.

What is most important to understand about Vincent is that his late vocation as an artist emerged from the failure of earlier aspirations. After attempts to make a career in the family art-dealing business and stints as a bookseller and teacher, Vincent became obsessed with religion and hoped to be a missionary. He was sent on a probationary appointment among the poor coalminers of the Borinage area, but behaviour that might have been considered saintly in the Middle Ages seemed deranged in the modern world, and he was sacked.

He spent a year or so wandering in a state of disorientation and misery, writing few letters and thus leaving little information about his activities. But by 1880 he had decided to become an artist. His inspiration came from pictures of the labours of the fields by Jean-Francois Millet and the early works are post-Christian images of harsh labour in a fallen world, of humanity expelled from paradise just as he had been expelled from the church.

There were more dramas: a broken heart and then cohabitation with a hopeless, drunken, pregnant and syphilitic prostitute. But eventually he found his way to the culmination of the first half of his painting career in The Potato Eaters (1885). By then Theo, who was working as an art dealer in Paris, urged him to come and see what the impressionists were doing.

By the time Vincent came to Paris in 1886, the movement had gained acceptance and new directions were represented by Seurat’s neo-impressionism as well as the art of Cezanne and Gauguin. Vincent grudgingly swapped his dark tonal style for the brighter palette of the impressionists, and subsequently produced a number of works in this manner — mostly minor contributions to late impressionism.

Something important happened when, in the spring of 1888, he decided to move to the south of France. As his letters say, he felt the lessons of impressionism melting away: he had never been interested in optical effects or the transient moment. He returned to the great symbolic themes that had inspired him from the beginning of his vocation as an artist: the perennial activities of ploughing, sowing and harvesting above all.

In a sense one can see his artistic development as dialectical in shape: beginning with the thesis of his early, heavy and grim peasant pictures, then the antithesis of impressionism which opened him to the possibility of a lighter and brighter palette, and finally, when left to his own devices, the synthesis of his own mature style, which is at once symbolic, expressionistic and brightly coloured.

By the end of October 1888, Vincent had persuaded Gauguin to join him in Arles, but this proved catastrophic: by Christmas the tensions between them erupted into the crisis in which Vincent attacked Gauguin with a razor and then cut off part of his own ear. Early in 1889, he voluntarily entered the asylum at Saint-Remy-de-Provence and there painted some of his best pictures, albeit interrupted by psychotic attacks.

The pinnacle of Vincent’s work comes in striking pictures that seem to express an ecstatic, pantheistic sense of nature, obliterating the old, gloomy and guilt-ridden Christian vision he had inherited. But he never entirely overcame this dark influence, as we can see for example in the little northern church at the centre of The Starry Night.

The psychotic breakdowns involved terrible religious hallucinations, too, and this is what convinced him, by early 1890, that he had to leave the asylum. He went north to Auvers-sur-Oise, where his unhappiness seems to have been exacerbated by the birth of Theo’s son, named Vincent in his honour: Theo had supported him for all these years and now he seems to have felt that he was a burden on the young family. Presumably this is one of the factors that drove him to suicide, although it can hardly be a coincidence that he chose harvest time to end his life.

The NGV exhibition includes many works from all periods of Vincent’s career, although the decision to present them in seasonal groups tends to confuse the visitor’s understanding of his development as an artist. It is hard not to suspect this choice was made to distract our attention from the fact that about two-thirds of the pieces in the exhibition are from the years before the move to Arles.

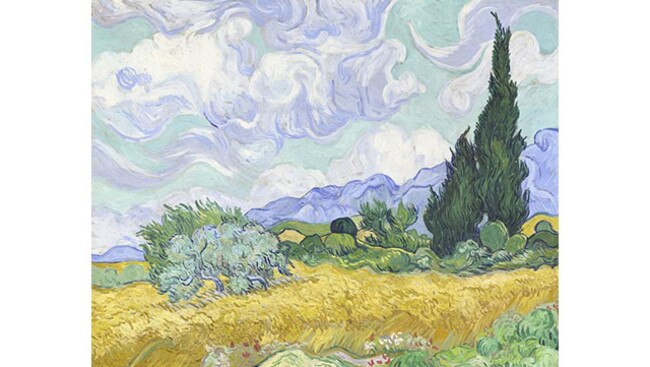

It would have been preferable to present the show chronologically and to cut a few of the earlier pictures. It is also a pity that the central theme of sowing and harvesting is not carried through into 1889. There are a couple of pictures from 1888 that deal with the subject, but one of the versions of the wheatfield seen from Vincent’s asylum window would have been at the top of my list for an exhibition such as this.

The exhibition design feels like a series of breakwaters intended to curb the surge of crowding visitors: first a theatrette with a documentary, then a room full of prints that belonged to the artist, then another room full of Japanese prints of the kind he admired — and then finally the main part of the exhibition, something of a labyrinth of spaces separated by screens. But nothing could mitigate the suffocating throng when I was there, made worse by the compulsion to take photographs.

Altogether this exhibition falls short of the admirable Degas survey last year. But one can take pleasure in several impressive early drawings, a fine view of Saintes-Maries with lavender fields in the foreground, a wheatfield from the summer and a vineyard from the autumn of 1888, and the September 1889 version of the beautiful A Wheatfield with Cypresses, which at least brings into focus the dramatic simultaneity of burgeoning life and impending death.

Van Gogh and the Seasons

National Gallery of Victoria, until July 9

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout