50 years since the Vietnam War ended, myths persist about Canberra’s role

Australian participation was a cynical exercise by government to build up an insurance policy.

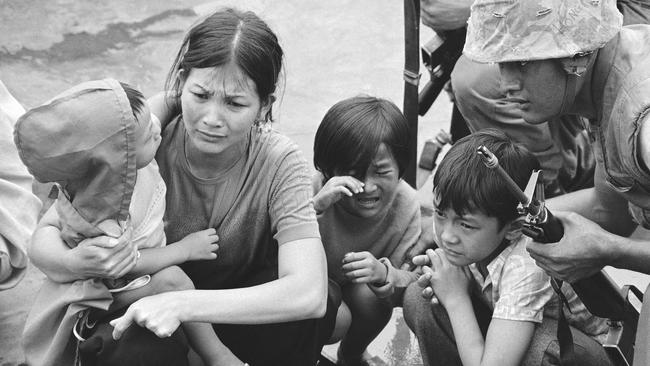

This year is the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. It was on April 30, 1975, when North Vietnamese tanks smashed through the gates of South Vietnam’s presidential palace, ending a conflict that had lasted three decades from the end of World War II.

This was the final act of the war but despite, or perhaps because of, the fact it is recent history, Australia’s participation in the conflict has been the subject of persistent myths across the past half-century.

One myth, still repeated on occasion, is that the Whitlam government withdrew Australia’s troops on its election in December 1972. In fact the troop commitment, which had been announced in April 1965 by the Menzies government, had been withdrawn by the end of 1971 under the McMahon government.

At one time a second myth suggested that the Johnson administration in Washington had successfully pressured the Australian government to commit ground troops to the conflict. As it happened, Canberra was desperate to be involved in the war.

In early January 1965 Paul Hasluck, then external affairs minister, complained to the head of his department that he was “gravely concerned” at the hesitancy of the Americans in escalating the conflict and urged the use of arguments that would “reinforce the persuasions of any like-minded elements within the United States administration”.

The one thing that particularly concerned Hasluck was that there might be some form of settlement of the fighting, adding: “I fear above all the likelihood of slipping into negotiation by default.”

The prospect of negotiations had been raised by French president Charles de Gaulle and the British government but this was not what the Australian government wanted. When the war finally proved unwinnable on the part of the US and its allies, another myth surfaced to argue that no one could have foreseen this outcome in 1965. Even in the Johnson administration, however, there were those who predicted what ultimately would happen and, as early as May 1961, de Gaulle had said to Lyndon Johnson’s predecessor as US president, John Kennedy: “You will, step by step, become sucked into a bottomless military and political quagmire despite the losses and expenditure that you may squander.”

Yet another myth, still prevalent in some quarters, is that Australian troops were the subject of abuse and, in some cases, physical attack when they returned home from Vietnam. There has never been any evidence of this but it is true that many of those who went to Vietnam feel their role has never been properly recognised.

This feeling may be close to the truth but it is in many ways a natural consequence of the fact the war was lost and it was the first conflict in which Australia had been involved that did not have the support of the entire community so that those returning would never be viewed as heroes like their predecessors in earlier wars.

On the subject of community support, it sometimes seems to be assumed today that the war was always unpopular in Australian society. But polls in December 1968 still showed almost half of all voters believed Australia should stay in Vietnam while just over a third wanted the troops withdrawn. This was at a time when it might be thought that it had become obvious that the war could not be won and when the debate in the US on its continuation had become highly charged. This was not the Australian electorate’s finest hour. The polls did change gradually over the next few years but only as the position of the US and its allies continued to deteriorate.

One other myth that might be drawn from some accounts of the period is that universities at least were hotbeds of radicalism and did not reflect the views of the electorate as a whole. In fact only a small minority of university students had any real interest in politics and only some of those were actively opposed to the war. In contrast to many of their counterparts in the US, Australian universities at this time did largely reflect the views of society as a whole.

All in all, Vietnam is a sad chapter in modern Australian history. A cynical government, supported by an unthinking electorate, invited itself to a conflict in which more than 500 Australians died and many more were seriously wounded.

This was a cynical exercise because the Australian government did not really care whether the war was won or lost or what damage it did to America’s international reputation and domestic politics.

Its goal was to build up an insurance policy with the US but, as we have seen recently, no insurance policy lasts forever.

There is no doubt that Robert Menzies was a very talented politician and his name is often evoked by contemporary Liberals, but few of these mention his responsibility for Australia’s participation in one of the most futile conflicts of modern times.

Michael Sexton is the author of War for the Asking: How Australia Invited Itself to Vietnam (New Holland, 2002).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout