These moments are shaped by the deeper instincts in our humanity and bring out the best in our parliament. Morrison and Anthony Albanese were warriors on Tuesday who put away their swords and offered tribute to their common cause – the Australian interest. In an emotional episode both spoke from the better angels of their nature. People familiar with the usual acrimonious rituals would have been astonished.

Albanese hailed Morrison “as a truly formidable opponent”, pointed out he governed during an extraordinarily difficult pandemic, saluted the quality and generosity of his valedictory speech, honoured Morrison’s family and, as a fellow member of the prime ministers club, said once achieved, that standing could never be taken away.

The paradox of Morrison was on display. As a politician he was assertive, driving and self-absorbed, his eyes fixated on the ultimate prize, yet as a Christian humbled by the imperfectability of human nature. He ruminated on Tuesday on the limits of politics and the false hopes vested in governments and markets, all being run by imperfect people “just like all of us”.

Morrison departs surrounded by contemporary dispute. He is loathed, even hated by many of his opponents, and the Labor benches on Tuesday were notably only half-full for the speeches. From his own side he is respected but largely unloved, seen as a prime minister whose ability was undermined by personal defects – witness the multiple ministries blunder that constituted misplaced prime ministerial egoism.

At the end Morrison opened his heart wider than before. Speaking as a politician and a believer, he said: “I leave this place not as one of those timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat. I leave having given my all out there in that arena and have many scars to show for it. I do leave behind in that arena any bitterness, disappointments or offences that occurred along the way.”

Morrison said his release from any bitterness is “due to my faith in Jesus Christ, which gives me the faith to both forgive but also to be honest with myself and my shortcomings”. His farewell speech had a powerful moral and cultural message for the nation – a message our politicians are frightened to speak and Morrison spoke only in his farewell. It is that Australia needs to retain the core of its being, its Judaeo-Christian ethic.

This is a religious position but transcends religion, going to the essence of our civilisation. He said “diminishing the influence and voice of Judaeo-Christian faith in our Western society” risks our “drifting into a valueless void”.

Why didn’t Morrison stand for this position and issue this warning as prime minister? Why, only now, does he talk in this way about his deepest beliefs? And if he had, wouldn’t he have been more successful? A skilled transactional politician, Morrison had two obstacles as prime minister – the Labor Party and a cultural revolution that he only poorly grasped and that he kept provoking.

Morrison’s faith, his social conservatism and his traditional view of families revealed a prime minister governing in an Australia undergoing a cultural transition defined by the rise of secularism, the elevation of human feelings as the basis for morality, and demands led by professional women for new rules, better behaviour and an end to discrimination.

Morrison’s flaw was lack of empathy when empathy became the electric current of political communication. He was a professional who missed that the mood and values of the nation had changed. But it wasn’t just women who turned against Morrison – it was the professional class.

The combination of Morrison’s personal failures – from the bushfire crisis onwards – and the cultural shift in professional class values brought him undone. To a significant extent Morrison lost the 2022 election on character grounds. In an astute campaign Albanese denied Morrison a major policy difference to exploit and then made Morrison’s character the central question. He was helped by the obvious reality – the government post-pandemic was weary, exhausted, and out of ideas for the future.

Morrison belonged to the post-Howard era of the Liberal Party when internal divisions over leadership, belief and tactics convulsed the party. Yet he had a lucky and successful career. Serving only 16 years in parliament, he spent nine years in office and had dominant portfolios – essentially immigration, social services, Treasury and prime minister.

He was in cabinet for the full nine years of the Coalition. His achievement in stopping the boats was conspicuous. From this time onwards he was a potential prime minister. As Malcolm Turnbull’s treasurer he supervised much of the journey towards a balanced budget while maintaining government services. Morrison was an endlessly calculating minister, competent, hardworking and with an unquenchable ambition to become prime minister that put off many colleagues.

In August 2018 Morrison outmanoeuvred Turnbull and Peter Dutton to come through the middle and take the highest office.

He won the 2019 election against the trend. Many of his critics misjudge that result. The extent of the polling recovery was virtually unprecedented and it is highly improbable that any other Liberal could have led the government to that re-election.

It gave the Liberals another chance. With the end of the Abbott-Turnbull chronic rivalry, the Coalition’s third term saw no internal challenge. Morrison and his deputy Josh Frydenberg had a close partnership, and Frydenberg remained loyal to Morrison and to party unity. Morrison became the 12th longest serving prime minister, between Paul Keating at No. 11 and John Curtin at No. 13.

He had an extraordinary prime ministership, dominated by three external events – China’s strategic assertion and its coercion of Australia, an event of international import; the pandemic that delivered not just a health crisis but the worst trauma for the federation in a century; and the global and domestic recession that threatened the highest jobless rates since the Depression.

On each front, Morrison’s achievements were significant. In retaliation, he internationalised China’s coercion, deepened ties with Japan and India, backed the Quad and was the originator of the AUKUS agreement for the development of nuclear-powered submarines in his negotiations with Boris Johnson and Joe Biden. That initiative is bipartisan. The Albanese government has assumed its political ownership. If it comes to fruition, over the decades Morrison will be seen as architect of one of the most important defence and foreign policy initiatives since World War II.

Australia’s economic response to the pandemic measures as implemented by Morrison and Frydenberg saw the most intense era of economic decision-making since World War II, co-ordinated with Treasury and the Reserve Bank. Yes, they spent too much. But they minimised the economic damage, saw unemployment return to historically low levels and delivered world-leading outcomes among OECD nations.

The pandemic response was blighted by the slow vaccine rollout and ongoing political battles between the premiers and Morrison. Mistakes were made in Australia – but far less than in many other nations. Australia had one of the lowest fatality rates from Covid in the developed world, with Morrison saying more than 30,000 lives were saved.

When history assesses Morrison’s performance as prime minister, much will flow from his handling of the three principal challenges on his watch, each being a world-defining event. So far contemporary assessments seem anxious to avoid this precise task, preferring an emotional focus on the rich list of Morrison’s flaws. And there are plenty of them. It is a safe bet, however, that as the tyranny of the present fades, history will reveal what really mattered and Morrison’s record is likely to loom in far more favourable terms.

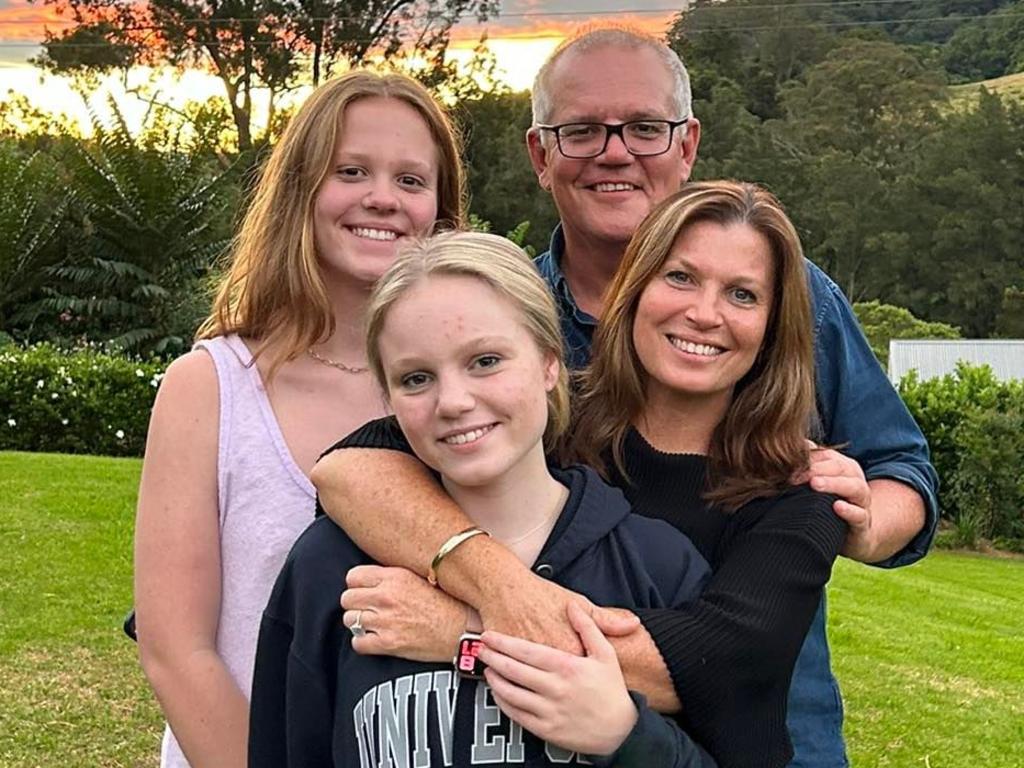

Scott Morrison had no finer moment in politics than taking his departure on Tuesday. On display were the qualities that took him to the prime ministership – a personal life anchored in family and faith, a spirit of combat that left “nothing on the field”, an attachment to community in the Shire and his ambitions in economics and national security.