Anthony Albanese must seize the moment to face future challenges

We must have an urgent conversation to address the coming challenges that government can no longer ignore.

Since it was founded by Rupert Murdoch in 1964, The Australian has provided unparalleled news and analysis to the nation. As the newspaper enters its 60th anniversary year, we have invited some of our senior journalists to give their views on the future in their areas of expertise. We begin a short summer series of articles with this thoughtful essay by the peerless master of political history, Paul Kelly.

Australia is heading into a future of multiple challenges defined by the need to improve its economic performance, lift living standards and manage the transformations from technological innovation, climate change and geo-strategic threat.

Australia is part of the immense 21st century experiment: can Western democracies keep thriving in a world they have never before experienced? The task for Australia is to improve on its domestic underperformance of the 15 years since the 2008-09 Global Financial Crisis while tapping into opportunities offered by shifts in global power and economy.

The country needs to be agile, smart and internationally competitive. Above all, it needs to act faster and escape from much of the heavy regulation and bureaucracy that burdens decision-making and implementation.

The immediate challenge falls upon the Albanese government and its senior ministers, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, Treasurer Jim Chalmers, Defence Minister Richard Marles and Foreign Minister Penny Wong. But it goes far beyond government – the coming era will test Australia’s elites and decision-makers in companies, trade unions, the public service, the universities, the professional classes and the media.

The future belongs to nations that have internal coherence and a sense of shared national purpose. This is the foundation for effective leadership. The potent threat is internal dislocation arising from weak economic results, excessive inequality, cultural division and a loss of shared values. In politics, the chief task is to restore the political centre and check the destructive polarisation based on the extremes of Left and Right.

Politics is a symptom of deeper cultural and economic forces. For almost a decade political dysfunction has been the dominant theme in much of the West, notably the United States and the United Kingdom. While Australia has been spared the worst – assisted by its compulsory voting – it is not immune from the systemic tribulations of the rich democracies. The political risk is a fractured system where the quality of public policy declines – a test for Australia’s future.

When launching the August 2023 Intergenerational Report sketching the trends shaping Australia over the 40 years to 2062-63, Treasurer Chalmers said: “At a time of change, one goal is clear, pressing and foundational. To make Australia the biggest beneficiary of the shifts under way in our economy in ways that create more opportunities for more people. This is how we own the future.”

Australia suffers the problems of other rich democracies – a hardening of the economic and social arteries when audacity and mobility are the qualities required for the future.

Chalmers identifies five generational revolutions that lie ahead: the transition from fossil fuels to renewables, the shift from information technology to artificial intelligence, managing the demographic time bomb from an ageing population, the rise of the care economy and the retreat from globalisation towards a world more divided and burdened by geo-strategic danger.

Any one of these challenges would be daunting. But they arrive in a fusion that is complex and devoid of any “silver bullet” answer. Yet they must all be addressed. Chalmers says each is both a challenge and an opportunity. He said: “Across the board these five big shifts in our economy and society compel us to make the most of the energy transformation, foster a digital revolution that works for, not against us, provide quality care for an ageing population, prepare our people for work in new and broadening industries and locate and leverage our economic interests in an uncertain world.”

In short, the tides of change cannot be resisted. Nations and their leaders will need to possess three qualities for future success: intelligence to formulate the necessary national strategy; resolve to implement the policy prescriptions required; and the indispensable art of persuasion – to bring the public to cross the bridges that lie ahead.

This won’t be easy. Australia suffers the problems of other rich democracies – a hardening of the economic and social arteries when audacity and mobility are the qualities required for the future.

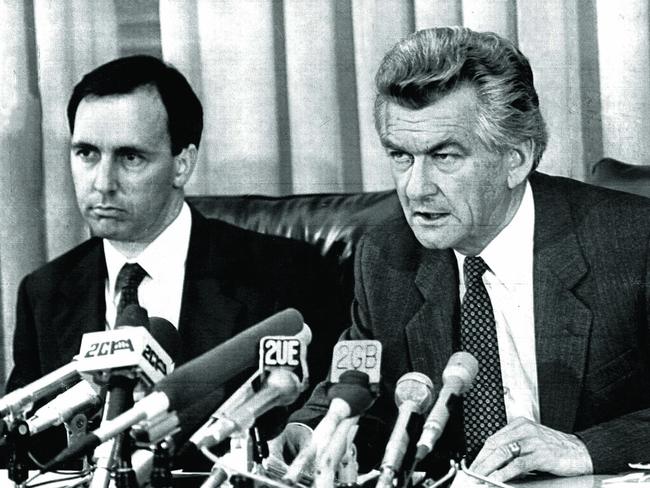

The national conversation along these lines is urgent. It needs to be launched now and run for years. What is required is nothing less than a change in Australia’s political culture. It is not beyond us. During the great reform era – running from 1983 under Bob Hawke and Paul Keating and maintained by John Howard and Peter Costello – till around Howard’s final term in 2004-07, Australia engaged in possibly the most comprehensive reshaping of its economic and social policies and institutions of any industrial democracy.

Australia became a state-of-the-art global leader. That spirit of ambition and resolution needs to be resurrected. It begins with a frank discussion with the Australian people. The narrative has been put on the table, notably in reports from the Productivity Commission, the latest IGR and the August report from the Business Council of Australia titled “Seize the Moment” the most comprehensive document from the corporate world on the nation’s future.

The Productivity Commission warned that over the decade to 2020 average annual labour productivity growth in Australia was the slowest in 60 years, failing to just 1.1 per cent compared with 1.8 per cent over the 60 years to 2019-22. The consequence of such difference is mammoth. For example, the time it takes for economic output per person to double increases by 25 years – approximately the length of a generation, from about 39 to 64 years.

The BCA blueprint warned Australia’s economic base was too narrow. Six products: coal, iron ore, natural gas, education, gold and wheat make up 60 per cent of Australia’s exports. On current trends the size of Australia’s economy by 2050 will fall from 13th to 21st on the global table, behind Mexico, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Turkey and Bangladesh among other countries.

Business investment is near a 30-year low as a proportion of GDP. The nation suffers from project announcements followed by project choke. It takes years and multiple approvals to launch new projects. Too few new businesses are being created. The public, after the Covid-19 experience, looks too much to state power to solve problems. Inventions are not being scaled up to penetrate global markets. This point is that more of the same is not adequate. There is a widespread recognition of this reality among decision-makers. The public is restless and impatient. It wants more action and higher living standards.

Where Australia has strengths they are conspicuous – the nation excels in resources, mining, agriculture, finance, education, creativity, migrant inclusion, areas of scientific research and community co-operation. They constitute a powerful platform for higher ambition.

The future will be a picture of many, different contradictory forces, operating across intersecting domains. It is likely to be a story of rapid changes in global power amid a multilateral world, wealth expansion, the struggle in democracies to retain the social impact, periodic crisis triggered by climate, environment and financial institutions, technological breakthroughs that enhance human life, the risk of pandemics, the prospect of large-scale people movement, rising cultural conflict between traditionalists and progressives, tribalism based on sex, gender and race, biological experimentation and the ever-increasing risk of catastrophic conflict from weapons of mass elimination.

Australia’s social values are more deeply entrenched than many realise, a vital asset in managing future shocks. Australia possesses internal strengths and resilience and has a proven record of managing change with skill and safety. Australia came to nationhood in a democratic vote of the population with the colonies agreeing to become states in the Federation.

Our constitutional federation based on public consent seems well positioned for the future. Australia has been a highly successful democracy for more than a century with an ability to grow and adapt. Its three main traditions are the British foundations, the migrant or multicultural contribution and the Indigenous inheritance, a story that will evolve in terms of respect, recognition and reconciliation. There is no reason to think our ability to combine these traditions in a cohesive nation will not be maintained.

However, the Intergenerational Report outlines the contours of Australia’s future growth and development and it reflects slower population growth and population ageing. Rich countries will demand more from governments, notably in health, aged care and asset accumulation. Current trends suggest real economic growth over the next 40 years at 2.2 per cent – that is 0.9 per cent below the average of the past 40 years.

Australia on current trends will have a population in the early 2060s of only a touch more than 40 million, far below the dreams of some founding father foreseeing a nation of more than 100 million. Migration will stay important but probably contribute a falling share to population growth. It means the domestic market will be relatively modest; Australia must succeed as a trading nation drawing upon its enterprise and international competitiveness. There is no other way.

But the decline in average annual income growth will be unmistakeable. On current trends the average real income growth per head will be 1 per cent over the coming 40 years compared to 2.1 per cent across the past 40 years. There are two main reasons – the decline in export prices for our commodities and the decline in our productivity. Australia will still be rich; but it will need to renew the creativity and aspiration of its great reform period to retain its rate of income growth.

This goes to ambition and motivation. There needs to be a pioneering or frontier spirit in approaching the future. That means striking a different centre point in the balance between security of life and boldness in innovation.

Much of Australia’s future depends upon its management of the two looming transitions – to net zero carbon emissions and the advance of digital technology. Combined they spell change on an unprecedented scale. The government estimates that decarbonisation needs an extra investment of $225bn by 2050 and it envisages that renewable energy will lead to the creation of new industries and export opportunities such that Australia becomes a renewable energy superpower.

Delivery on such vision is an immense challenge in terms of infrastructure, investment and public support given that high energy costs for consumers are likely to prevail for some years and reliability in the transition is imperative. The stakes for Australia are high. Its comparative advantage in fossil fuels will erode. Australia’s geology is rich in critical minerals needed for the clean energy world – there is confidence this will lead to new mining and value-added industries but that constitutes an arduous enterprise.

Current trends highlight the imperative for exceptional fiscal management in Australia for many decades. Deep forces will propel higher spending across health, aged care, the National Disability Insurance Scheme, defence and interest payments on debt. The size of government will increase significantly over the decades.

Taxation is expected to rise but, in this situation, tax reform is essential to improve the efficiency of the system overall and ease the contribution being made by personal income taxes. Tax reform is vital in keeping the nation competitive. One shock from the IGR trends is that without serious corrective policy, Australia’s budget will be in deficit for the next 40 years.

One lesson from the radical government interventionist stance of the Biden administration and its resort to tax breaks, government subsidies and trade protectionism is that while such policies might work for the biggest dog on the block, the US, they won’t work for Australia. There is a tougher, more competitive, more dangerous world coming.

The task for politicians will be to contain the risks and seize the opportunities, the point Chalmers makes. The challenge for Australia will be to maintain what it has done successfully in the past – grow the economy to buttress the good society.

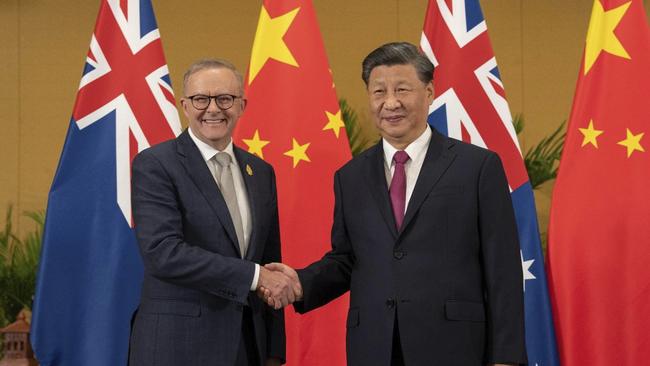

Global governance will remain a work in progress while nationalism will prevail, fuelled by the rising economic success and pride in developing countries. Competition between the US and China is likely to run for decades. Its course and outcome defy predictions but Australia will be deeply affected as a US alliance partner that has China as its major trading partner.

Recent decisions by the Morrison and Albanese governments have laid for basis for security strategies likely to endure for decades. Australia is investing more in defence. The defence budget is forecast to reach 2.3 per cent of GDP (still an inadequate level).

The AUKUS agreement means Australia will become a nuclear submarine nation, a whole-of-nation transformation. It will involve a more skilled workforce with Australia acquiring the technical capacity to build submarines at home in partnership with the UK and US. AUKUS Pillar Two envisages a wide range of technical co-operation between the three nations in terms of defence and security. The expansion of defence-related industry is slated as one of Australia’s most important advances over the next 40 years.

There will be a debate about civil nuclear power. That is inevitable. But any progress on that front will require the sort of political bipartisanship that delivered AUKUS – and that is hard to envisage at present.

Finally, Australia’s role as a metropolitan power will expand in relation to the South Pacific and Papua New Guinea. The immediate region will become a focus of rivalry as the competition between the US and China expands and intensifies. That raises the risk Australia will face potentially threatening military bases in the neighbourhood and far more intense strategic competition close to home. It will demand time, economic resources, diplomacy and new security arrangements.