China’s 40-year boom is over: so what comes next?

Now the model is broken.

What worked when China was playing catch-up makes less sense now that the country is drowning in debt and running out of things to build. Parts of China are saddled with underused bridges and airports. Millions of apartments are unoccupied. Returns on investment have sharply declined.

Signs of trouble extend beyond China’s dismal economic data to distant provinces, including Yunnan in the southwest, which recently said it would spend millions of dollars to build a new Covid-19 quarantine facility, nearly the size of three football fields, despite China having ended its “zero-Covid” policy months ago, and long after the world moved on from the pandemic.

Other localities are doing the same. With private investment weak and exports flagging, officials say they have little choice but to keep borrowing and building to stimulate their economies.

Economists now believe China is entering an era of much slower growth, made worse by unfavourable demographics and a widening divide with the US and its allies, which is jeopardising foreign investment and trade. Rather than just a period of economic weakness, this could be the dimming of a long era.

“We’re witnessing a gearshift in what has been the most dramatic trajectory in economic history,” said Adam Tooze, a Columbia University history professor who specialises in economic crises.

What will the future look like? The International Monetary Fund puts China’s GDP growth at below 4 per cent in the coming years, less than half of its tally for most of the past four decades. Capital Economics, a London-based research firm, figures China’s trend growth has slowed to 3 per cent from 5 per cent in 2019, and will fall to around 2 per cent in 2030.

At those rates, China would fail to meet the objective set by President Xi Jinping in 2020 of doubling the economy’s size by 2035. That would make it harder for China to graduate from the ranks of middle-income emerging markets and could mean that China never overtakes the US as the world’s largest economy, its longstanding ambition.

Many previous predictions of China’s economic undoing have missed the mark. China’s burgeoning electric-vehicle and renewable energy industries are reminders of its capacity to dominate markets. Tensions with the US could galvanise China to accelerate innovations in technologies such as artificial intelligence and semiconductors, unlocking new avenues of growth. And Beijing still has levers to pull to stimulate growth if it chooses, such as by expanding fiscal spending.

Even so, economists widely believe that China has entered a more challenging period, in which previous methods of boosting growth yield diminishing returns.

Some of these strains were apparent before the pandemic. Beijing was able to keep growth ticking over by borrowing more and relying on a booming housing market, which in some years accounted for more than 25 per cent of China’s gross domestic product.

The country’s initial success in containing Covid-19, and a surge in pandemic spending by US consumers, further masked China’s economic troubles. The housing bubble has since popped, Western demand for Chinese products has ebbed and borrowing has reached unsustainable levels.

The outlook has darkened considerably in recent months. Manufacturing activity has contracted, exports have declined, and youth unemployment has reached record highs. One of the country’s largest surviving property developers, Country Garden Holdings, is on the cusp of a possible default as the overall economy slips into deflation.

Japan-like slowdown?

Without more aggressive stimulus from Beijing, and meaningful efforts to revive private sector risk-taking, some economists believe China’s slowdown could snowball into prolonged stagnation akin to what Japan has experienced since the 1990s, when the bursting of its real-estate bubble led to years of deflation and limited growth.

Unlike Japan, however, China would be entering such a period before reaching rich-world status, with per capita incomes far below more advanced economies. China’s national income per person reached about $12,850 last year, below the current threshold of $13,845 that the World Bank classifies as the minimum for a “high-income” country. Japan’s per capita national income in 2022 was about $42,440, and the US’s was about $76,400.

A weaker Chinese economy could also undermine popular support for Xi, the most powerful Chinese leader in recent decades, though there is no current indication of organised opposition. Some US analysts worry Beijing could respond to slower growth by becoming more repressive at home and more aggressive abroad, raising the risks of conflict, including potentially over the self-governing island of Taiwan.

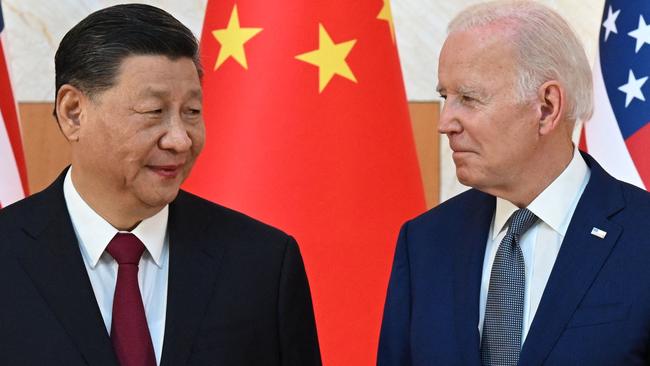

At an Aug. 10 political fundraiser, President Biden called China’s economic problems a “ticking time bomb” which could spur its leaders to “do bad things.” Beijing fired back with a commentary by its official Xinhua News Agency, saying Biden “intends to take smearing China as part of his ‘grand strategy’ to shoot America’s economic troubles.”

The commentary also described China’s economic recovery this year as robust, despite some challenges.

Chinese officials have taken some modest steps to revive growth, including cutting interest rates, and have pledged to do more if conditions worsen. The State Council Information Office, which handles media inquiries for China’s leadership, didn’t respond to questions.

“Certain Western politicians and media have exaggerated and hyped up the current difficulties in China’s post-Covid economic recovery,” a Foreign Ministry spokesman said on Aug. 16. “Facts will prove them wrong.”

The transition marks a stunning change. China consistently defied economic cycles in the four decades since Deng Xiaoping started an era of “reform and opening” in 1978, embracing market forces and opening China to the West, in particular through international trade and investment.

During that period, China increased per capita income 25-fold and lifted more than 800 million Chinese people out of poverty, according to the World Bank – more than 70 per cent of the total poverty reduction in the world. China evolved from a nation racked by famine into the world’s second-largest economy, and America’s greatest competitor for leadership.

Academics were so enthralled by China’s rise that some referred to a “Chinese Century,” with China dominating the world economy and politics, similar to how the 20th century was known as the “American Century.” China’s boom was underpinned by unusually high levels of domestic investment in infrastructure and other hard assets, which accounted for about 44 per cent of GDP each year on average between 2008 and 2021. That compared with a global average of 25 per cent and around 20 per cent in the US, according to World Bank data.

Such heavy spending was made possible in part by a system of “financial repression” in which state banks set deposit rates low, which meant they could raise funds inexpensively and fund building projects. China added tens of thousands of miles of highways, hundreds of airports, and the world’s largest network of high-speed trains.

Over time, however, evidence of overbuilding became apparent. About one-fifth of apartments in urban China, or at least 130 million units, were estimated to be unoccupied in 2018, the latest data available, according to a study by China’s Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.

A high-speed rail station in Danzhou, a city in China’s southern province of Hainan, cost $5.5 million to build but was never put into use because passenger demand was so low, according to Chinese media reports. The Hainan government said keeping the station open would incur “massive losses.” Efforts to reach the local government were unsuccessful.

Guizhou, one of the poorest provinces in the country with GDP per capita of less than $7,200 last year, boasts more than 1,700 bridges and 11 airports, more than the total number of airports in China’s top four cities. The province had an estimated $388 billion in outstanding debt at the end of 2022, and in April had to ask for aid from the central government to shore up its finances.

Kenneth Rogoff, a professor of economics at Harvard University, said China’s economic ascent draws parallels to what many other Asian economies went through during their periods of rapid urbanisation, as well as what European countries such as Germany experienced after World War II, when major investments in infrastructure boosted growth.

At the same time, decades of overbuilding in China resembles Japan’s infrastructure construction boom in the late 1980s and 1990s, which led to overinvestment.

“The leading point is they are running into diminishing returns in building stuff,” he said, “There are limits to how far you can go with it.” With so many needs met, economists estimate China now has to invest about $9 to produce each dollar of GDP growth, up from less than $5 a decade ago, and a little over $3 in the 1990s.

Returns on assets by private firms have declined to 3.9 per cent from 9.3 per cent five years ago, according to Bert Hofman, head of the National University of Singapore’s East Asian Institute. State companies’ returns have retreated to 2.8 per cent from 4.3 per cent.

China’s labour force, meanwhile, is shrinking, and productivity growth is slowing. From the 1980s to the early 2000s, productivity gains contributed about a third of China’s GDP growth, Hofman’s analysis shows. That ratio has declined to less than one sixth in the past decade.

Deepening debt

The solution for many parts of the country has been to keep borrowing and building. Total debt, including that held by various levels of government and state-owned companies, climbed to nearly 300 per cent of China’s GDP as of 2022, surpassing US levels and up from less than 200 per cent in 2012, according to Bank for International Settlements data.

Much of the debt was incurred by cities. Limited by Beijing in their ability to borrow directly to fund projects, they turned to off-balance sheet financing vehicles whose debts are expected to reach more than $9 trillion this year, according to the IMF.

Rhodium Group, a New York-based economic research firm, estimates that only about 20 per cent of financing firms used by local governments to fund projects have enough cash reserves to meet their short-term debt obligations, including bonds owned by domestic and foreign investors.

In Yunnan, location of the giant quarantine centre, heavy infrastructure spending lifted growth for years. Officials spent hundreds of billions of dollars including on Asia’s tallest suspension bridge, more than 6,000 miles of expressways and more airports than many other regions in China.

The projects boosted tourism and helped expand trade of Yunnan products including tobacco, machinery and metals. From 2015 to 2020, Yunnan was one of the fastest-growing regions in China. Growth has weakened in the past few years. The slumping property market has hit local finances hard, as revenue from land sales dries up.

Yunnan’s debt-to-revenue ratio climbed to 151 per cent in 2021, breaching a 150 per cent level designated as alarming by the IMF, and up from 108 per cent in 2019, according to Lianhe Ratings, a Chinese rating agency. Fitch Ratings earlier this year said financing firms used by the province to fund infrastructure construction were risky because of the size of their borrowings and the government’s strained finances.

Yet Yunnan has continued to hatch big schemes. In early 2020, the Yunnan government said it planned to spend nearly $500 billion on hundreds of infrastructure projects, including a more than $15 billion program aimed at diverting water from parts of the Yangtze River to the dry centre of the province.

A February plan issued by Wenshan, a city in Yunnan, listed the “permanent” quarantine centre as one of several measures aimed at promoting economic stability. Once the government officially put out a bid in June for its construction, local residents questioned the use of funds.

“It’s such a waste of money,” wrote one user of Weibo, a popular microblogging platform in China.

A Yunnan official confirmed the plan to build the quarantine facility, which is expected to be completed at the end of this year, but declined to comment further.

In Beijing’s corridors of power, senior officials have recognised that the growth model of past decades has reached its limits. In a blunt speech to a new generation of party leaders last year, Xi took aim at officials for relying on borrowing for construction to expand economic activities.

“Some people believe that development means investing in projects and scaling up investments,” he said, while warning, “you can’t walk the old path with new shoes.” Xi and his team so far have done little to shift away from the country’s old growth model.

The most obvious solution, economists say, would be for China to shift toward promoting consumer spending and service industries, which would help create a more balanced economy that more resembles those of the US and Western Europe. Household consumption makes up only about 38 per cent of GDP in China, relatively unchanged in recent years, compared with around 68 per cent in the US, according to the World Bank.

Changing that would require China’s government to undertake measures aimed at encouraging people to spend more and save less. That could include expanding China’s relatively meagre social safety net with greater health and unemployment benefits.

Xi and some of his lieutenants remain suspicious of US-style consumption, which they see as wasteful at a time when China’s focus should be on bolstering its industrial capabilities and girding for potential conflict with the West, people with knowledge of Beijing’s decision-making say.

The leadership also worries that empowering individuals to make more decisions over how they spend their money could undermine state authority, without generating the kind of growth Beijing desires.

A plan announced in late July to promote consumption was criticised by economists both in and outside China for lacking details. It suggested promoting sports and cultural events, and pushed for building more convenience stores in rural areas.

Instead, guided by a desire to strengthen political control, Xi’s leadership has doubled down on state intervention to make China an even bigger industrial power, strong in government-favoured industries such as semiconductors, EVs and AI.

While foreign experts don’t doubt China can make headway in these areas, they alone aren’t enough to lift up the entire economy or create enough jobs for the millions of college graduates entering the workforce, economists say.

Beijing has spent billions of dollars to try to build up the country’s semiconductor industry and reduce its dependence on the West. That has resulted in expanded production of less-sophisticated chips, but not the advanced semiconductors produced by companies such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing. Among the projects that failed were two high-profile foundries that received hundreds of millions of dollars in government support.

Last week, just as Beijing released a barrage of disappointing economic data, the party’s premier journal, Qiushi, published a speech made by Xi six months earlier to senior officials, in which the leader emphasised the importance of focusing on long-term goals instead of pursuing Western-style material wealth. “We must maintain historic patience and insist on making steady, step-by-step progress,” Xi said in the speech.

Dow Jones

For decades, China powered its economy by investing in factories, skyscrapers and roads. The model sparked an extraordinary period of growth that lifted China out of poverty and turned it into a global giant whose export prowess washed across the globe.