Sydney Opera House has a new exhibition lighting its sails

The visually stunning installation, powered by Fondation Cartier, links two vastly different artists in a moving show of country and culture.

Warning: This story features the name of a deceased Aboriginal artist.

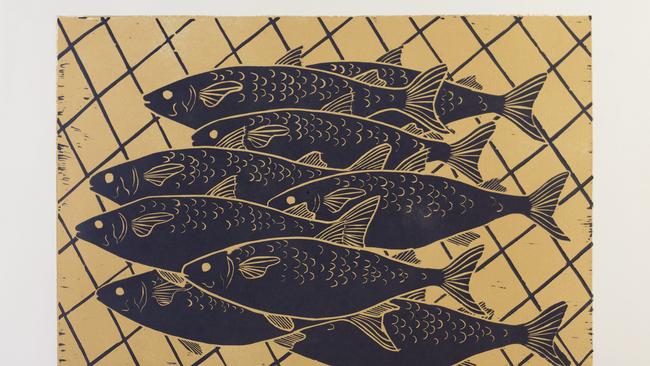

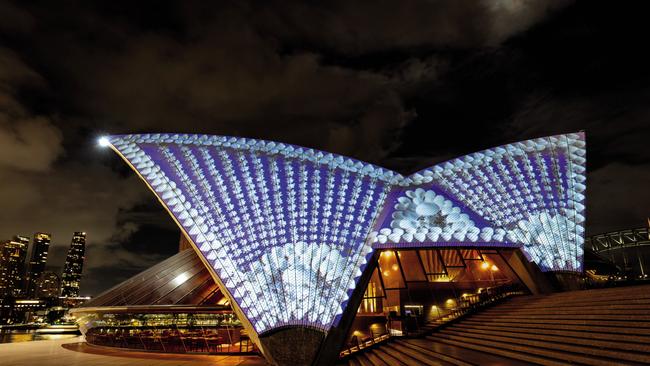

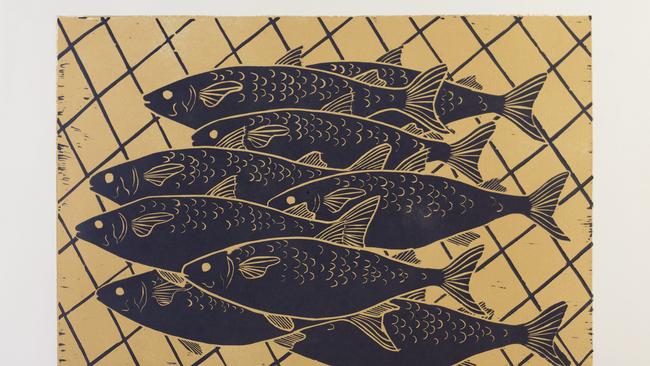

In November, on a cloudless pink evening at Bennelong Point, something was brewing beneath the famous tiled sails of the Sydney Opera House. In the Utzon Room – known for its view that frames Sydney Harbour like a picture – artists Marilyn Russell, Steven Russell and Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami assembled before a crowd of family, friends, admirers and art world milieu. The former pair are the children of Esme Timbery, the late Bidjigal artist and Elder from La Perouse known for her evocations of Australian ephemera and landmarks using shells. Timbery, affectionately known as Aunty Esme, became one of Australia’s best-known First Nations artists before her death in 2023. The latter is one of Brazil’s most revered Indigenous drawers who lives 15,000 kilometres away on Yanomami Indigenous Territory in the Amazon rainforest, and whose shamanistic lineage informs the deep colours and natural wonder of his works. At dusk, Yanomami’s mystical art, alongside Timbery’s, was projected in animated form on the Opera House’s Bennelong sails for the first time as part of a project titled Badu Gili: Healing Spirit (Badu Gili means ‘water light’ in the Gadigal language). The free display will be visible on the Opera House’s eastern Bennelong sails until the end of this year, brought to life by the Fondation Cartier museum and the Biennale of Sydney.

At first, the connection between Timbery and Mokahesi may seem elusive. But for Tony Albert, the Australian artist and Fondation Cartier curatorial fellow who was given the responsibility of selecting the names for Badu Gili, the synergy between the two creatives ran deeper than anticipated.

“When you look at the colonising process that is happening within Brazil, the shrinking of the rainforest and the way that [resembled] the colonial point of contact here in Australia, there is this incredible tangent,” Albert says of pairing an Indigenous Brazilian artist’s work with an Australian First Nations art pioneer. Though she was born in Port Kembla, Timbery lived and worked in La Perouse on Bidjigal country, an area that would eventually be colonised and developed through the evolution of the city of Sydney. But on the peninsula at Botany Bay, she continued the Bidjigal tradition of shellwork, an activity also upheld by her peers and her daughter, Marilyn.

“They’d put the blanket down on the ground and all the shells on the blanket and sort the shells out, and while they were doing that, they were yarning,” says Marilyn, who bonded with her late mother by working on sculptures together.

This relationship between artist and surroundings played a role in Albert’s consulting. When the Opera House was announced as the canvas, Timbery, an artist informed by the beauty of Sydney, came top of mind. “It just wouldn’t have been the right time to go for a desert artist, or a Western Australian or Northern Territory artist,” he says. “This is the time to shine a light on the visibility of First Nations culture here in Sydney.”

The Fondation’s history with Mokahesi stems back to the early days of its work with Indigenous creatives. “[We’ve] been working for 20 years with First Nations artists, mostly from South America and Brazil,” says Hervé Chandès, international director of Fondation Cartier, who’s been working with the institution for two decades and attended the unveiling of Badu Gili. With its support, Mokahesi’s works have journeyed from his rainforest village to be exhibited across the world, shining a light on one of the world’s most remote Indigenous cultures. “I think it is the first time a Yanomami artist is coming to Australia, and it could be the first time an artist from the Amazon is coming and working with First Nations artists from Australia,” Chandès says, adding that the Fondation Cartier intends to continue spotlighting the vast network of Australian First Nations art through its work. “If it’s a commitment, it has to be a long-term project.”

Such projects, Albert notes, are most fruitful when First Nations artists are granted autonomy to work without intervention or direction. “For the Fondation, the idea is just to listen, to hear, to understand, to grow,” he notes. “To hear from a First Nations perspective and viewpoint in Australia, where we get dictated so much on what needs to happen and how we fit within these certain roles, it’s so lovely to work with someone from overseas who has this very different approach, much more in line with the way of thinking is that is actually First Nations artist led.”

On that night back in November, at the end of the formalities, waiters appeared with glasses of port on silver trays; Timbery’s favourite drink. The crowds exited into the now-dark evening, the projections cast onto the Sydney Opera House, illuminating each artist’s still works in motion for the first time.

The gathered audience was full of Timbery’s emotional friends and family. It reminded Marilyn of moments shared with her mother, where she learned that creating art could be a conduit for reflection and lifelong connection. “We call that our healing,” she says. “We were talking, we were yarning and getting closer to one another. That’s what it’s all about.”

Badu Gili: Healing Spirit is on display from sunset at the Sydney Opera House until December 2025.

This story is from the February issue of Vogue Australia, on sale now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout