Torn in the USA: Young Americans despondent about democracy ahead of 2024 presidential election

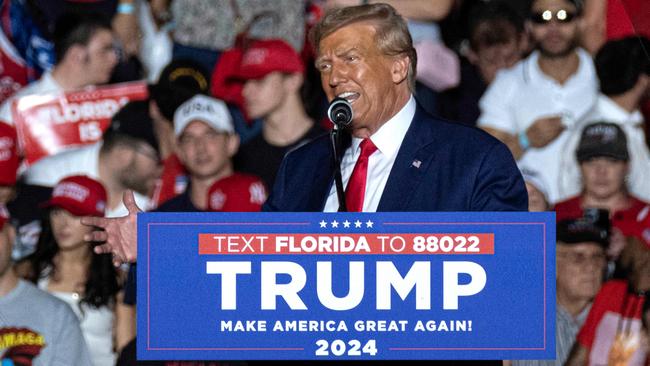

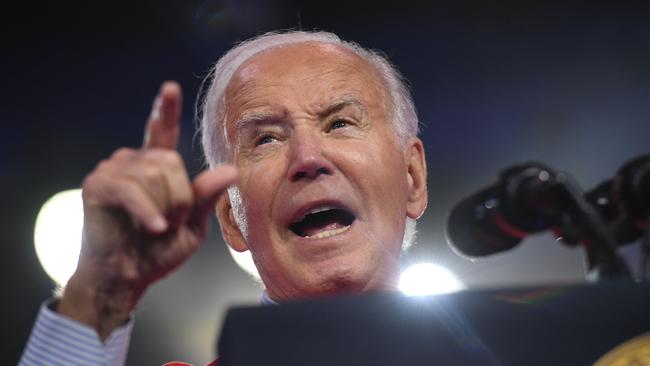

With a rematch between Joe Biden and Donald Trump likely in 2024 young Americans are despondent about democracy, but is this sentiment justified?

As soon as 2025 American democracy could begin to collapse, warned Canadian political scientist Thomas Homer-Dixon last year, reflecting the widespread view that democracy in America, and more broadly throughout the developed world, was under threat.

“We mustn’t dismiss these possibilities just because they seem ludicrous or too horrible to imagine… By 2030, if not sooner, the country could be governed by a right-wing dictatorship,” he wrote in the Canadian paper The Globe and Mail in January 2023.

Younger Americans, in particular, have become despondent about the future of US democracy: indeed 32 per cent of US college students said they preferred socialism, compared to 25 per cent who said they supported capitalism as a motivating principle for society, according to a North Dakota university survey in 2021.

In the same year 58 per cent of US adults told Pew Research they were not satisfied with how their democracy was faring, compared to a median of 41 per cent in 17 advanced nations (37 per cent in Australia).

As the 2024 presidential election approaches, and the likelihood of a rematch between Joe Biden and Donald Trump increases, doom and gloom about US prospects if Trump were re-elected will intensify.

“He would explicitly deploy the government against his political enemies, he would massively expand executive power and it’s likely that Congress would not stop him,” Claremont College university professor John Pitney told The Australian, reflecting a widespread view among mainstream elite opinion.

But the reality of US democracy and the socio-economic trends it has delivered don’t justify the sharp decline in confidence. The January 6th riots on Capitol Hill, prompted by Donald Trump’s insistence he didn’t lose the 2020 election, have cast a dark shadow over US democracy that isn’t warranted by the facts.

If the events of January 2021 were an attempted coup, as numerous Democrats and pundits suggest, then the lesson was one of US constitutional resilience not fragility. Even the vice president of the United States, Mike Pence, who as deputy head of state had a powerful personal incentive to seek to stay in power, didn’t consider Trump’s bizarre constitutional advice to reject states’ electoral votes.

The so-called insurrection, even one allegedly led by the most powerful man in the world, didn’t stand a chance against a constitution that was deliberately designed to thwart the emergence of dictatorships.

Even if Trump were the existential threat to US society as commonly believed, he is an aberration, and a 77-year-old one at that. None of the contenders for the 2024 GOP presidential nomination has offered a policy platform that points to a more powerful, intrusive federal government, indeed quite the opposite.

Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida and the second most popular GOP candidate for president at the time of writing, has promised to drastically reduce the power of federal health agencies and abolish the federal Departments of Education, Commerce, Energy and the Internal Revenue Service.

The US still offers a path to advancement, economic and social, in ways competing economic systems do not

The third most popular candidate, Vivek Ramaswamy, has promised to disband the FBI and CIA.

These policies must logically undermine the claim the GOP in 2024 seeks to empower the federal government; an autocracy is not possible without a powerful bureaucracy, especially without a strong police and surveillance apparatus and control of the national educational curriculum.

As for Trump himself, to the extent his term as president offered any insights as to his inclination to destroy US democracy after 2024, his term was characterised by little new legislation beyond a major tax cut, and a cabinet of ministers who often publicly disagreed with each other and him, which has never been a hallmark of totalitarian systems.

Indeed, some of the criticism of Republicans could equally be levelled at some Democrats and left of centre politicians in most advanced nations who were typically most in favour of draconian and unprecedented public health policies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Governments in effect suspended traditional human rights code in relation to speech, movement, commerce, and produced propaganda designed to scare citizens into compliance, at the same time as censoring disagreement in partnership with social media giants. This could be described as autocratic.

Since the 2020 election much of the panic about the future of US democracy has centred on alleged Republican efforts to make it harder for Democrats to vote, especially in the swing state of Georgia, whose Republican governor has curbed the availability of after-hours voting at “drop boxes” (a voting method never permitted in Australia).

Yet for all the criticism, voter turnout in 2022 in the state’s midterm elections was even higher in light of the reform, reflecting new academic research that suggests such reforms don’t matter anyway.

“There is little evidence in the scholarly record suggesting contemporary election rules affect political outcomes: most laws barely make a dent on voter turnout, let alone affect who wins or loses,” concluded political scientists Justin Grimmer and Eitan Hersh in research published in mid-2023.

In essence, they found legal changes that have the effect of depressing voter turnout for subgroups of the population, such as black or Latino voters, only have tiny impacts on the ultimate vote tallies for either of the major parties. Their impact on turnout simply isn’t great enough to change the overall results, they found.

More broadly, voter turnout has trended upwards in the US over the last century, reaching a near record high above 65 per cent in 2020, according to Election Project, suggesting Americans have become more, not less, engaged in the political process, whatever they might tell pollsters.

Only about half of 18- to 29-year-olds bothered to vote in the 2020 presidential election, although the share had increased from 39 per cent in 2016, according to the Center for Information and Research at Tufts University.

The US in many respects is the most democratic country in the world: judges, police chiefs, public prosecutors, school oversight boards are often elected, in contrast to practice in Australia and European nations, along with a national House of Representatives that’s voted upon every two years.

The thresholds for state referendums are surprisingly low too, giving ordinary people a mechanism to force their will on their own governments (interestingly, this is one of the ways decriminalisation or legalisation of marijuana has spread across US states, often contrary to the wishes of local politicians).

Yet in other ways, the US is not a democracy, but a constitutional republic, with provisions deliberately designed to thwart majoritarian rule, such as a constitutional Bill of Rights, an unelected Supreme Court with lifetime tenure, a senate with equal representation of states regardless of their population.

The US president is elected by an electoral college made up of designated state-chosen electors. Donald Trump became president in 2016 without winning the “popular vote”, just as George W Bush did in 2000, but this isn’t a new phenomenon: incoming presidents didn’t win it in 1824, 1876 and 1888 either.

Perhaps the main reason why Americans shouldn’t be despondent about their democracy is its extraordinary success in generating wealth for ordinary people. According to analysis by the Financial Times in August 2023, Mississippi, America’s poorest state, is richer per capita than the United Kingdom after adjusting for prices, excluding London. It’ a stark reminder of how poor much of Europe, where government regulation looms much larger, still is in comparison to the US.

Significant and growing inequality in the US tends to obscure the fact that real median wages have grown faster there than in most other nations. According to the OECD, US average wages, adjusting for purchasing power, were the third highest in the developed world in 2022, behind Iceland and Luxembourg.

Such aggregates obscure the social decay that’s blighting America’s biggest cities – rising crime, declining economic mobility, failing public education – but the autocratic alternatives remain far worse.

The US still offers a path to advancement, economic and social, in ways competing economic systems do not.

China and Russia, the world’s two emblematic autocracies, remain grindingly poor by comparison to the US, even despite decades of rapid economic growth in China, and riddled with corruption. The insatiable demand to migrate to the US, evidenced by the historic surge in immigration on the border with Mexico, is testament to the superiority of US economic outcomes. Russia’s and China’s populations are shrinking.

Younger Americans should be careful what they wish for.

Just as the pessimism within the US about the country’s future is centred on the alleged threat posed by Trump, a handful of politicians in other democracies – Marine Le Pen in France, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Narendra Modi in India, and former president of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro – have contributed to a perception of global “democratic backsliding”.

This phenomenon has been exaggerated too, a product of elite disdain for these politicians’ policies rather than any evidence they have sought to establish autocracies. Bolsonaro, who was defeated in the 2022 presidential election by former president Lula da Silva, didn’t seek to subvert the result, despite predictions he would.

Turkey’s president Recep Erdoğan only narrowly won re-election in 2023, for the first time having to contest a run-off election against his opponent who won almost 48 per cent of the vote, suggesting however distasteful the west finds his policies, he was elected fairly.

Sometimes evidence of “democratic backsliding” in less developed nations could equally be found in “gold standard” liberal democracies. In Israel, the conservative prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu has controversially sought to increase the government’s role in selection of judges, but this is common practice in Australia and many parliamentary democracies.

The democratically elected Orbán in Hungary has been accused of curtailing press freedom under the guise of “combating misinformation”. Yet governments in Australia, the US and the UK have proposed legislation to censor voices who disagree with them or worked hand-in-hand with social media giants to snuff out criticism, even when critics of government policy were expressing the truth.

If democratic “backsliding” has been occurring “over there”, it’s been occurring “over here” too.

President Biden has fed into this narrative of “democracy under threat” by casting the world increasingly as a contest between democracies and autocracies, a contest that’s supposedly come after Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine.

But the reality is more complex. Large democracies, such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico and South Africa, have not joined the US economic campaign against Russia. Furthermore, according to the Fraser Institute’s 2022 (most recent) annual ranking of economic freedom, Russia was freer than Ukraine, ranked 94th in the world compared to Ukraine’s 126th.

How have the perceptions of democratic backsliding and despair in the US and globally become so entrenched?

Despite the economic challenges the mainstream media has faced with the development of the internet, it remains immensely influential on public opinion, as citizens consume headlines almost 24 hours a day across their various digital devices.

When the overwhelming bulk of mainstream journalists sympathise with one side of politics – in the US they support the Democratic party – it’s only human nature that they seek to demonise or at least exaggerate the threat posed by the main political party, even if newsrooms try to make a conscious effort not to. A University of Texas survey of elite US journalists in 2018 found 0.5 per cent called themselves “very conservative” while overall only 4.4 per cent said they “leaned right”.

The result of this institutionalised bias in the media is the creation of a perception that one party or figure is an existential threat to democracy, when in reality it, he or she simply reflects different political priorities to those held by large minority or majority of the voting public.

From the Ancient Greeks to Alexis de Tocqueville in the 19th century, critical observers of society have worried about the longevity of democracy, given its innate tendency to produce populists who might seek to whittle away at constitutional protections or outstay their democratic welcome. So far they have been proved wrong.

It is highly unlikely the US careens into autocracy after 2024, even if Donald Trump were re-elected for a second term.

As Churchill once remarked, democracy is the worst of all political systems except for all the others, something enough people, even in a highly polarised political environment, appear to understand.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout