The war in Ukraine has created another ‘axis of evil’

Soon thereafter, trainloads of North Korean artillery shells started rolling to Russian troops in Ukraine — by American calculations, as many as one million munitions, or roughly three times what European nations had been able to supply in a whole year.

Another increasingly important partner of Russia, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi, visited with Putin this month. Iranian ammunition and drones have played a major role in the Russian war effort. Now Raisi discussed the desired payback: sophisticated Russian aircraft and air defences that would make it much harder for the U.S. or Israel to strike Iran and its nuclear program.

President George W. Bush used the term “axis of evil” to describe North Korea, Iran and Iraq in 2002, in his first State of the Union speech after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The idea was ridiculed by many at the time. But now an axis uniting Moscow, Tehran and Pyongyang has become a geopolitical reality — and with a revisionist and reckless Russia at its centre, it poses a growing threat to the U.S. and its allied democracies.

“These countries are showing an excellent burden-sharing. And when it comes to Ukraine, there is an unholy alliance of these forces which have achieved a war economy, whereas we in the West are unable to achieve an increase in the production of ammunition,” said Roderich Kiesewetter, a German politician and a former senior officer of the German General Staff.

This new axis is coalescing as the U.S.-led Western alliance is showing systemic cracks. Indispensable American aid to Ukraine has been stalled because of Republican opposition in Congress, and EU efforts to confront Russia have been sabotaged by Hungary. Neither the U.S. nor Europe has been willing or able to boost military production to match Russia’s recent growth in manufacturing ammunition and weapons.

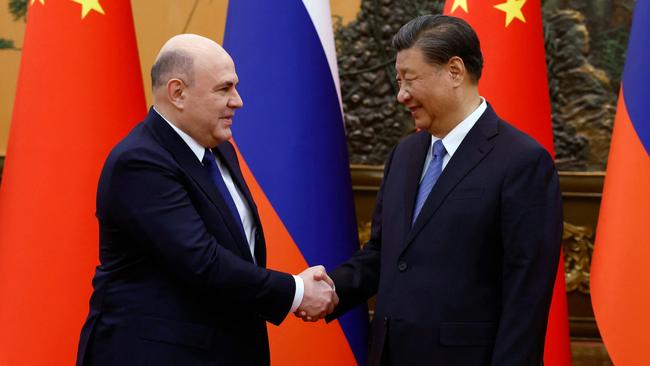

China, another authoritarian power, is friendly to the burgeoning Russia-Iran-North Korea axis but has not joined it militarily — though it may do so in the future, if Western resolve flags. “The Chinese are watching: how do we behave? And our responses are vague and not corresponding to our needs,” said Artis Pabriks, a former Latvian defence and foreign minister who now heads the Northern Europe Policy Center, a think-tank. “We have deeply underestimated the impact of Russian aggression in Ukraine.”

A new acronym has already emerged in Washington to denote this autocratic line-up: the CRINKs, meaning China, Russia, Iran and North Korea. These countries have increasingly aligned their positions not just on Ukraine, but on other crises that pit them against the U.S., such as the war in Gaza.

Such diplomatic co-ordination shouldn’t be underestimated, said Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, a New Hampshire Democrat and a senior member of the Foreign Relations Committee. “Russia gives Iran and North Korea acceptance and credibility, and it’s also one of the things that China provides to Russia: that they are not alone in the international community,” she said.

During George W. Bush’s presidency two decades ago, Russia was positioning itself as a responsible global power, and co-operated with the U.S. and other Western allies in moderating Iranian and North Korean behaviour. Even after Russia invaded Ukraine and annexed Crimea in 2014, it was one of the parties to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, a deal through which the Obama administration aimed to curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions. Until 2017, Russia voted for U.N. Security Council sanctions against North Korea.

But when the 2022 invasion of Ukraine failed to achieve regime change in Kyiv and prompted the West to funnel money and weapons to the Ukrainian government, Moscow’s calculations changed. With Russia crippled by Western sanctions, Putin has turned to other rogue states that could provide him with valuable military aid, and that crave Russia’s own technologies.

Iran’s Shahed drones entered combat in Ukraine in October last year, and have been extensively used against Ukrainian power stations, port infrastructure and military targets. Production of the drones is now partly localised inside Russia. Such field-testing in real combat conditions, against Western-supplied air defences, has allowed Iran to improve the design and the effectiveness of its drones, military officials say.

So far, Iran has stopped short of providing Russia with ballistic missiles, using that step as a bargaining chip in its talks with the West. Such restraint, however, could disappear now that attacks by Iranian-backed Hamas have sparked war in Gaza.

“The Iran-Russian military co-operation is really reaching new heights. It’s a stunning turn of events,” said Ali Vaez, director of the Iran Project at the International Crisis Group. Military ties between Moscow and Tehran were solidified by Russia entering the Syrian war in 2015, he said, and if Iran obtained Russian aircraft and air-defences, it could project military power across the Middle East. “Nobody else is willing to give them that kind of weapons,” Vaez said.

The Iranian missile program, and its military industries in general, have long benefited from North Korean know-how. But Russia has weapons that North Korea doesn’t produce. Iran’s weakest point is its lack of modern combat aircraft, and it has already signed agreements to obtain Russian Su-35 jets.

While the Soviet Union used to be a formal ally of North Korea, post-1991 Russia was wary, developing close ties with South Korea instead. That coldness turned into a nearly-obsequious courting of Kim when the Russian army confronted an ammunition shortage this summer. Accustomed to an overwhelming artillery advantage on the battlefield, Russian troops in southern Ukraine suddenly found themselves facing superior Ukrainian firepower on some sections of the front. Ironically, a large share of the artillery ammunition used by Ukraine during its summer offensive was provided, via American intermediaries, by South Korea.

In July, weeks after the Ukrainian offensive began, Russian defence minister Sergei Shoigu travelled to Pyongyang. At a military parade to mark the 70th anniversary of the North Korean “victory” over American forces, he stood next to Kim as troops marched by. When Kim made a weeklong visit to the Russian Far East two months later, he was showered with honours — a contrast to the relatively cool reception he had been given on his previous trip in 2019.

“We’re in a different world. Russia’s war has been unfolding in ways not entirely according to Putin’s plans,” said Sung-Yoon Lee, a specialist on North Korea at the Woodrow Wilson International Center. “Putin needs Kim, and Kim needs Putin. In this new environment, he added, the old Cold War dynamics in East Asia have returned, with Russia, North Korea and China on one side and the U.S., South Korea and Japan on the other.

This doesn’t entirely align with Beijing’s interests. China, unlike Russia, North Korea or Iran, has a trade-dependent global economy. For now, at least, it is seeking not to further damage relations with the U.S. or Europe — one reason why Chinese leader Xi Jinping has declined to provide weapons to Russia. Beijing is also wary of Russia encroaching upon its own privileged relationship with North Korea.

“It’s not in Xi’s interests that the Russians are pulling the Korean peninsula into the war in Ukraine,” said Victor Cha, Korea chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., and a former senior White House official. “It’s just causing a tightening of the U.S.-Japan-South Korea relationship, which makes China’s neighbourhood even more difficult.”

What exactly North Korea has gotten from Russia so far is unclear. Pyongyang successfully launched its first spy satellite at the end of November after previous failed attempts, an achievement that U.S. officials said could have been a result of Russian assistance. But so far there is no public evidence that Russia is sharing the ballistic-missile and submarine technology particularly sought by Kim.

“Russia wants artillery shells, but in return for that, you don’t have to help the North Koreans with cutting-edge military technology. There are other things that Russia can do: financial assistance, food aid, energy,” said James Brown, a professor of political science at Temple University in Japan. “It seems like Russia is deliberately playing up, for political reasons, the idea that they could provide advanced military technology. It’s a way to threaten South Korea and Japan that, if they continue to support sanctions and assist Ukraine, it will have consequences for them.”

The Wall St Journal

Beaming at every turn, North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un toured the jewels of Russia’s military industries in September. A guest of President Vladimir Putin, he gawked at the plant making Su-35 jet fighters, inspected a Russian Navy frigate and examined the Kinzhal missiles at the Vostochny spaceport.