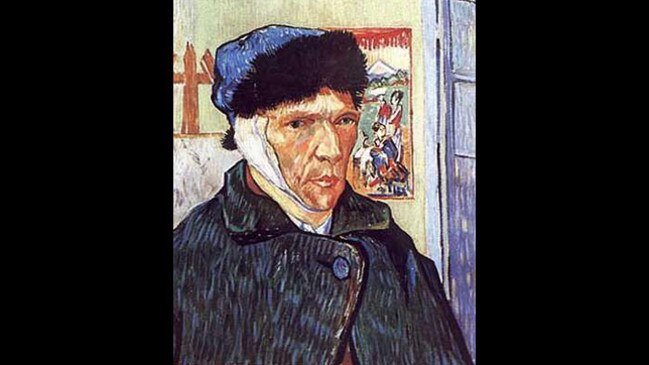

Van Gogh’s Ear: Bernadette Murphy goes beneath the bandages

How did a single event in a French provincial backwater 125 years ago come to define the painter Vincent Van Gogh?

How did a single event in a French provincial backwater 125 years ago come to define the painter Vincent Van Gogh? The sensational subject of his self-mutilation on Christmas Eve 1888 has been sleuthed with determination and delicacy by English author Bernadette Murphy and the result is an insightful and sympathetic portrait of a troubled artist.

Murphy arrived in Provence 30 years ago to visit a family member and then stayed. She learned the language, “stumbled from job to job” and bought a house in a little village 80km from Arles. The neighbourhood, she notes, has done well out of the lurid headlines of Van Gogh’s life. “Ever since I was a child I have enjoyed unravelling puzzles.”

Art lovers, novel readers and moviegoers have been introduced to Van Gogh in different ways. A generation of pop music lovers will remember the mournful song Vincent by American singer-songwriter Don McLean, while an earlier generation may have read the 1934 novel Lust for Life by Irving Stone, which was made into a staggeringly successful postwar movie starring Kirk Douglas. Painter Paul Gauguin, who would become famous for his depictions of Tahitian women and his louche life, clouded the records by giving one account of events at the time and a very different version 15 years later in his autobiography.

Murphy’s timing was fortuitous because when she began her project, propelled by the myriad discrepancies dispensed by locals to visitors, Van Gogh’s letters were being released online. Almost 800 have been posted to date.

Most are to his sympathetic, generous and long-suffering brother Theo, who dealt in impressionist paintings in Paris.

Murphy wondered what she could possibly bring to the case that had been raked over by so many experts and historians (quite a bit, as it transpired), but she did feel she had one advantage. Her decades in France had given her an insight into the Provencal mindset.

In the years since Van Gogh made his home in Arles, its physical shape has dramatically altered. The US Air Force earmarked the city’s railway bridge for destruction in preparation for liberation in June 1944, but bombing is an imprecise matter. The city was shattered.

This presented obstacles to Murphy in locating key landmarks of Van Gogh’s neighbourhood: the cafes, the brothels, even his home, the Yellow House, were wiped from the map. Undeterred, she remapped the city and created a database of people who were his contemporaries and neighbours.

This list grew to 1500. The cafe owner, the butcher, the postman, ladies of the night, a pastor and the doctor — among others — are as compelling as any characters in a 19th-century novel, and they come to life in this book.

Murphy weaves effortlessly between reconstructing Van Gogh’s life in Arles and her own adventures with dusty archives, absent-minded bureaucrats, serendipitous coincidences and labyrinthine dead ends. In the process she lays to rest some long-held assumptions.

For example, he did not drink absinthe, the liquor of choice among many Parisian bohemians of the period, which was thought to cause hallucinations and seizures.

Van Gogh, always sympathetic to the plight of the ailing or destitute, had originally trained as a Protestant pastor and his first post was as a lay minister to miners in Belgium. Alas, his eccentric behaviour found him dismissed after six months. Mental instability was clearly there from the beginning, but the affliction was not confined to him. Of his five siblings, two would commit suicide, two would die in asylums and his brother Theo developed syphilis of the brain. Tellingly, Van Gogh believed that “fragile mental health was a normal part of the creative process rather than an affliction particular to him”.

Painting, which he had embraced as a child, would consume him from the 1880s. His decision to move from the distractions of Paris to the tranquillity of Arles saw him complete 30 paintings in his first two months there. He longed to have a fraternity of fellow artists around him and corresponded at length with Gauguin and others to that end. He said, “You always lose when you’re isolated.”

Gauguin arrived in October 1888 and moved into Van Gogh’s rented Yellow House. Murphy points out that our lives today are so saturated with vibrant colour, it is hard to imagine the shock to the retina of Van Gogh’s palette, especially the sulphurous yellows.

By a forlorn coincidence, in Russia the colour yellow is synonymous with madness and the term for lunatic asylum or psychiatric ward is zholti dom, which means yellow house.

Surprisingly, the crucial information Murphy sought would be among Irving Stone’s papers at the University of California.

Murphy had been corresponding with the library archivist David Kessler, who came across a tiny sketch by the doctor who had treated Van Gogh. Murphy writes, “My adventure started with a simple question: what exactly lay under the bandage? I never imagined I’d actually be able to answer it so conclusively.”

She is determined to pursue the story to the end and recounts in poignant detail Van Gogh’s descent into irreversible instability, the unhappy circumstances of his final incarceration which he knew was a financial burden on his brother Theo — “It makes me very worried when I tell myself that I’ve done so many paintings and drawings without ever selling any” — and his suicide.

Patricia Anderson is an author and editor.

Van Gogh’s Ear: The True Story

By Bernadette Murphy

Penguin, 336pp, $35

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout