West under strain as traumas escalate in an age of polycrisis

The past year has seen multiple shocks, internal and external, to democratic societies and the world order | WATCH Paul Kelly on the year that was.

Western democracies, divided within, battled to meet new and ancient challenges.

In Australia the freshly minted Albanese government, elected only in May 2022, began to look unexpectedly weary and uncertain, having expended excessive political capital on a uniquely Australian flawed project – the constitutional voice for the Indigenous people. The lesson was a public revolt against being patronised by the elites.

With the emergence of artificial intelligence the existential question for civilisation was posed in 2023: will the technological revolution deliver a better world or destroy our social order? Technology offers a potentially transformed economy with greater prosperity yet the unprecedented risk is that the human race is developing machines smarter than ourselves.

Australia has become part of the great 21st-century experiment: can Western democracies succeed in an age of polycrisis? Leadership loomed as a generic problem across most of the West as governments and public policy faltered before a range of economic, climate and strategic problems. Opportunities abound in the swiftly moving 2020s decade yet the real lesson from 2023 is the sheer scale of the task ahead.

There is a great unwinding under way: free markets, globalisation and economic interdependence – the jewels of the late 20th century – are in retreat. The international order is fragmenting. Nationalism, tribalism and authoritarianism are on the march, offering a bizarre contrast to the notion that humanity is likely to rise or fall together in the coming century.

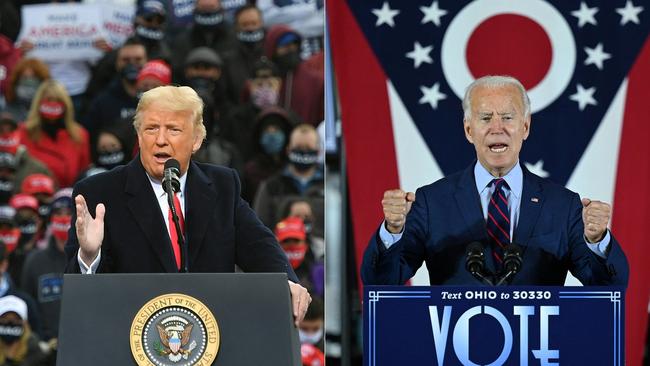

Much of the world is still made in America. Financial Times, London chief economics commentator Martin Wolf reminded us this year that “when the US talks, the world listens” and “whether we like it or not, we all live in the world that the US has made”. Yet a shadow hangs over that world. The year 2023 throws up the conundrum about the US: how can such a dynamic country be reduced to a presidential contest between an age-impaired Joe Biden and a destructive narcissist, Donald Trump?

Yet US leadership is critical in this phase of history. Australia under both the former Morrison government and now the Albanese government is deepening its security ties with the US, notably through the AUKUS agreement – a statement of belief in America.

US analyst Fareed Zakaria said that with wars in Ukraine and the Middle East and China’s challenge to the global order, “if America retreats, in each of these three areas, aggression and disorder will rise”.

Epic security and civilisation issues dominate. The military conflict over Ukraine will determine the credibility of US and European power and whether Russia’s aggression will be rewarded; the Israel-Hamas war means the Middle East hovers at an inflection point, either a deepening polarisation on both sides or, somehow, a push to resurrect the two-state, Israel and Palestine, political solution; and the supreme strategic question remains – whether the competition between the US and China can be contained short of a military conflict over Taiwan. The 2023 irony, on full display, is the flawed nature of the two superpowers, the US engulfed in political trauma and China, pumped up for overreach, yet blighted by serious economic and financial strains.

At home Australia talks endlessly about the world’s problems but is far less effective in terms of action. Labor is still sorting how it functions in the 2020s. It is big on diplomacy, champions climate action, wants to be everybody’s friend, can’t devise a tenable program for long-run private investment, talks a modern agenda on technology but runs a backwards agenda on industrial relations.

Labor is a culturally progressive party caught in an age dominated by power, patriotism and economic competition, its vulnerability is the progressive mantra of identity politics, group rights and scepticism towards Western liberalism.

Facing structural challenges in the rise of China, weak productivity, stagnant living standards and the need for economic renewal, Australia’s mindset is too introspective, suggesting a lack in national self-confidence and chronic disagreement about policies for the future.

The ambition of Jim Chalmers is tantamount to remaking the economy – becoming a renewable energy superpower, exploiting the assets of the digital age, utilising the rise of the care economy – the problem, however, is the gap between aspiration and delivery.

Australia was a divided nation in 2023. The referendum on the voice dominated the year’s politics with Anthony Albanese enduring a humiliating defeat 61-39 per cent and only 32 electorates out of 151 voting for his proposal. The campaign saw an unprecedented split in modern Australia.

Elite power and social conscience for the Yes case were on display from corporations, business leaders, philanthropists, universities, celebrities, trade unions, community leaders, public media, remote Indigenous communities, the affluent suburbs and the inner cities while the No vote came from the outer suburbs, the regions, the rural areas, Coalition-held seats, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia – and reflected both a revolt against and an indifference towards elite lecturing and progressive sophistry.

The Prime Minister’s 2023 odyssey was extraordinary and alarming – a giddy slide from ascendancy to a world of tribulation. At year’s end his government looks unconvincing. It is plagued by high interest rates, cost-of-living pressures, a per capita income recession, housing unaffordability, high power prices and a range of security dilemmas.

Worst of all, the government seems to lack central policy co-ordination behind a robust agenda as ministers run their own, often contradictory, policy programs. From early 2024 the government needs to have broken the irresolution that marks the end of 2023. Albanese said he wanted to govern like Bob Hawke, but there is little resemblance to Hawke in this outfit.

The year 2023 was when politics became competitive again. The most recent Newspolls have the Albanese government and Peter Dutton-led Coalition tied 50-50 in two-party-preferred terms last month and with Labor holding a 52-48 per cent lead in December. The Coalition still suffers from the structural problem of the last election when it lost its prized blue-ribbon seats to the teals.

Labor’s problem only disguises the still unresolved dilemma for the Liberal Party: how does it intend to rebrand its policies and its image for the next election?

The grave risk for Albanese – at this point – is not losing the next election but being reduced to the doom of minority government. There is no silver bullet available to meet the global challenge of the 2020s decade.

The danger is that it will turn into a travail of regional war, great power rivalry, climate upheaval, population movements, technological disruption and growing inequality.

Columbia University’s Adam Tooze, who has popularised the term polycrisis, an idea that began with French theorist Edgar Morin, said: “The polycrisis term has a real utility descriptively, because it’s arm-waving. It’s going, ‘Look, there’s a lot of stuff happening here all at once.’ And that precisely is what we’re trying to wrap our minds around.”

Writing in the Financial Times last year, Tooze said: “The pace of change is staggering … Today the world is organised for the most part into powerful states that have gone a long way towards abolishing absolute poverty, generates total global domestic product of $90 trillion and maintains a combined arsenal of 12,705 nuclear weapons, while depleting the carbon budget at the rate of 35 billion metric tonnes of CO2 a year. To imagine that our future problems will be those of 50 years ago is to fail to grasp the speed and scale of historical transformation … The more successful we are at coping the more tension builds. If you have found the past few years stressful and disorientating, if your life has already been disrupted, it is time to brace. Our tightrope walk with no end is only going to become more precarious and nerve racking.”

Here is the doorway to another story of the times – the obsession about individual fulfilment. It comes in the form of campaigns for individual and group rights, personal renewal, the quest for a meaningful life. The transformation of left-wing politics is stunning – from class war to individual self-expression, witness the many dimensions in terms of rights around sex, gender and race. Some people search for a secular faith; others look to family for a deeper sense of meaning; even others elevate personal feelings as the touchstone of their lives.

The truth of the age is that politics is downstream of culture. The year 2023 saw a deepening of the clash over values with varying manifestations: traditional Australians value faith, flag, family, national unity and personal responsibility while elites and progressives prioritise diversity and inclusion, campaigns against racial, sexual and gender discrimination, are cosmopolitan in outlook, pro-immigration, pro-renewables and sceptical of national security overreach. The transcendent moral warning remains that of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks: “When there is no shared morality, there is no society.” Debates about the breakdown of trust – more prevalent than ever in 2023 – are mainly useless because they ignore the main cause: when society cannot agree on core values there is no trust.

The evolving culture of the West is based on feelings; one’s feelings must be honoured. Rooted in narcissism, the sentiment is “being true to myself”. This is the new morality. Australia’s mainstream and social media in 2023 was saturated with celebrations of people being true to themselves.

US writer Yuval Levin said of the self-expressive culture: “We are naturally inclined to recoil from any demands that we conform to the requirement of some external moral standard – a set of rules that keeps ‘me’ from being ‘the real me’.”

Inside their homes parents are locked in a silent, frightening, unprecedented battle with their young children who, once addicted to their devices and phones, cannot live without them and refuse to surrender them. It is a new form of intimate social warfare; the revolt of the technologically addicted youth generation.

In 2023 US social psychologist Jonathan Haidt warned that the West was witnessing “the great re-wiring of childhood”, which meant the central experience of childhood had become “phone based” not “play based”. Based on his survey work Haidt said the great change came across the Anglosphere from about 2012 when rates of mental illness and suicide exploded, most pronounced where young people were less integrated into society and religious communities. The onus lies on parents, schools and authorities to address this crisis. This represents an extreme form of the wider generational tension at work.

Anxiety in Australia over escalating housing prices has become a tangible factor in family financial arrangements, social policy, the equity debate and economic measures to produce a housing price correction. In truth, the answers will be long term. They will require sacrifices from the asset-rich baby boomers to the wage-poor, home ownership poor, under-30s generation. If 2023 saw peak alarm at this generational divide, it fell far short of finding and implementing the answers.

Labor is now at a pivotal point in its history – Albanese needs to show after the Rudd-Gillard failures that the party can deliver on economic management, national security and climate change policy – the conditions for sound Australian government. At the end of 2023 the Treasurer offered the outlook for the future – inflation to fall to 3.75 per cent by mid-2024, the extent of rising unemployment to be contained below 4.5 per cent, a soft landing for the economy after the Reserve Bank’s dramatic hikes in the cash rate, hopes that the current cash rate of 4.35 per cent might represent the peak of the cycle and wages now rising ahead of prices to deliver real wage gains.

All being well, it is a story of gradual progress. Yet Chalmers is dealing with an impatient electorate, less forgiving than before, restless after the Covid pandemic, more focused on personal and financial security, aspirational yet also looking to government for support, benefits and effective service delivery.

The dilemma Chalmers faces is writ large from the 2023 story – reform is the key to rising living standards and higher productivity yet people are resistant to change, suspicious of lecturing politicians and reluctant to make sacrifices for the greater good. Australia seems trapped between a culture of complacency and the need for robust reform to revitalise our national arteries. It is no surprise the Treasurer says “the 2020s must be about the end of complacency”.

Albanese has led a government focused on the delivery of its specific promises – better childcare, action to boost wages, support for the care economy, the safeguards mechanism to reduce carbon emissions, more university places and fee-free TAFE places, intervention to underwrite the renewables sector, a National Reconstruction Fund to boost local manufacturing, more funds for Medicare and housing availability, and a budget bottom line likely to see two successive surpluses, mainly courtesy of the revenue surge from commodities.

Its performances suggests Labor is a government of steady and incremental change. It is not a transforming government though it aspires to be transforming government over time. But will it be granted that time by the public? Can Albanese Labor deliver the first long-run government since John Howard? That remains an open question at the end of 2023. Since 2007 Australia has seen seven changes of prime minister in 16 years and in that time no PM has been re-elected. Albanese hopes to break that dismal cycle.

In the process his political skills will be pushed to the limit. Labor is fighting a battle with the Greens on the left of politics with every sign the Greens are making electoral progress on Labor’s left flank.

At the same time Dutton has proved to be a far more formidable Opposition Leader than Labor expected (witness its same misjudgment of Tony Abbott as opposition leader) with Dutton making progress eroding Labor’s position in outer suburban seats.

On immigration, Labor has scrambled to reset the program but its slow response has come with a political prices. With arrivals scaling 510,000 last year Labor has re-designed the program but stood by a strong demand-driven intake with numbers predicted to stabilise at 250,000 from 2024-25.

In the world Albanese and Penny Wong have sought to revitalise Australian diplomacy. Ties with China are re-established and trade sanctions are being removed. Albanese displays a skill in foreign relations few knew he possessed. He boasts about his personal relations with Joe Biden, but perhaps he boasts too much.

Meanwhile, Wong tirelessly has worked the Pacific neighbourhood where Australia must become a savvy metropolitan power.

Diplomacy is an asset. But the 2020s is a time of hard power, national rivalry and relentless competition. Diplomacy cannot substitute for power, strategic and economic, and if Labor overlooks this reality, its foreign policy is unlikely to succeed.

Perhaps the ultimate message from 2023 is that only a full-scale whole-of-nation response can meet the challenges Australia faces. The country needs to change its ways. It is far too slow and looks out of touch. It needs to become more agile, smarter and competitive. Government must lead and that means the states, not just the commonwealth. But Australia needs a better performance from its elites, people who have the power and influence but aren’t doing the job.

The year 2023 saw ominous forces remaking the world order, a global struggle by central banks to beat back inflation, and cultural eruptions in the West undermining the liberal principle of equality – it was branded everything from a polycrisis to an age of megatrends.