Renewables ‘biggest change since white man turned up with sheep’

The land will be vastly altered: solar panels on the flats, wind turbines on the ridges and new high-voltage towers connecting it all, but the residents of these towns have more pragmatic things on their minds than rural scenery.

When Armidale mayor Sam Coupland looks at the maps and planning documents, the promised billions in investment and the sheer scale of what is roaring towards regional NSW, he neatly sums it up: “This will be the biggest change to the region since settlement in the 1840s.”

His shire is in the heart of Australia’s largest renewable energy zone, the New England REZ, 15,000sq km of land contained in a kidney-shaped squiggle on a map that includes Glen Innes in the north to Walcha in the south, with the university city of Armidale at its centre.

It’s a region of great beauty and character with rich agricultural land and historic hamlets, all hemmed to the east by the Great Dividing Range with its gorges, waterfalls and ancient forests.

The area has many attractions, but it’s the sunshine, wind and network of existing power lines that are luring developers who will transform this New England renewables patch into the modern-day equivalent of a giant power station.

A single outline on a map can’t convey what it will mean to host 8 gigawatts of wind, solar, pumped hydro and storage projects, so Coupland has found a straightforward way to explain its significance. “It’s going to be the biggest change since white man turned up with sheep in the 1840s. That fundamentally changed our landscape and this will too – and it’s happening whether people like it or not,” he says.

Pockets of land will be vastly altered: solar panels on the flats, wind turbines on the ridges and new high-voltage towers connecting it all, but Coupland has more pragmatic things on his mind than rural scenery.

Towns will overflow with hi-vis workers during the construction phase; roads will heave with over-mass and B-double trucks. Accommodation needs building; water, sewerage and roads upgraded; skilled workers found. Coupland says Armidale will be the dormitory for the REZ workforce and housing is already under pressure; water supply, too. It will be a boom time for some, but where there are winners there are losers too.

“All of the angst at the moment is centred around where projects are planned,” he says.

“So we have landholders who are giddy with excitement because of the financial windfall that is coming their way from hosting projects, then we have near neighbours who see all of the downside and none of the upside. To date, that’s all anyone’s interested in talking about, but it will be the town that feels the big impact.”

This is not just the future for New England. Itr is one of five dedicated renewables zones created by the NSW government: the most advanced is the 6GW Central-West Orana, about 20,000sq km around Dubbo and Mudgee; further west of Wagga Wagga is the South West REZ; along the coast the Hunter-Central Coast and Illawarra zones.

Coupland’s job as Armidale’s leader, and as chairman of a coalition of NSW rural and regional mayors, is to help guide the tsunami of renewables required to replace coal-fired generation, to ensure the promised riches deliver long-term benefits to communities. Services and infrastructure are one part of the equation; social friction in these tight-knit towns is another.

There are small community uprisings, groups protesting against the “industrialisation” of good farmland and the destruction of habitat and visual amenity, while others welcome the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Sheep farmer Dimity Taylor knows something of what’s ahead for New England. She lives in the rich farming area of Bannister, near Goulburn, southwest of Sydney. Around her home wind turbines line the ridge, a solar farm sits in the flat and high-voltage transmission towers from the HumeLink project will soon march near her property. She’s not worried by any of it. “We were concerned about the wind farms and they ended up being fine,” she says, looking out her kitchen window to seven wind towers on the horizon.

“We were worried about solar farms and they were fine too. There are already plenty of transmission lines in the landscape. I know this one (HumeLink) will be bigger but it’s probably not going to be as bad as what some people think.”

To meet Labor’s 2030 emissions reduction targets, Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen has forecast that 40 wind turbines need installing every month for the next six years and 22,000 solar panels every day. “Our local and regional communities are at the forefront of the economic shift,’’ he said.

Capital city dwellers are accustomed to a changing landscape. Homes and businesses are resumed for new roads and tunnels, high-rise apartments crowd out family homes; farming land on urban fringes is subdivided and transformed into a sea of black roofs, seemingly overnight. That’s the price of living in a major city.

In many rural and regional areas, change traditionally has been slower. Now it’s roaring towards them.

Michelle Park enjoys the outlook from her home in Bendemeer, a hamlet of fewer than 500 people on the Macdonald River between Tamworth and Armidale, on the southwestern boundary of the New England REZ. She loves the quiet, the big night sky and the small-town vibes.

“I always say to people, we don’t have doctors, we don’t have hospitals, we don’t have fancy restaurants, we don’t have all the things that you do in the big towns,” she says. “But what we do have are beautiful surroundings.”

People here enjoy their sense of place and some looked at plans for the Bendemeer Renewable Energy Hub close to the town with alarm. Up to 430,000 solar panels covering 350ha are planned within 1.8km (Park thinks it’s closer to 1.2km) east of the township, with 58 wind turbines to be built beyond that. “We’ve not been able to find one solar plant of this scale located as close to a village as this one,’’ says Park, who’s part of community action group Save Our Scenery.

Plans for a smaller solar farm on the outskirts of tourist town Mudgee, in the Central-West Orana REZ, were scuttled in the Land and Environment Court of NSW earlier this year because of its impact on visual amenity. Mudgee and a clutch of other regional centres including Armidale, Bathurst, Dubbo, Orange, Tamworth, Wagga Wagga and Goulburn, have been protected by state planning rules that stop solar and wind developments encroaching within 10km of a commercial centre.

Smaller towns such as Bendemeer have no such protection.

“We’ve been done over so badly by those who were supposed to represent us. Not only did they declare it a renewable energy zone, they put in no provisions whatsoever to protect towns and villages like ours,” Park says.

Mayor Coupland agrees the 10km rule should be extended to smaller towns. “There is no benefit to the towns from having a development close to them because the power is going right into the national grid. If it’s only going to cause downsides, it should go elsewhere,” he says.

To add insult to the residents of Bendemeer, the boffins carrying out preparatory work have used a formal rating tool to designate the town’s scenic quality as low to moderate.

“That’s not correct,” Park says. “Bendemeer’s value is in its landscape – that’s something you can’t really put a price on but others are looking at us and thinking: ‘Well there is no value there so who cares.’ ”

There’s a lot happening in this southern part of the REZ. A short drive north of Bendemeer, near Kentucky, the 32-turbine Thunderbolt Wind Farm has just been approved, and a bit beyond that the residents of Uralla are keeping track of developments mooted for their area.

“Within a 50km radius of Uralla there are, in some form of planning, some 900 wind towers and thousands of hectares of solar accompanied by the new transmission lines, hubs and batteries. This creates huge cumulative impact on a very small area,’’ says New England farmer John Peatfield, who is part of the community group Responsible Energy Development for New England.

We cover the nation

Coast to coast: Australia’s 200km metropolis

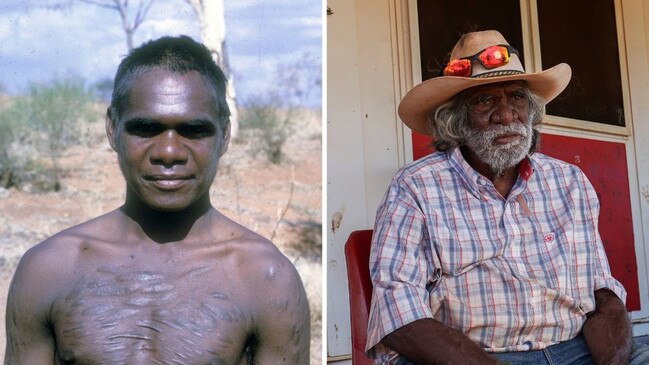

Out of towns and back to country: Visionary leads his people

Farmers put their livelihoods on the Line

Renewables ‘biggest change since white man turned up with sheep’

Should you give up your salmon to save a species?

Life in Australia’s most multicultural suburb

The energy boom presents a lucrative deal for landholders hosting the wind and solar, and developers pledge towns will benefit from generous community benefit funds. Neighbour agreements can help ease the friction, but in Bendemeer some landowners say aren’t interested in compensation that comes with strings attached.

Landholder and local real estate agent Kristy Reid, whose house will be located 2.1km from the nearest wind turbine, says the neighbour agreement will remove her right to protest. “Even during the construction phase, with the noise, the traffic and everything, you can’t protest,” she says. “They’re trying to shut us up.”

Her cattle and horse farm, in the family for 150 years, is in a picturesque valley looking out over the mountains. “Our view will be ruined because these turbines are going along the ridge that we look straight at. There’ll be flickering and at night, lights on top.”

Elise Robinson, who lives some 400m from the proposed solar farm, also values her rural outlook and tries to picture what the solar panels on a rise running the length of her property will look like. “It will be a completely black wall for us,” she says. “We love Bendemeer, we love the community, we love raising our children here. We just don’t want to see it destroyed because I think it will turn people away from our community.”

Scenic outlook and visual amenity are often used in arguments against renewable developments. For some, the sight of turbines or solar panels replacing trees or district views is unthinkable.

In many of the REZ zones, projects are in an early stage of planning, and neighbours and townsfolk don’t necessarily have the experience of living next to a solar plant or wind farm. Can it really be that bad?

Taylor walks over to her kitchen window and looks beyond the garden and farmland and counts the wind turbines on the horizon. She can see seven today, the blades steadily turning on a ridge about 4km away. Far from being affronted by the scene, she loves her view.

“The turbines are really majestic. They’re so beautiful in how they turn so slowly. And on a good sunset they catch the colours and they’re amazing to look at.’’

When the young mother of three moved to Bannister, planning for the Gullen Range Wind Farm was under way. “Knowing that, I and my family chose to buy property and live 1.7km from turbines and raise our three children there,’’ she told a 2015 NSW Planning and Assessment Commission hearing.

Since then, her family has moved even closer after purchasing her in-laws’ home 1.2km from the nearest turbine. The aspect of the house means they don’t see these closer towers but they can hear them. “I reckon once every couple of weeks I may be vaguely aware of them, but it’s not an offensive sound. They sound like the ocean,” she says.

Taylor ticks off the issues causing fear and anxiety in other communities. What about neighbours’ land being devalued? “Around here there is no evidence of any land that has been devalued as far as I’m aware. There’s been plenty of places within close proximity of the wind farm that have sold and their values have gone up just as much as everybody else’s.”

Light pollution from the red aviation lights atop the turbines are a genuine source of annoyance but she says the towers outside her kitchen no longer light up at night.

“It seems that they have to put a red light on for safety and then they go through this rigmarole of the community objecting,” she says. “And then they take them all off. I get that light pollution is really annoying, but every wind farm seems to have them on initially, and then they go.’’

During the construction period Taylor noticed a lot of extra vehicle movement. “I thought they did a reasonable job trying to keep the dust down and things like that, but I did hear quite a few reports of things like gates being left open,” she says. “These are things that just need to be dealt with through proper consultation.’’

Her district is not in a dedicated REZ but anyone driving around here will notice the influx of wind farms on the ridges. The 28ha Gullen Solar Farm is about 4km from her home (“we can’t really see it, only from the top of the hill”) and the high-voltage power lines that form the HumeLink project are slated to run close by.

Taylor – a member of renewable energy advocacy group RE-Alliance – and many other residents have invested in a community-run solar farm with a battery on Goulburn’s outskirts. The way she sees it, the land around here already has been altered. She put it this way to the planning commissioners: “I see roads. I see land that has been cut up into paddocks with fences. I see trees in straight lines. I see a vast number of foreign animals, such as sheep and cows and horses. I see houses with their gardens full of exotic plants.

“That landscape to me is already anything but natural.”

Taylor and her neighbours show that happy co-existence is possible. Across the state, farmers are grazing sheep under solar panels and running cattle under wind turbines while pulling in lease payments that drought-proof their properties.

But nobody is pretending the renewables transition has been seamless. Planning has been poor, communities have been burnt, developers have shirked their responsibilities, projects have been planned in the wrong place, local councils have been left wondering how they can cope with the extra load. Anxiety and mistrust have divided tight-knit communities and detonated generational friendships.

“As is the case with any big change, there are legitimate, valid issues and concerns that people have that need to be worked through,” Bowen has said. He was speaking at the launch of a community engagement review by then energy infrastructure commissioner Andrew Dyer last February and chose the “very beautiful, very productive” town of Bannister to launch the report.

Dyer said that as wind farm commissioner eight years ago he recalled his office working through “heaps of complaints” about the Gullen Range Wind Farm, the turbines that Taylor lives near.

A change of ownership of the wind operation brought better relations with neighbours. “The last complaint we received was closed in 2018, so six years ago,’’ Dyer said. Gullen Range was now a “terrific example’’ of the benefit of doing things properly in terms of community engagement.

Dyer has recently retired from the role but in an interview with The Weekend Australian last April he said much more work was needed to finesse the energy transition. The current development pipeline contained projects that might never progress because they were badly conceived or in the wrong place, causing unnecessary community unrest and bogging down the planning process.

Many country mayors agree. “It’s going to be a bloody train wreck,” is the blunt assessment of Mid-Western Regional Council mayor Des Kennedy, whose local government area is in the Central-West Orana REZ.

The issue with this train is that it’s rattling full steam ahead. There is no stopping it, Coupland says. And he has some blunt advice for landholders who think they can.

“We can probably shape some of it but we can’t stop it. You either have to make peace with that or move, unfortunately.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout