Xi Jinping’s ‘age of stagnation’ threatens climate, peace, world order

The Chinese economic slowdown is both structural and cyclical, but it’s real and it is the central fact of the global economy right now. It could heighten three global crises.

All geostrategic calculations now must take into account the new Chinese dynamics.

China is enduring an excess of poor-quality investment and a consequent housing oversupply crisis, with a series of giant home-builders unable to pay their debts. It’s suffering deflation in several sectors. Its economic growth this year is forecast at 5 per cent, but hardly anyone in the world any longer believes in official Chinese economic statistics. Youth unemployment is running at well over 20 per cent and is so acutely embarrassing that the central government has decided not to publish the official figure any longer. US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, as a result, urged Beijing to be more honest and open about its economic statistics, as this is important for other economic policymakers and businesses.

Beijing has a recent history of punishing businesses that provide unflattering economic information about China. It has notably declined to publish the Gini coefficient, the measure of income inequality, for 2022. Earlier this month statistics were announced showing a significant decline in Chinese exports as well as a negative figure for inflation in July. Housing prices across most of the country are in sharp decline.

China’s population has already started to decline in absolute numbers. The fertility rate fell last year to a staggeringly low 1.09, having been 1.15 in 2021. This is one of the lowest birthrates in the world. Last year China’s population shrank in absolute terms by about a million. This is a striking example of the Chinese people defying the Communist Party. Beijing has gone from the one-child policy, which it abandoned in the middle of the past decade, to the two-child policy, to the three-child policy. Some provinces have eliminated all restrictions on the number of children a family may have.

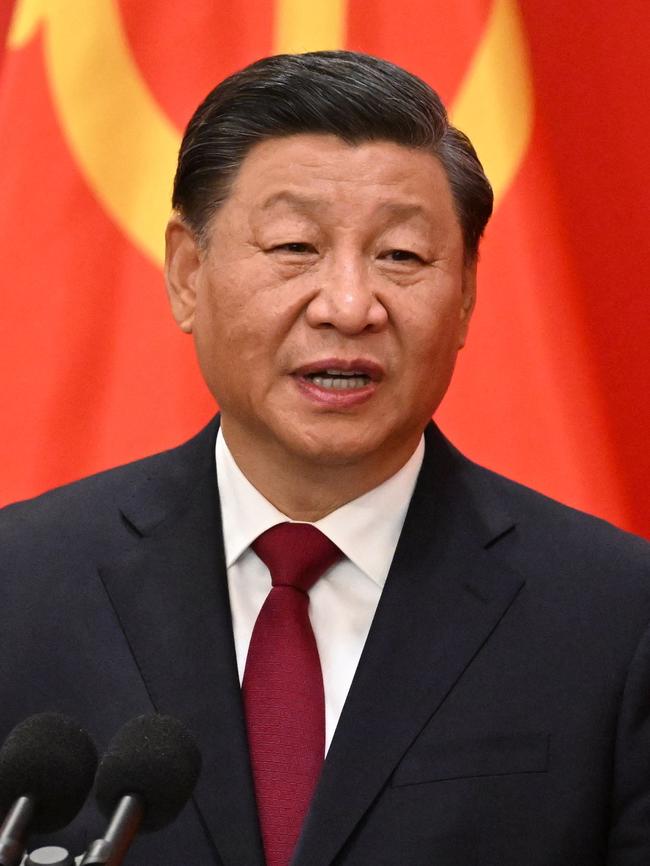

But the Chinese people are not responding. Having children is too expensive. Perhaps, too, people are demoralised by the suffocating control and repression China’s President, Xi Jinping, has gradually increased across the whole of society and the economy. Sinologist Ian Johnson, in a powerful new analysis in the journal Foreign Affairs, calls it Xi’s Age of Stagnation.

Xi acted against China’s IT sector, presumably because he thought it was showing signs of independence from the government; he acted against some of the nation’s highest-profile entrepreneurs, such as Jack Ma, presumably for the same reason. He reasserted the primacy of the Communist Party over the state and over the economy. He reasserted the dominance of state-owned enterprises in the economy.

His government was particularly suspicious of property companies, the after-school tuition industry and the software and entertainment IT types. These were, however, three sectors of the economy that were, until fairly recently, full of life. And they all provide a lot of jobs.

China is still a very wealthy nation, with an economy of more than $US18 trillion ($28 trillion), second only to the US at $US27 trillion. It still clings, absurdly, to an official status as a developing nation.

The slowdown in China could produce a slowdown in Australia, given how much money we make out of selling commodities to China. In fact, so far this year the reverse has been true. In the first half of this year our exports to China soared to more than $100bn. This reflected Beijing lifting most of its trade restrictions on Australia, and also the burgeoning new trade in Australian lithium.

Nonetheless, the Chinese economic slowdown will have big indirect and direct consequences for Australia over time.

How did China get itself into this slowdown? Economist Chris Richardson tells Inquirer it was basically Beijing going all in on the East Asian growth model, over and over and over. The East Asian growth model started with Japan and has been tremendously effective in lifting whole nations out of poverty. It takes the small surplus of savings in an initially rural population – which has to save because there is no welfare at the start of this process – and invests that in low-cost and fairly low-tech manufacturing. It uses the surplus that generates not to finance consumer spending but to move relentlessly up the technology ladder with policies that always favour investment and producers over consumers. Thus producers get low-cost capital, consumers get only modest returns on their savings.

But at some point such economies come up against the middle-income trap and have to make the switch to consumer-led economic growth. That transition is often very hard. Beijing is finding it exceptionally difficult. Some of the shrewdest students of Chinese politics also believe Xi and his colleagues became worried about the political demands a more or less economically independent middle class – with incomes well above $US10,000 – would make.

So Xi’s government reverted to suffocating control that better suits the pro-producer, heavy investment phase of the economic model. As a result it has too much investment, tens of thousands of empty apartments, and unused and uneconomic infrastructure. The same thing happened with China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The BRI financed countless projects that could not get finance otherwise. The reason these projects couldn’t get other finance was because they were mostly unlikely ever to provide an economic return.

So why do I think this slowdown, which is partly cyclical, and therefore temporary, but also partly structural, and therefore permanent, could make Beijing even more difficult in climate change, military matters and challenging the rules-based order? After all, on present indications it’s quite possible the Chinese economy may never overtake the US economy as the world’s biggest. That means the old calculations about US decline and China’s rise may be completely wrong, or at least greatly exaggerated. A China growing more slowly economically and facing absolute demographic decline, on the face of it, means a less powerful China, less able, and perhaps less inclined, to disrupt the international order.

But it could work out quite differently. Quite, quite differently.

Let’s take the crises one by one. The climate, military matters and the rules-based order more generally.

First, on climate, here’s some hot news: there is no such thing as the global green transition, and China is one of the main reasons for this. There is a promise, made by Western leaders, of a green transition away from fossil fuels and to non-carbon sources of energy, but it’s not happening in the real world. At least not yet. The longer I spend in journalism the more inclined I am to privilege what actually happens in the real world as opposed to what is promised by national leaders, policymakers and establishment consensus.

More than once I’ve been seriously upbraided on ABC television for claiming that, far from becoming obsolete, coal is still booming. The situation of coal might change but it certainly hasn’t changed yet.

Global energy use increased last year by more than 2 per cent. Coal, oil and gas made up just on 84 per cent of that energy. That too was an increase on the previous year. More energy, more fossil fuel use, a higher percentage of fossil fuel use. That’s not a global green transition. Greenhouse gas emissions grew 6 per cent in 2021 and 1 per cent last year. China’s greenhouse gas emissions stayed fairly steady in 2022. In non-China Asia, emissions grew by more than 4 per cent last year.

But 2023 is a whole different story. According to a report from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, China’s emissions grew by a staggering 4 per cent in the first quarter of 2023. Even with the slowdown, across the whole of 2023 China will hit a big new record in greenhouse emissions.

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, China accounts for just on 30 per cent of global emissions. That is substantially more than the US and the EU combined. In fact, it is more than the emissions of all developed nations combined. There will come a point in the next decade when China is not only responsible for vastly more emissions than any other nation or group of nations in a year but also responsible for more historic emissions – that is, all the carbon accumulated in the atmosphere since pre-modern times.

No one in the Australian climate debate ever acknowledges this, partly because to do so is just so depressing if you’re a committed climate change activist. In fact, if you really believe in net zero, you just have to look away from China.

Beijing continues to approve new coal-fired power stations at a uniquely fast rate. It has more coal-fired power stations in development than the whole of the US has in any stage of use. The Carbon Tracker website rather politely rates China’s greenhouse performance as “highly insufficient”.

Here’s the big story on greenhouse emissions. Developed nations such as the US, Canada, most of the EU, Japan, Australia and a few others have, at massive cost, substantially reduced their greenhouse gas emissions.

But the carbon story today is overwhelmingly a developing world story. India has now become the world’s third largest greenhouse gas emitter with 7 per cent of the total.

The top 12 nations for greenhouse gas emissions are, in order, China, the US, India, Russia, Japan, Iran, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, South Korea, Canada, Brazil. More than half of those countries will prioritise economic development far ahead of greenhouse gas reduction. China is not committed, even notionally, to reaching even the peak of its greenhouse gas output until 2030, and has a notional commitment to net zero by 2060. India has a similar commitment for 2070.

Let’s get real, just for a minute. Without casting any moral aspersions on anybody, what is there in empirical experience, or mere analytical honesty, that would lead us to give the slightest credence to promises by political leaders for actions in 30 or 40 years?

China is both the biggest producer and the biggest importer of coal. One reason it’s struggling to achieve even its carbon intensity targets – that is, the amount of carbon used per unit of production – is that its domestic coal has low calorific value. This incidentally is a strong environmental argument for Australian coal exports. As luck would have it, Australian coal has high calorific content, so you burn less of it, and produce fewer gases, to produce a given unit of production.

In the very long term, the decline of the Chinese birthrate may help moderate the growth of greenhouse gases. But it is also an observable and nearly universal truth that nations become more environmentally conscious, more willing to pay a price for environmental values, as they grow richer. A China with an economic growth crisis won’t pay much attention to climate change even as it instals vast amounts of renewable energy and seeks to dominate global markets in the manufacture of electric vehicles, solar panels and wind turbines.

None of this implies Australia should abandon efforts to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. Given however that global emissions will keep rising as the developing world keeps developing, it’s less clear that Australia should necessarily bankrupt itself in a race to get all the way to net zero, which is almost certainly an impossible destination anyway.

China is also the engine of military expansion in the world today. As Defence Minister Richard Marles told the recent ALP national conference: “We are witnessing the single biggest conventional build-up in the world since the end of the second world war. In the year 2000, China had six nuclear-powered submarines. By the end of this decade they will have 27. In the year 2000 China had 57 major warships. By the end of this decade they will have 200.” Marles could have added that Beijing is producing nuclear weapons at an unprecedented rate.

Most nuclear weapons states are not increasing their weapons stockpile. A Pentagon report this year said China already had 400 nuclear warheads, is likely to have 700 by 2027, 1000 by 2030 and 1500 by 2035. To be sure, this is fewer nuclear warheads than the US or Russia possesses, but they have both reduced warhead numbers from Cold War highs. Only Beijing is producing new nuclear warheads as fast as it can.

Similarly, Xi frequently tells the People’s Liberation Army to ready itself for battle. According to CIA director William Burns, Xi has instructed the PLA to be ready by 2027 to take Taiwan by force, should Beijing decide it wants to do that.

Slower economic growth could pay into this dynamic in two ways. Beijing could conclude, with a rapidly slowing economy and a declining population, that time is actually not on its side when it comes to taking Taiwan and that it should move sooner rather than later.

Similarly, while the Communist Party rules by ruthless surveillance and coercion, it seeks popular legitimacy on two grounds: rising living standards and ultranationalism.

If rising living standards are absent, the stress may increase on nationalism, especially on the ambition to take Taiwan. That’s not to say Beijing will definitely make such a decision, but it’s a serious possibility.

Chinese militarisation is driving the remilitarisation of the Indo-Pacific, as Russia is driving the remilitarisation of Europe. Japan, in direct response to Beijing’s military build-up, is in the process of doubling its defence budget and could become the third highest military spender in the world.

Even New Zealand, long content to drift, somnolent, in its flakey Middle-earth dreamtime, has decided to re-acquire a military. Australia is one of very few countries that, though well aware of the security situation and talking a good game, is making no move to increase defence spending or acquire meaningful new defence platforms within the next decade.

Finally, the implications of slow growth for Beijing’s participation in the rules-based order.

A long piece in The Washington Post a few days ago detailed how Beijing had sent its police to arrest 77 ethnic Chinese, many young women, living in Fiji. It did this under a policing agreement with the former Fijian government headed by Frank Bainimarama. But the 77 were not subject to any extradition hearings and Fijian police and politicians were shocked at Beijing’s actions. The new Prime Minister, Sitiveni Rabuka, has since suspended the police agreement. Even with such an agreement, however, this cannot be regarded as conduct conforming to international rules and norms.

German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock gave a fascinating speech via Zoom to the Lowy Institute in Sydney. She represents the Green Party in the German parliament and governing coalition. But the German Greens, in touch with strategic reality, bear no resemblance at all to the Australian Greens.

In the speech, Baerbock praised Australia for resisting Beijing’s economic coercion. Her government recently published a new national China strategy that seeks constructive engagement where possible but also faces up to the reality of modern China under Communist Party rule. She said: “Increasingly, China is a rival when it comes to the very fundamentals of how we live together in this world: the principles of our international order and respect for human rights.”

Though more tough-minded than most of her ministerial colleagues, Baerbock represents the growing European view of China.

Former prime minister Kevin Rudd, who is a brilliant analyst of China, in a recent speech in Singapore commented that we can no longer regard China as a status quo power. It is now heavily revisionist. This is true not only of Beijing’s geostrategic aims but also its methodology. And if it was ruthless about the international system when things were going well, it’s likely to be doubly so now amid economic and demographic troubles.

Nothing here is foreordained. And of course Beijing is not mounting the full frontal assault on international order that Russia is with its brutal war in Ukraine.

But no one should think for a moment that even if the Albanese government is entirely successful in stabilising Canberra’s relationship with Beijing, that we, and the world, do not face fundamental challenges arising out of Chinese power, now newly and unpredictably complicated by the new turn in the Chinese economy.

The Chinese economic slowdown is both structural and cyclical, but it’s real and it is the central fact of the global economy right now. It could heighten three global crises that China is the centre of: climate change; the danger of military conflict evident in military weapons growth, nuclear weapons growth and cross-border military tensions; and the gradual erosion of the rules-based international order more generally.