Two former PMs have raised the alarm. Will they be heeded?

Shared morality, once the glue that held the social fabric together, is being torn apart while the broad political spectrum in which social democrats, conservatives and card-carrying liberals live together is under deep strain.

Yet these warnings are irrevocably linked. They testify to truths that virtually nobody in public life will utter. They reveal something bizarre about our information-soaked society – the reluctance of elites to talk about what is really happening to Australia. Is the consequence of the technological age the dumbing down of our self-understanding?

Australia is now a fragmented nation – divided over fundamental belief, engaged in a democracy-changing experiment with the smartphone and losing trust in institutional authority. In this context the power of prime ministers to drive the enduring change Keating seeks is significantly diminished, with Newspoll this week showing the Labor primary vote at 33 per cent and the Coalition at 36 per cent. The once great governing parties are shallow relics of their history.

In his valedictory this week Morrison identified the pervasive source of our human unhappiness – warning that the ongoing assault on our civilisational traditions will undermine the good society, mutual respect and the moral order.

Morrison was speaking to everyone, religious and non-religious. He said: “We should be careful about diminishing the influence and the voice of Judeo-Christian faith in our Western society, as doing so risks our society drifting into a valueless void.” In that space “there is nothing to stand on, there is nothing to hold on to”.

You may decide Morrison doesn’t deserve your attention. Yet he was probing the issue of our times: the crisis facing Western democracy in the 21st century with the public aware that something has gone badly wrong but confused about the origin of the problem. In the process Morrison alluded to a related truth – the limits of politics. He said “all political philosophies and ideologies, including my own, are imperfect and regularly confounded by events outside our control”. In a society walking away from religion, those looking to the political realm for personal sustenance are engaged in grand folly.

Morrison said people didn’t need “to share my Christian faith” to realise that the erosion of the Judaeo-Christian tradition would ultimately undermine the norms and principles that govern the cohesive society and established order. If you dispute this, consider the scale of our disintegration.

In Australia today, the public is unsettled and getting more unsettled. People distrust the nation’s direction, some probably fear the “valueless void” while others are alarmed about the mental illness contagion among young people, the elevation of personal feelings as the basis for morality, the decline in core school standards, the rejection of objective truth, uncertainty over who is a man and who is a woman, the demand for group identity rights based on race, sex and gender, the erosion of free debate on university campuses, the disputes over whether our history is to be honoured or denounced, constantly lecturing elites who fail as genuine leaders, the lost ability to disagree with mutual respect and, above all, the doomed demand for leaders to display moral values amid a society that cannot agree on what constitutes virtue.

This is a fractured society. Not as fractured as the US. But the shared morality, once the glue to hold the social fabric together, is being torn apart. An alarming number of people are damaged, lonely or depressed. This is the road Australia is travelling.

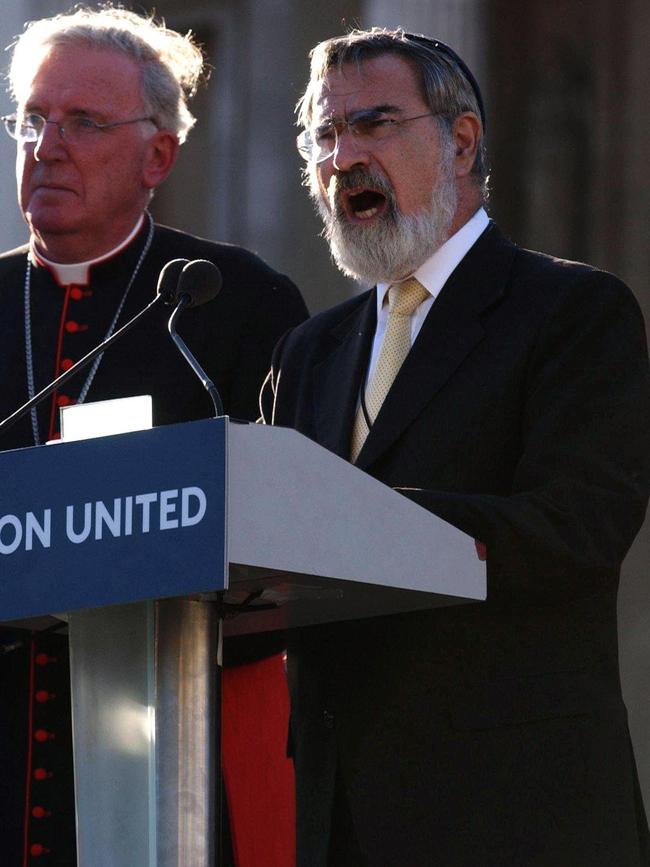

That great moral leader of our times, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, said: “A free society is a moral achievement, and it is made by us and our habits of thought, speech and deed. Morality cannot be outsourced because it depends on each of us. When there is no shared morality, there is no society.”

Knock out the civilisational traditions originating in Christianity that are the foundations of our moral order and you knock out the bonds keeping our societies together at the exact time powerful centrifugal forces are working to pull them apart – witness the digital revolution and the progressive cultural revolution.

In his recent interview with the Australian Financial Review, Keating said: “To come of age, Australia has to have a new and altogether different idea of itself. Our circumstance is a sad indictment of our lack of pride and wilful incapacity to do anything material to head down a new pathway.”

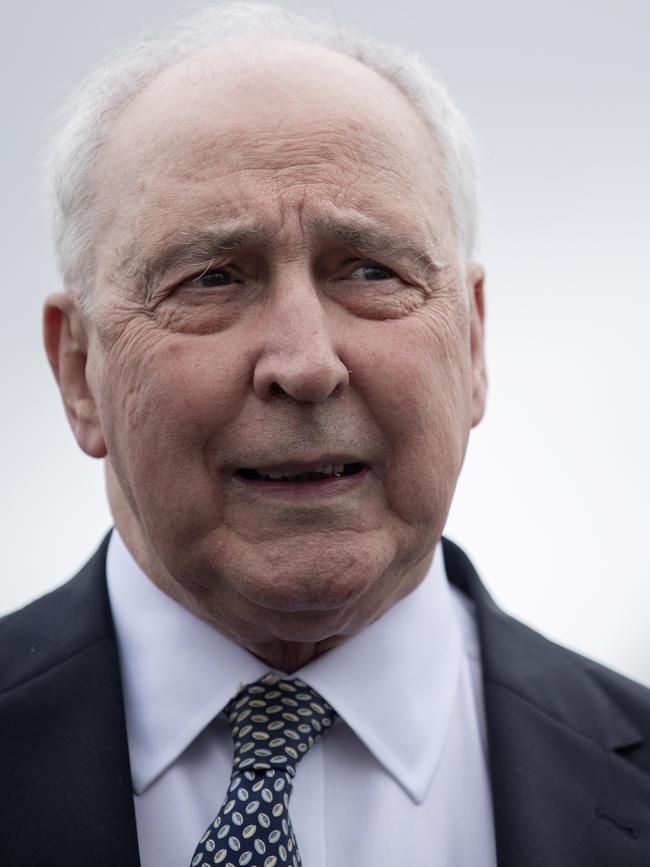

Referring to the dearth of reform and national imagination, Keating, who celebrated his 80th birthday in January, said Australia had much going for it: resources, sunshine every day and a huge pool of savings for investment.

“We should be killing it,” he said. “Instead of that we’re all the time timid, the whole thing is timid and there’s no what I call successful thinking. This timidity sort of seeps; it’s like a perspiration in the country.”

People can agree or disagree with Keating’s policy vision. But few can dispute his lament that Australia has lost its way on numerous fronts – economic growth is weak; per capita incomes languish yet economic reform is barely registered; social progressivism is an article of faith; the culture war is entrenched; Indigenous reconciliation is marooned; and governments are strong on short-term politics yet weak on deliverable vision.

There are many reasons but a fractured society is top of the list. It’s the old football adage: you can’t have high ambition with a fractured team. The failed voice referendum rang the bell – the country was split 61-39 per cent on a decisive moral question. When a country is fractured the obstacles to mobilising majority-endorsed change are immense.

Politicians won’t take the risk. There is too much grievance harnessed against them, too many negative campaigns, too many angry people aroused by social media activism. Above all, there are too many competing moralities. To paraphrase Sacks, when shared morality disappears then political progress is a forlorn hope. This is Australia’s fate. When a nation is fractured, trust is lost and politics sinks into a quagmire.

When the culture is broken the way Morrison warns against, then the national advance to which Keating aspires inevitably succumbs to reoccurring failure.

In 1984 a young Anthony Fisher, before entering the church and long before becoming Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, visited Florence where he met two young Americans. They asked him if there was anything to see in Florence! He took them to the Uffizi Gallery when one of them turned and asked him: “Who is the woman with the baby in so many of the pictures?” They didn’t know who Mary and Jesus were. But you begin to wonder: how long before half of Australia’s young people will ask the same question.

This isn’t just an undermining of religion. It’s a large-scale assault on our civilisational heritage from which most of our art, literature, architecture, our sense of beauty and our understanding of human nature were bequeathed to us.

After the defeat of the voice referendum, Australian National University election surveys co-author Ian McAllister said of Australia: “I think there is a real values gap here. I think populist sentiment in Australia is pretty similar to what you find in Britain and the US, if you look at the Brexit vote or people voting for Trump.”

Donald Trump is the ultimate political symbol of the broken culture of the West, though to be fair there are many rivals for that dismal title. Trump said recently that as president he told NATO allies he would encourage Russia to do “whatever the hell they want” to European countries not properly financing their militaries. Did Trump say this? Who knows? As president he was a chronic liar.

Yet his flirtation with Vladimir Putin is known. Trump thinks he has mastery in negotiating with autocrats. He has boasted that, if re-elected, he would end the Ukraine war within 24 hours. Obviously, Putin is awaiting the US election to see whether he will be given the gift of a Trump victory.

The bigger issue is the decay of US politics and the prospect that Trump, who refused to accept his 2020 election defeat by Joe Biden and therefore sought to sabotage US democracy, will be rewarded by American voters.

Sadly, among Trump’s backers are a deluded bunch of Christian conservatives, testimony to how the fracturing in US life has penetrated into its religious community. American writer Yuval Levin has captured the pros and cons of the revolution sweeping the West: “In our cultural, economic, political and social life, this has been a trajectory of increasing individualism, diversity, dynamism and liberalisation. And it has come at the cost of dwindling solidarity, cohesion, stability, authority and social order.”

The quest of political progressives is to re-engineer the culture. It is now defined by what the individual prefers it to be. Levin says that once your guiding star is self-expression, “we are naturally inclined to recoil from any demands that we conform to the requirements of some external moral standing – a set of rules that keeps ‘me’ from being ‘the real me’.”

This is the new virtue. It asserts the true moral position is “being true to my feelings”. Being authentic is the new, ultimate cultural prize. It is a sentiment invading universities, public service employment, corporations and community organisations with its deluded claim that the state, church, military or virtually any authority must change their ways and adjust their moral principles.

Pivotal to the West’s dilemma is the cultural poverty of elites. Of course, they would never accept being lectured by Morrison, given the flaws he displayed in office.

But Morrison’s point is precisely that made by American analyst Francis Fukuyama writing about the evolution of the political order: “The rule of law in Europe was rooted in Christianity.”

It was church law that initially broke down tribal norms by recognising the claims of the soul, a stance that finished with the idea of universal human respect.

One of the celebrated American founding fathers, the second president, John Adams, said: “Our constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

The American founders rejected any established religion but they believed their political experiment would rise or fall according to shared human virtue.

The first president, George Washington, said: “Religion and morality are the essential pillars of a civil society.”

The founding fathers had little enthusiasm for Christian theology but they valued the role of Christian tradition – this is the key point for Australia today. You don’t need to believe in the Holy Trinity to grasp the defining value of Christian tradition in shaping civilisational norms.

Does the reverse argument also apply? It was Dostoevsky, studying the French Revolution, who said: “Revolution must necessarily begin with atheism.” Unlike Dostoevsky, we have the benefit of observing the Russian and Chinese revolutions – and history suggests he was right. The Russian and Chinese method was to elevate Marx by first destroying God. The great Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn captured the history of modern Russia in one sentence: “Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this happened.”

Respect for civilisational tradition doesn’t mean there should be more religion in politics. Just the reverse, as Sacks said: “When religion becomes political or politics becomes religious, the result is disastrous to religion and politics alike.”

However, the culture war between progressives and traditionalists has long been waged in Australia in reoccurring cycles of fierce engagement. It is fundamental to the growing fracturing in our society because it is a conflict not just of ideas but of morals – it goes to what we believe and who we are and what we want to be called. This is not the usual cross-party struggle. It is conducted within politics but also inside nearly all institutions, great or small, public or private, with the education system being the cradle of progressivism.

The progressive manifesto is that Western liberalism is immoral with its tolerance of white supremacy, colonisation and invasion, racism, sexism and patriarchy, climate action cowardice, tolerance of inequality and acquiescence before a capitalism too exploitative of workers and too greedy for owners. American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt said the struggle in the US between progressives and conservatives was akin to a battle between “different cultures” – an explicit recognition that the “shared morality” Sacks championed no longer existed in the US, a view probably reflective of its politics since 2016.

Haidt warned: “We just don’t know what a democracy looks like when you drain all the trust out of the system.”

Australia has not slipped that far. But our broad political spectrum of liberalism in which social democrats, conservatives and card-carrying liberals operate, contest and live together is under deep strain. The extremes of both left and right have more traction.

Sadly, as the universal ethic of liberalism comes under assault, the West is reverting to a new form of tribalism – based on identities formed by varying loyalties to race, sex, gender or religion. The more this takes hold, the more remote is any hope of an escape from the fractured society.

Morrison and Keating have very little in common, apart from being ex-PMs. The interesting feature is that their comments – strongly reported at the outset – have provoked no lasting debate.

As a nation, debate about the big issues – the origins of our cultural, democratic and policy malaise – are just too big to handle.

Two former prime ministers have warned about the state of our political life. The warnings could not be more different – Scott Morrison says any abandonment of Judaeo-Christian faith will diminish our nation and Paul Keating laments that “the country is so timid” and has lost its high ambition.