Spectre of jihad rises up to threaten the world once more

An astonishing revelation from Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil reveals the shape of the terrorist threat to come. Part of it, oddly enough, arises from Covid.

Add to that the astonishing revelation from Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil that more than half of ASIO’s top priority investigative targets last year were minors, and you get a sense of how terrorism and terrorist indoctrination are changing shape. Protean and hydra-headed, it is not remotely vanquished.

Western strategic policy has moved on from the war on terror. Combating terrorism is no longer the organising principle behind US or allied strategic policy. The ground-force combat interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan – the conventional, industrial-scale manifestations of the war on terror – are over and almost certainly will not be repeated.

This is a sound, necessary move by the US and the West, including Australia, which committed troops to Afghanistan and Iraq. The overwhelming strategic challenge for Australians and Americans today is China. This will be so for the rest of the lives of anyone old enough to read this piece today. And the state power of the world’s other aggressive autocracies, most importantly Russia but also Iran and a few others, should also play a major role in shaping Western military capabilities.

As official Australian defence policy documents have recognised, we are returning to a phase of history in which state-on-state conflict is again the dominant security issue.

Western military forces – America’s and Australia’s – should never again be configured to wage a war on terror, for real wars of existential peril now loom as serious possibilities.

But that doesn’t mean the deadly scourge of terrorism has gone away. Within Western societies, the rise of right-wing extremism shading into terrorism has been a big story. But lone-actor or small-group Islamist jihadist terrorism also remains a potent threat. O’Neil outlined a shocking case of teenagers radicalising younger kids in the playground with Islamic State propaganda, including beheading videos.

Part of it, oddly enough, arises out of the Covid experience, with millions of Western teenage boys and young men spending months if not years alone in their bedrooms, with their screens and the poisonous sewers of the internet as their only friends.

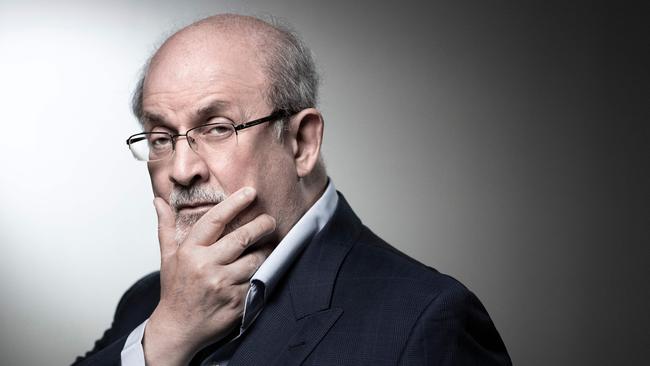

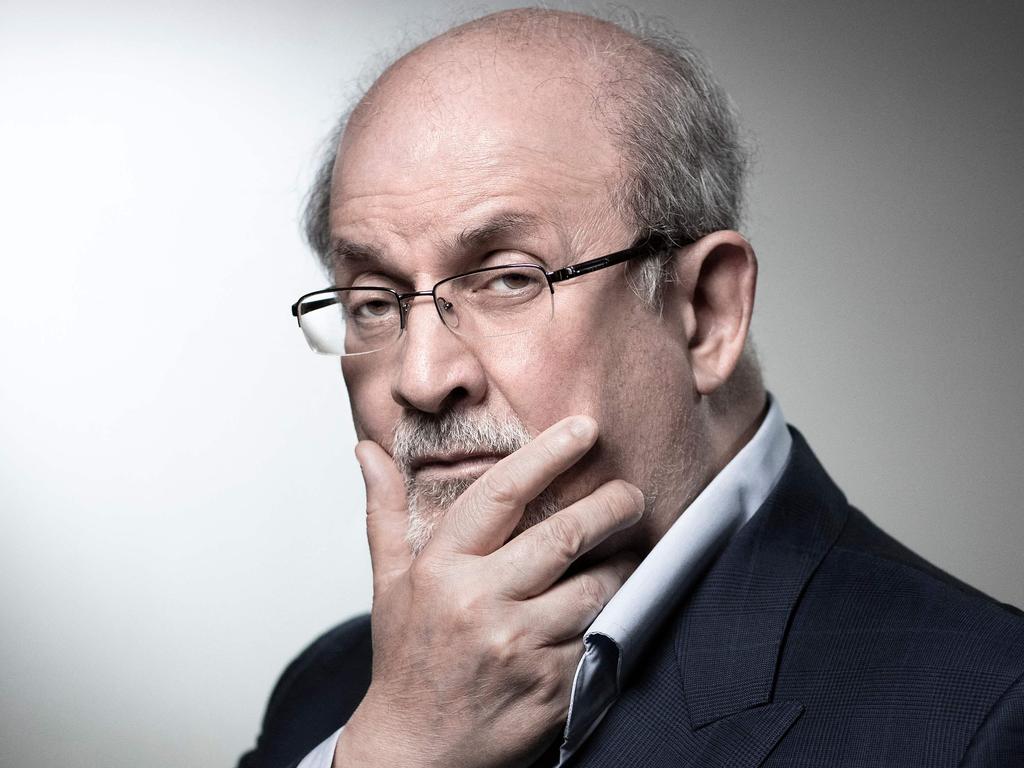

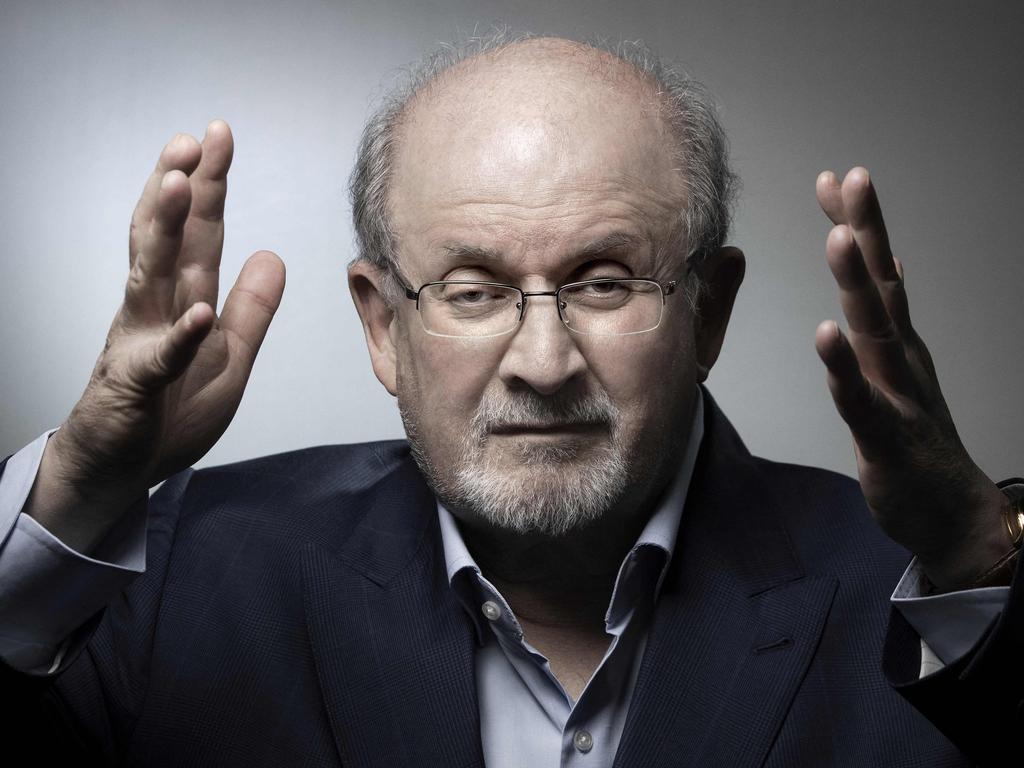

Western police forces and intelligence agencies have put a lid on Islamist terror at the macro level in Western societies, though terrible individual attacks continue, as evident in the hideous knife assault on author Rushdie at a literary centre in upstate New York.

Within Western societies the counter-terrorism response will have to be led by police and intelligence agencies and even community engagement. But in the broader world, terrorist and pro-terrorist movements are growing, gaining numbers, recruits, territory, plotting very big enterprises in the future.

Professor Greg Barton, an Islamist terror expert at Deakin University, tells Inquirer the global jihadist movements are overall stronger, with more followers, more believers, than they were before the 9/11 attacks of 2001. This is a sobering judgment from Barton, but not remotely outlandish. It is the consensus view among those who study terrorism.

Consider the contemporary centres of terrorism one by one. Afghanistan has been ruled by the Taliban now for a year. The Taliban has reversed its promise that women and girls would be able to pursue an education. As it is, girls cannot progress beyond primary school. The level of violence is a bit less than it was at the height of war. But no one could describe Afghanistan as a society at peace.

The Taliban can force women to cover up from head to toe, but it manifestly cannot run the society or the economy. The overwhelming majority of Afghans today are hungry. The Taliban itself faces a deadly insurgency from Islamic State Khorasan Province. Afghanistan has got back into narcotics.

Plainly, Afghanistan is also becoming a permissive location once more for terrorists. Barton tells Inquirer that hundreds of foreign jihadists are known to be moving back to Afghanistan.

The Americans were able to use a specialised drone to kill the fairly ineffective head of al-Qa’ida, Ayman al-Zawahiri. This is a remarkable episode in itself from many angles. Zawahiri was lounging on the balcony of a swank residence in one of the most up-market residential areas of Kabul. There are reports that the house was owned by a senior member of the Haqqani Network, which is part of the Taliban and part of al-Qa’ida. Sirajuddin Haqqani, the leader of this network, is regarded as the No.2 man in the Taliban government and in charge of domestic security.

Whoever owned the house, plainly al-Qa’ida now operates easily in Afghanistan. The US drone strike can be seen as evidence remote control counter-terrorism can work, although it may be that there was actually some human intelligence about Zawahiri’s whereabouts. But Afghanistan is a vast and mountainous nation, the US is unlikely to find many high-profile targets lounging on up-market Kabul balconies in the future.

In any event, the US has killed many leaders of al-Qa’ida and Islamic State without notably denting the capabilities of either organisation.

The Taliban itself is also reported to conduct its own targeted killings of Shi’ites, Hindus, Sikhs and anyone associated with the pre-Taliban government. The Taliban has its own internal tensions and could easily splinter into warring parties or more likely decentralise into localised war lord systems bound together only by jihadist extremism and a hatred of the West.

The terror groups that have always operated across the border in Pakistan are as strong as ever and cross-fertilise with many Afghan groups. In time these could cause growing problems for the Pakistan state.

As Afghanistan becomes more stressed economically, it is likely to become more lawless and less and less effectively governed. David Petraeus, who commanded US troops in Afghanistan and later became director of the CIA, wrote in an assessment of Afghanistan recently: “Islamist extremists will seek to exploit ungoverned, or inadequately governed, spaces.” He foresees the possibility of terrorist groups re-establishing sanctuaries and training facilities, the possibility also of widespread starvation, and the possibility of a huge surge of refugees from Afghanistan.

In the agreement that the Taliban reached with Donald Trump’s administration in 2020, it promised not to harbour terrorist groups and allow them to use Afghan territory as a base for operations against the US, in exchange for the US withdrawing from Afghanistan. Just like it promised girls an education. Petraeus writes of the Trump-Taliban agreement: “The ultimate peace deal we reached with the Taliban in 2020 that committed the US to withdrawal the following year, which we negotiated without the elected Afghan government at the table, has to rank among the worst diplomatic agreements to which the US has ever been a party.”

But Afghanistan is by no means the biggest or most dangerous state sponsor of Islamist terrorism. That dubious distinction belongs to Iran. The rulers in Tehran have, since the Iranian revolution in 1979, pursued a singular and consistent set of strategic objectives. They want to destroy Israel, harm the US and expel it from the Middle East, unite the entire Islamist world under their leadership (despite the Shia-Sunni divide) and ultimately acquire nuclear weapons.

The US and its allies in the Middle East have thwarted the Iranians, who have not achieved these objectives. However, as Karim Sadjadpour of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace argued in an important piece in Foreign Affairs earlier this year, Iran has made solid progress towards its strategic objectives, albeit at great economic and social cost.

Sadjadpour writes that Iran has established dominance in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen, the four failed or failing nations it describes as “the axis of resistance”. It controls a string of terrorist militias, most notably Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen. He says Iran now controls militias that number between 50,000 and 200,000 in total fighters. Most of these militias, and most of their efforts, are directed at local wars and local insurgencies and fights.

But Iran also wants to harm Western and especially US and Israeli interests. It sponsors Hamas and Islamic Jihad. These are Sunni groups and Iran is a Shi’ite power. But its early leaders were much influenced by the Muslim Brotherhood and did a great deal to promote the Brotherhood’s ideas. Iran is pragmatic about co-operating with the enemies of its enemies. It also believes that despite the Sunni-Shia split, which is often deadly and the fulcrum of much conflict in the Persian Gulf and throughout the Muslim world, all Islamists should find their inspiration from the Iranian regime, the only truly Islamist regime of any standing in the Middle East.

Like the Taliban in Afghanistan, the mullahs in Iran are not constrained by pious hostility to illegal drugs. Hezbollah is now a major trader in illegal amphetamines. There is a big drugs trade centred in Yemen as well.

Recently, Tehran’s agents have been discovered attempting to assassinate Iranian dissidents living in the US. The Biden administration has provided Secret Service protection for former senior officials Mike Pompeo and John Bolton, who are also threatened by Iran.

Although there is no direct evidence that Iran ordered the specific attack on Rushdie, it never rescinded the 1989 fatwa condemning Rushdie for his novel The Satanic Verses. On the face of it, it does seem a remarkable coincidence that all these other Iranian-sponsored attempted assassinations should coincide with the attack on Rushdie.

The Biden administration seems weirdly determined, no matter what Iran does, to negotiate an exceptionally weak nuclear safeguards agreement with Tehran. Trump tore up the last such agreement. It too was weak and lifted sanctions on Iran while allowing the Persian power to legitimise its nuclear industry and enrich uranium, all in exchange for a promise not to pursue nuclear weapons.

However, many serious analysts believe Tehran is determined to acquire nuclear weapons eventually and is inching ever closer to them. Sadjadpour describes Iran as obeying a “hierarchy of enmity” in which hatred of the US and Israel is more important than anything else. This is central to the regime’s entire existential purpose, which is why it cannot be moderated through engagement or definitively derailed through sanctions. It’s a very tough policy problem.

As if that’s not bad enough, there are vast territories beyond Afghanistan and Iran and its proxies where Islamist terror movements are active, influential, deadly and growing. This is especially so in Africa, in countries such as Nigeria, Chad, Niger, Mali, Algeria, Libya, Congo, Mozambique, Kenya and parts of Egypt. The groups in these countries are mostly local in their origins and actions but often affiliated with al-Qa’ida or Islamic State. Some are essentially large-scale criminal gangs. But it would be a tremendous mistake to underplay the Islamist ideological content of their beliefs.

The Western media does not pay much attention. Africa is full of problems. Frequently, these Islamist groups target Christian churches and communities, and the twisted anti-Christian reflex of so much of the Western media means this kind of atrocity is often played down, just as some Western media outlets seem to think terrorism against Israeli targets is not really terrorism.

It is also the case that while these terror outfits are often each others’ worst enemies, there is also a great deal of practical co-operation and dialogue among them. The pattern now is that even those affiliated with al-Qa’ida or Islamic State are not really directed by these central organisations. It’s more that they take inspiration from them or have adopted them almost as a franchise.

And then throughout moderate Muslim nations such as Indonesia there remains a substantial core of support for jihadist ideas. It may be a small proportion of Indonesia’s society that embraces such extremism, but a small proportion of a nation of 270 million can cause a great deal of misery.

The US, Australia and other Western nations must not lose focus on the predominant threat of our time, which is state-on-state conflict. But the global terrorist movement is growing. It is as nearly inevitable as anything can be that it will again find the means to hit targets in the West.

The best defence is development and stable government in the ungoverned spaces, but the terrorists themselves work hard to make this impossible. In these disturbed times, the terrorists will find their opportunities again.

You may have lost interest in terrorism, but terrorism has not lost interest in you. The first anniversary of Taliban rule in Afghanistan, the savage attack on Salman Rushdie, the relentless rise of murderous African jihadism, the depredations of Iran including its program of attempted assassinations in the US: these all tell us something about the shape of the terrorist threat to come.