Xi Jinping’s high stakes economic gamble has the Australian government on edge

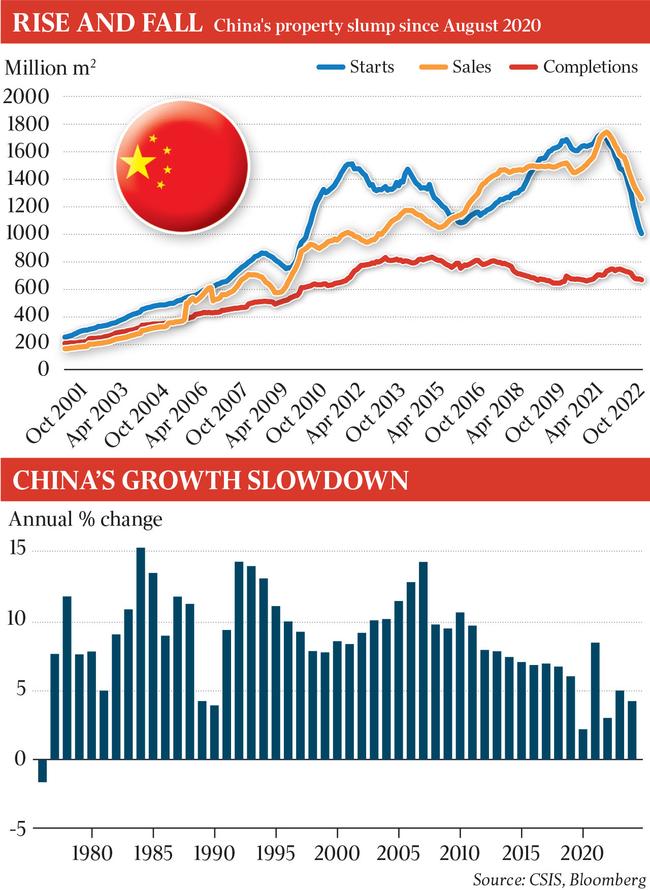

No other government has ever tried to prick an economic bubble of the size Beijing has its sights on. Australia has a new China problem: we have a huge stake in its success - or failure.

Canberra has a new China problem.

Six months ago, Communist Party officials were promising to use “full firepower” to ignite the Chinese economy. “For a three-year project, aim for two years,” the party secretary of Guangdong province, China’s economic engine, instructed officials and business leaders back then.

It sounded like another whopping stimulus package was on the way: more airports, more fast-train lines, more hulking structures, and all full of iron ore from Australia’s biggest taxpayers – BHP, Rio Tinto and Fortescue.

Those expectations are now dashed. Despite a raft of bad economic indicators, President Xi Jinping and his economic advisers seem to be determined to grind through the pain.

It’s part of an unprecedented attempt to reign in China’s rapacious property developers, the motor of a 40-year economic boom that has benefited Australia more than perhaps any country in the world.

The stakes are huge, far overshadowing the impact of China’s $20bn economic coercion campaign on Australia, which has now mostly been unwound.

Almost a quarter of China’s GDP comes from property. Real estate accounts for nearly 70 per cent of China’s household wealth.

“No other government had ever undertaken a similar pre-emptive move against a bubble of comparable scale,” says Adam Tooze, an expert on economic crises at Columbia University.

Mr Xi embarked on this monumental task in August 2020, when his “Covid zero” policy had made China’s economy the envy of the world. China was the only major economy to grow in the pandemic’s first year.

Beijing’s attempt to de-risk its bloated property sector was not front of mind for most Australians three years ago. Now it is making headlines around the world. The news keeps getting worse.

Last week, Evergrande Group, the world’s most heavily indebted property developer, filed for bankruptcy protection in a US court. Fellow Chinese property giant Country Garden is on the brink of default.

No wonder Jim Chalmers has former Macquarie Group chief Nicholas Moore working on a strategy to better position the economy towards Southeast Asia.

“The global economy is really this tug of war right now between resilience and risk,” the Treasurer said on Wednesday.

“On the resilience side, the American economy has held up especially well. The banking system has held up better than many expected. Inflation is moderating. But the softening of the Chinese economy, I think, is one of the risks that certainly we’re most attentive to and that the global economy is watching most closely,” Dr Chalmers said.

The ‘Four Ds’

China’s economy is a long way from bust. Even with downgrades, the world’s second biggest economy is forecast to grow by almost 5 per cent this year.

The IMF projects China will contribute almost one third of total world growth in 2023 — more than any other country.

But international investors are increasingly nervous. Foreign direct investment in China plunged by 87 per cent in the three months to July, according to figures released by Beijing last week.

Logan Wright, director of China markets research at Rhodium Group, thinks the extent of China’s economic weakness is still “widely underappreciated”. He told the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission that the downturn would have historic consequences.

“Beijing is no longer an economic pacing threat or likely to overtake the United States in any significant measure of power in the next two decades,” he told a hearing in Washington.

“Beijing will never be able to make a credible claim to global economic primacy.”

The economic problems go beyond the debt-laden property sector.

ASX listed infant formula company A2 Milk’s share price dived more than 13.6 per cent on Monday after it warned China’s longer-term birthrate was “inherently uncertain”. Last year, China’s population started declining, years earlier than previously forecast following the ongoing collapse of its birthrate.

Zongyuan Zoe Liu, the Maurice R. Greenberg Fellow for China Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, lists “Four Ds” that drag on China’s growth: demand, debt, demographics and decoupling.

Each is a source of concern in Australian boardrooms. Each poses a thorny policy challenge for Mr Xi, the “Chairman of Everything”.

Many of China’s 1.4 billion people are adjusting their expectations for their working lives.

Zhu Quanlin, 36, was laid off last year from “a big company” where he was a sales manager. Mr Zhu says he wasn’t worried when he was laid off. He thought his experience would allow him to find a similar position with a similar salary.

“I was wrong,” he said. “It was not really a problem with me, but a problem with the economy. People are simply not buying, so there is no need for ‘sales managers’.”

After almost a year out of work, Mr Zhu dropped his expectations. He is now working as a fast-food courier. “When you have a family to support, there are not many choices you can make,” he said.

Pockets booming

China’s government appears rattled about rising unemployment. Last week, Beijing’s National Bureau of Statistics announced it would no longer release its youth unemployment rate.

The decision was widely mocked on China’s internet. “As long as I don’t announce it, then nobody is unemployed,” wrote one social media user.

Pockets of China’s economy are booming. American coffee chain Starbucks’ sales in China grew by 46 per cent in the last quarter, a striking example of the rebound in consumer spending after the end of Covid restrictions.

Domestic tourism has roared back. Spots within China that have international influences are particularly popular.

Mr Xi’s government has also continued investing huge sums into electric vehicles, batteries, and solar and wind power.

In the first half of the year China overtook Japan as the world’s top car exporter. That has been great news for Australia’s lithium industry, which barely existed a few years ago. Australia’s lithium exports to China reached $11.7bn in the first half of the year, up from a paltry $470m two years ago.

The industry has just overtaken liquefied natural gas as Australia’s second biggest export to China, trailing only iron ore. BHP forecasts it will continue to send the majority of its iron ore to China for years to come, even with the housing slump. Iron ore exports to India and Southeast Asia are forecast to grow faster but they remain a fraction of sales to China.

There are other bright prospects for Australian companies. China’s greying population is bad news for A2 and fellow listed infant formula business Bubs, but it is promising for Lendlease. The ASX-listed property giant opened its first retirement village in Shanghai in 2021.

Hearing aid maker Cochlear is also well positioned to benefit from the world’s biggest pool of retirees. During the pandemic, it opened a new factory in Chengdu, an investment that fits in well with Beijing’s policy to develop China’s west.

Overconfidence, hubris

Mr Xi has put officials on notice: he wants China’s old, investment heavy economic model cast aside.

“Most cadres can actively adapt to the new development requirements, but some cadres cannot keep up,” Mr Xi said in remarks released in July.

“Some think that development is about launching projects, doing investments, and expanding scale,” he said.

While Xi scolds his officials, some international observers finger his decision making as the source of China’s current economic dilemma.

Analysts have long advised Beijing to address its ballooning real estate sector – but many question if the middle of a huge international economic shock was the right moment to tackle China’s investment-heavy growth model.

Even more question the wisdom of a crackdown of China’s best known business figure, Jack Ma.

Professor Tooze, the historian of economic crises, suspects “overconfidence and hubris” following the initial success of his Covid zero policy led China’s leader to embark his attempt to reign in his country’s huge property sector.

“China’s current crisis cannot be understood unless we also allow for the role of overconfidence, risk-taking and, possibly, miscalculation on the part of a regime facing an unprecedented array of challenges,” he writes in an essay published this week.

Whatever state of mind Mr Xi was in when he began, Canberra hopes he has a plan for how this ends.

Additional reporting: Noah Yim

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout