Coast to coast: Australia’s 200km metropolis

One long urban strip is forming as the gaps close between the Gold Coast, Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast.

It begins here, this once-predicted 200km city, at an unremarkable monument on the border of NSW and Queensland. It is a place without fanfare, without the promise of a dazzling future – just four triangles of dreary concrete and a bronze plaque marooned on a manicured traffic island.

Locals and visitors pass between its stiff and angular canopy on the way to the Twin Towns Services Club or Greenmount Beach oblivious to the labours of surveyor Francis Edward Roberts, who etched out the border in the 1860s and whom the plaque honours.

But the Gold Coast – even this southern sliver of it – has never had much time for history. Unveiling the plaque in 1948, Queensland lieutenant governor FA Cooper stated that people did not take “sufficient interest” in the perpetuation of historical events.

How right he was.

Still, this is the Sunshine State’s southern tip, the start of the Gold Coast at Coolangatta, topographically shaped like a ballerina’s crude en pointe, the humble and innocuous beginning of an urban sprawl that spreads north to Brisbane and all the way to another pretty point – Noosa Heads.

Almost 25 years ago, University of Queensland emeritus professor Peter Spearritt made the bold prediction that the state’s southeast corridor – from Roberts’ forgotten memorial to the well-heeled curve of Noosa’s Main Beach – would evolve into a “200km city”, a conurbation along the lines of Greater Los Angeles in the US.

He was right, too.

A 2016 Queensland government draft study predicted that the population of this burgeoning corridor would jump to 5.5 million by 2046. It currently stands at 3.647 million.

But what of the perpetuation of history? What of the past? Would this confluence of the Gold Coast, Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast erase that vast collective swath of treasured memories for millions of people?

Will those flickering moments of remembrance for so many – the family holidays, the childhood interactions with the region’s abundant natural touchstones, the hidden moments, the secret assignations, the living threads that constitute a past – across the past six decades be obliterated by progress? Or stranded, like Roberts’ salt-nibbled brass plaque?

-

A short walk from the border, past The Pink Hotel (a garish retro-restored motel from the 1960s with the motto “a small piece of history in a lively seaside town”), beautiful Greenmount Beach remains unchanged, perhaps the only constant here at the bottom of the 200km city.

The occasional red-brick blocks of apartments, replete with some balcony clothes-drying racks with wavering undies, are dwarfed by a hodgepodge of high-rise apartments competing for water views along Marine Parade. Still, at Greenmount, it’s possible to amble from the grassy foreshore and straight on to the sand.

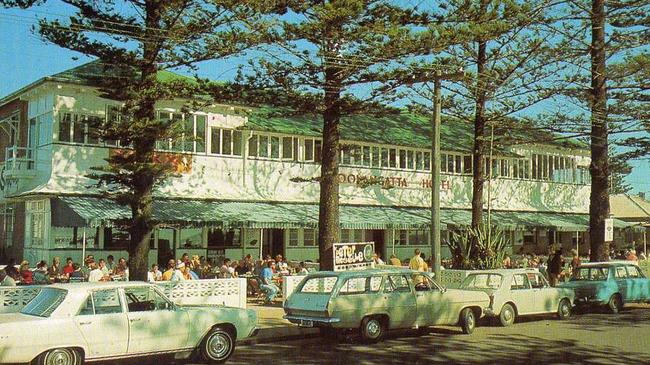

Just north at Coolangatta, the long waterfront strip of pines may be the last antiques of yesteryear. This place, for a time a hedonistic village when hotel pyjama parties were raided by police in the late ’50s, has given way to polished Vespas, to well-to-do ladies walking their groomed pooches and legions of early morning Lycra-fitted walkers, takeaway coffees in hand.

There are a handful of surfers here, dodging traffic with their boards under arm, waxing away in the pine shade, a slender but consistent thread from the past.

Around the bend the Kirra Beach Surf Club (established in 1916) has miraculously survived across a century of change and, with its pitched red corrugated iron roof and yesteryear menu (Sunday special roast of the day – $18), clings to the beachside. It’s a stone’s throw from refined accommodation at the Kirra Beach House (with its Mediterranean-style grazing plates), Aria Del Mare, Nirvana by the Sea and Bilavista Holiday apartments.

Dotted throughout this progress are sporadic clusters of breadfruit and cotton trees which, along with the seafront pines, are the only things you’d recognise in sepia postcards of this place. If you can find any.

For decades this was the quieter, almost forgotten end of the Gold Coast. Not any more.

Farther up Pacific Parade, heading north, are a couple of old Queenslander-style houses, unmistakeable on their stumps with their iron roofs and generous blocks, sitting amid the modern towers like old-timers who have crashed a young couple’s wedding.

Once they would have lined this entire strip, these tin and timber bungalows, generational family holiday homes for stressed Brisbane workers or landlocked graziers from Toowoomba up on the range west of Brisbane city.

Here, memories were built. Tall tales originated. Cherished moments experienced and recalled through whole lives.

But one of these houses carries a real estate SOLD sign in the front yard. And the other looks nervous.

-

In retirement, Spearritt escaped the 200km city that he prophesied and lives quietly in the NSW Northern Rivers region.

He has tried to remain hopeful about the ever-growing conurbation that is South East Queensland. But it’s difficult.

“Vast swaths of new suburban subdivisions continue on both coasts (Gold and Sunshine), all highly car-dependent, so more and more ‘through’ roads have to be added,” he writes in an email. “Green space and environmental quality … (continue) to decline with more and more linear suburban development following the so-called ‘freeways’. More bushland (has been) bulldozed.

“Recent monitoring on water quality in Moreton Bay (is) very depressing, going backwards.”

And don’t talk to him about the 200km city and the current housing crisis. “I will think about a few signs of hope, but the contrast between northern NSW and the Gold Coast becomes ever more stark,” Spearritt writes.

-

It’s not until you hit Palm Beach on the old Gold Coast Highway that you enter what might be called the true Glitter Strip biosphere – that tricky state of mind that tells you that you might be in LA, or Miami, where the roads are straight and long, and on either side are advertisements for flu shots and personal injury lawyers and fitness trainers and nail specialists and health and wellbeing clinics and tattooists and dentists, so many dentists.

Part of that mindset is the need for constant movement. Nothing puts down roots here. Everything can be refreshed, reset, reconfigured to suit the precise needs of human beings at an exact moment.

Another part is desire. Pleasure. For gratification that can be shoehorned into every minute of a vacation. Where past generations came to the Gold Coast to slow down, here, now, is a permanent need for speed.

Except for one place. One small, insignificant postage stamp of earth in the shadow of the majestic Burleigh Headland towards Surfers Paradise. The headland was gazetted as a national park in 1947 and its bushy 27ha make up the only substantial natural reserve between Main Beach to the north and Cooper’s brass plaque on the border. That treasured stamp was, and remains, Rudd Park, a public caravan park that for a couple of weeks each summer through the ’60s and into the ’70s was home to my grandparents and my family.

Here we camped over Christmas, slept under canvas, ate dinner on tin plates on our laps, sitting in a circle on wobbly fold-out chairs. Afterwards, we played cards by lamplight. Or wandered up past the old Burleigh picture house, and my grandfather bought tickets for the Lucky Wheel on the cool bitumen driveway of the local ambulance depot. A rubber ball whirred through a tunnel of small hoops when the wheel was spun, invariably by an ambulance officer in a white short-sleeved shirt, pleated shorts, long socks and leather lace-up shoes.

Here, time slowed down and days were configured by the weather and measured by swims in the ocean or the nearby oceanfront baths and books read and how long it took for huge, cloudy blocks of ice to melt in the Esky.

Today, the caravan park seems to have shrunk. Funky apartment buildings rise on each side of this hallowed, sandy earth. The Burleigh baths building is still there, but not the pool we bobbed about in as kids when the sea was too rough.

That space is now a two-level emporium dedicated to fine food and partying. Below is the acclaimed Rick Shores pan-Asian restaurant, filled as it is with the aroma of roast duck and braised beef cheeks and Korean fried chicken, and not the briny headland of old. And upstairs, The Tropic restaurant and club.

Still, the countless rocks and boulders that hug the crook of the Burleigh shoreline beyond the pavilion remain there, unchanged for millennia. And in the distance, the jagged, unreal, almost sinister skyline of Surfers Paradise.

-

Gold Coast doyenne Regina King, now in her early 90s, was a promising opera singer when she lit out for the excitement of the Gold Coast in the ’60s. Back then, it was “a collection of little villages” before the hoteliers twigged to the place’s potential and it resembled “the beginning of Las Vegas”.

She performed as the only woman in the Moselle All Male Revue (advertised as “Australia’s Top Female Impersonators”). As a financial aside, she started taking photographs of tourists, restaurant diners, celebrities, politicians and business identities.

King continued documenting the Gold Coast with her partner Peter Flowers until a few years ago, and her work has become a historically significant photographic record of the city across six decades.

“The Gold Coast is like a snake that sheds its skin every 10 years, then it sort of reinvents itself and goes to the next stage,” she says. “It’s not blessed with a CBD, like Sydney, and it’s not a seat of state government. It’s just always been entrepreneurial and free enterprise. It’s a very unique place.

“Men like (1980s entrepreneurs and members of the so-called white shoe brigade) Christopher Skase and Keith Williams saw swamp and sand dunes and thought: “OK, I can see something here”, and they just went and created it.”

Leading demographer Bernard Salt has been studying the evolution of South East Queensland (or SEQ as he likes to refer to it) for years and has solid theories about the emerging phenomenon.

“Big Western car-based cities are evolving on the coast (for example, Miami and southern California in the US), as well on either side of the Australian continent,” Salt says. “Other Western car-based communities don’t have the scale or the climate to support this kind of development.

“Plus, given access to a car, to personal freedoms, to an ageing demographic, to a community that is increasingly predisposed to lifestyle and the human preference for sea views, elongated beachside communities in specific locations will continue to evolve.”

He says SEQ cities, towns and villages have “coagulated and fused over time”, and adds: “The old inland towns have been usurped by lifestyle places on the coast.”

Lifestyle. A desire capable enough of driving reasonable human beings to make radical decisions. Here’s one example.

Fifteen years ago, Dani Kaye, 40, from South London, came to Australia on that British rite of passage, the backpacker excursion, and effectively never left.

“It was such a good lifestyle, I wanted to stay,” she says, despite having family back in Britain. After years in Sydney she made the move to the Gold Coast and now lives with her two sons, Charlie, 5, and Zac, 4, in the hinterland village of Mudgeeraba, right on the western fringe of the coast’s burgeoning conurbation.

“My children can go to the beach every day, it’s 20 minutes away,” she says. “They have an adventurous, outdoor life. And the Gold Coast as a city has everything we need.

“Though the village has a lot going on at the moment … trendy bars, fancy restaurants, one of the best bakeries on the coast. It’s a bit of a weird feeling.”

***

The southern end of the 200km city wouldn’t exist if it hadn’t been for those minor topographical obstacles to the west such as the Great Dividing Range and its numerous spurs such as Tamborine Mountain. So, by necessity, it had to expand north towards Brisbane.

In line with Spearritt’s predictions and Salt’s assertions, the coast’s growth, even in just the past decade, has been phenomenal. The suburban creep takes in Oxenford, Upper Coomera, Pimpama, Ormeau and Yatala.

After Yatala, on the M1 (Pacific Motorway), abuts Beenleigh, once the accepted, if not geographically precise, halfway mark between Brisbane and the Gold Coast because of its famous pie stand.

Yatala today is, in every sense, deeply inside the suburban outer rings of Brisbane.

My parents used to talk of a trip from the Queensland capital to the coast taking several hours in the ’50s. I remember it as a trek of 1½ hours or more in the early ’80s.

Now you can reach suburbs such as Pimpama – with kind traffic – in a half-hour to 40 minutes from the CBD.

The Gold Coast, once a destination, is now the southern portion of a greater urban whole, that gruel of sand and skyscrapers and board wax and singing poker machines and the slip-slap of thongs fusing into the capital’s suburban swaths of wooden Queenslanders and corner shops – now groovy cafes and acai emporiums – and deeper to a modern metropolis being reborn into what demographers like to call a New World City.

-

For those of us born and raised in Brisbane, that once-forgotten capital in the backwaters of the Deep North that writer David Malouf called “simply the most ordinary place in the world”, it is today simultaneously almost unrecognisable and, for those native to it, still riddled with private touchstones that are direct portals to its past.

On the M1 heading north, there is a ridge at Mount Gravatt that gives you a distant panorama of the CBD, for decades dominated by the Brisbane City Hall, opened in 1930 and standing at 91m.

The modern vista is stunning, a clutch of business and residential towers captured on three sides by the serpentine Brisbane River. Across that brown waterway, the suburb of West End is also rising with apartment buildings, and it takes no imagination to foresee this mini-metropolis rivalling the CBD across the water.

But dominating the city is the emerging Queen’s Wharf development with its multibillion-dollar casino, residential and hotel towers, and a world-class shopping and dining precinct at the southern end of the CBD’s tongue, an area largely overlooked since the city’s founding in the 1820s.

It may provide Brisbane with its greatest mind shift since Expo 88, the world exposition that unfurled on the city’s south bank at precisely the same time the historical Fitzgerald inquiry into police and political corruption – across the river – systematically dismantled decades of vice and malfeasance and ejected the former regime of long-term premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

And before that, well, surveyor John Oxley stepping from his rowboat in 1823 and declaring the location of the future city.

But here’s the thing about Brisbane. I drive just 10 minutes from “town” into the western suburb of The Gap, and the street where I grew up as a child, and nothing, aside from the height of the footpath trees, has changed. It’s my childhood held in aspic.

The low Besser brick wall my father built in the front yard is still there (albeit with a substantial crack), the letter box is the same, the house ungentrified, and on both sides of the street are neighbours I remember – young and vital back then, with small children of their own, the strains of Petula Clark, Tom Jones and Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass issuing from their radios and record players and spilling down their steep driveways – still living there, now elderly.

In the street where my grandmother lived in Rosalie – a suburb that officially has lost its name, subsumed by neighbouring Paddington, and with views of the towering CBD – there are still ancient Queenslanders high on their termite-proof stumps, their paint flaking and front steps sagging, hanging on between modern, renovated homes like stacks of giant tissue boxes, with their pools and skylights.

In this spruced inner-city enclave, however, when the wind conditions are right, you can still hear the A-flat bells of City Hall every 15 minutes, with the full regal gongs on the hour. For Brisbane people, the vibrations of those bells get into your bones. You know you’re home.

-

Make no mistake – for me and others of my generation Malouf was right. Brisbane was ordinary, and many of us in the ’80s and ’90s fled that ordinariness for a more vibrant future interstate or overseas. But tides do turn.

“There was a time when young Queenslanders made a beeline from BrisVegas, as it was teasingly known by locals, to Sydney or Melbourne or to London and beyond,” Salt says. “Less so today. We’re more likely to hear log cabin-style heartwarming stories of the humble Brisbane origins of, say, the Bee Gees, of Savage Garden, of Trent Dalton.

“Queensland must have been mightily miffed by Taylor Swift denying the Sunshine State a concert of their own. Taylor’s pop-queen successor in the 2030s will make no such mistake: the portals through which Australia communicated globally may have been Sydney-Melbourne over the last 150 years, but from the 2020s forward this nation will have three access points on the east coast: SEQ, Sydney, Melbourne.”

What is far from ordinary is that several major Brisbane CBD infrastructure projects, worth a combined $12bn, will all come online during the next few years.

There’s Queen’s Wharf (at $3.6bn), of course; the Cross River Rail network, a $6.3bn underground metro-style system; and the $2.5bn Waterfront Brisbane precinct on the site of the old and since demolished Eagle Street Pier riverside complex. In addition, there are new pedestrian bridges linking westside Southbank with the CBD and the city’s old Botanical Gardens with Kangaroo Point to the east.

Brisbane, as we know, also will host the Olympic Games in 2032.

Eight years out from the Games, periodic straw polls have indicated that locals are far from enthusiastic about the biggest athletics carnival on earth. They probably will grumble about cost and inconvenience right up until the opening ceremony. Brisbanites, and especially Queenslanders, have never had much truck with history or the future. This is a place unapologetically lived in the present. That may be because of the glorious weather, or the deceptive ease of living in a major city that still has the accessibility and charm of a country town.

But come the hour, they will embrace the moment and wonder what all the fuss was about.

For decades Brisbane remained its “slatternly” (Malouf’s description again) self. Sixty years ago, the population was a humble 678,000 people. Now it has the largest city council in Australia by population and area, with 26 wards that cover 1338sq km. Last year the population of that council precinct was at 1.3 million, with the total metropolitan area exceeding 2.5 million people.

The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics figures have revealed what everyone has known for a while – post-Covid lifestyle considerations and the costs of housing and living have had refugees from Sydney and Melbourne flocking to the 200km city.

Thirty per cent of people on the move last year dropped anchor in Queensland, the bulk of them in Brisbane, the Gold Coast and the Sunshine Coast. Brisbane city picked up an extra 13,452 people. Sydney lost 36,000. Brisbane, out of nowhere, has hurled itself into the 21st century at a pace that has earned it the moniker of the fastest growing capital city in Australia.

Salt says: “Brisbane’s CBD is being reframed by the Queen’s Wharf project, by the Cross River Rail, by the continual improvements to the Brisbane airport. Brisbane has been on a mission ever since Expo 88, I think, which was followed up with several developments in the 1990s that signalled Brissie’s determination to elbow its way into the cosy 100-year-old collaboration which was the Melbourne-Sydney huddle.”

-

It is daybreak in Brisbane and the riverside is teeming with joggers and cyclists. In an hour city workers will be pouring into the CBD from the Captain Cook and Goodwill bridges to the south, the Victoria and Kurilpa bridges to the west, the Story Bridge to the east and via train, tunnel and major arterials in the north.

Some will be daily commuters from the Sunshine Coast and the Gold Coast. Others will be travelling to their jobs in reverse, north and south from Brisbane in this 200km city.

At the foot of the emerging Queen’s Wharf precinct, an intense hive of construction, sits the Commissariat Store (1829), the oldest building in Brisbane alongside the convict windmill up on Wickham Terrace.

-

For decades Brisbane-based writer Raymond Evans, 80, has been one of Queensland’s most respected historians and, aside from his widely praised A History of Queensland, has written diversely on race relations, gender relations and popular culture. He is also a poet.

His family migrated to Brisbane from South Wales in 1949. They settled in a Brisbane suburban street that was “a group of houses planted in the wilderness”. His mother was aghast. Even South Wales had sewerage.

“When I walk around Brisbane now I’m constantly thinking about its past,” Evans says. “There’s all these layers of activities and time periods that occurred. I used to go a lot to those picture theatres and I thought they were wonderful places growing up, and none of them are there any more. You know, they don’t just don’t exist any more.

“I used to go to the Carlton Theatrette, which was under that … it was the Carlton Hotel, which was in Queen Street between George Street and Albert Street, and underneath the hotel was this little theatre where they showed newsreels, cartoons and short subjects.

“You could go in there for about sixpence. You could stay in there as long as you liked. And it was a labyrinthine sort of narrow place, which had little nooks and crannies in it. And you’d go in there with a girlfriend and you could stay in there for hours when you didn’t have anywhere else to go and you could get this little seat that was kind of very private, and you’d be just in the dark with this girl. It was just wonderful.”

He says there was little if any change in Brisbane “forever” and an overriding belief that the City Hall clock tower would always be the tallest building in the city.

“But Brisbane has changed so much. And when you’re in the city today, you just see a different kind of place,” Evans says.

“A friend of mine who lives in one of the outer suburbs, he hadn’t come into Brisbane for a long time and he came in on the train.

“He’s getting older, like me. Anyway, he got on the train and he came down to the city and he couldn’t recognise anything. And he started panicking and he started thinking maybe that the ‘train has taken me to another city’. You know, ‘I’m not even in Brisbane any more’. It was so unrecognisable from the previous Brisbane that he’d known.”

Bestselling author and Walkley award-winning journalist Hugh Lunn, 83, started working for The Australian in 1971. Before that he reported from all over the world, and would go on to write several books including Over the Top with Jim, a memoir of his childhood in Brisbane in the ’50s that went on to sell hundreds of thousands of copies and has never been out of print since its publication in 1989.

Lunn says the disappearance of Brisbane’s traditionally huge backyards and public tennis courts is a sign that Brisbane is on the move.

He says he believes Queensland has “given up all its power” and is now (much like it was after separation from NSW in 1859) a “branch state” of others with wealthier and more influential interests, such as NSW and Victoria.

Not according to Salt: “Melbourne and Sydney had better watch out. A new and increasingly globally recognised city, indeed a fusion-coastal-lifestyle city, is emerging up north. It’s positioned on the green and gold sunny east coast of Australia. Who knew? We knew. We know. A nation of 27 million today heading for 42 million or more in another 60 years, and messily spread across an entire continent, was never going to be contained, to be constrained, by two old, ever-fractious cities, namely Melbourne and Sydney.

“There was, there is and there will ever be scope for another contender, for another big global Australian city sitting proudly, even a tad haughtily, at the centre of a 200km urbanised, lifestyle-infused, coastline that is effectively a new version, a 21st-century iteration of Melbourne and Sydney, and that is shaking off the BrisVegas put-down and is assuming the new mantle of SEQ.

“Get used to it.”

I ask Lunn how much the city has changed across the past 60 years.

“Well, I was in Fortitude Valley the other day – talking about history under our feet – and it now looks like Bladerunner,” Lunn says. “It used to be upmarket with the McWhirters department store and now it sort of looks like how London must have looked like during the Blitz. What has survived is the beautiful weather.”

-

Heading north out of Brisbane on the M1 you can see the great urban push on either side of the six-lane highway. There are Ikeas and Westfields, Bunnings and Maccas. There’s the North Lakes library that is so cavernous and regal it could be out of Alexandria in Egypt. Graffiti covers hoardings separating the thoroughfare from the highway. Behind them, tracts of new suburbia.

Just before the turn-off to Burpengary is a graveyard of old Queenslander houses. A small, empty village of Brisbane’s past, the wooden structures with their pitched corrugated iron roofs waiting to be bought, removed, restumped and renovated.

It’s as potent a symbol as any about the extent to which this part of the world has transformed.

While this portion of the 200km city isn’t as in your face as the Gold Coast, the suburban encroachment is deceptive.

From the air, Burpengary, Deception Bay and Nanango are as good as far northern suburbs of Brisbane, and that spread continues to the north of Caboolture and the foothills of the Glass House Mountains – more than a dozen volcanic plugs in the Sunshine Coast hinterland named by explorer James Cook because they reminded him of the glass furnaces back in his beloved Yorkshire.

There is one, the gorilla-shaped Mt Tibrogargan, that has haunted more than a few generations of Queensland schoolchildren who all experienced the obligatory Sunshine Coast excursions to the Big Pineapple in Nambour and the ginger factory in Buderim.

On the coast, the township of Caloundra has now joined up with Mooloolaba and Maroochydore in the north.

There are numerous forests and reserves that border the highway north to Noosa, but Spearritt’s predictions for South East Queensland have been largely realised. He says even a decade ago “inter-urban breaks” or “green belts” might have preserved the individual identities of the Gold and Sunshine coasts but they are now blurred.

Sitting in heavy but flowing traffic on the Bruce Highway (M1), itself notorious for gridlock-inducing accidents and breakdowns, it’s mildly comical to recall a decade ago Sunshine Coast officials bemoaning the 200km city and rejecting the notion outright.

“We do not want to see the Sunshine Coast become a dormitory suburb of Brisbane,” Sunshine Coast mayor Mark Jamieson trumpeted, as if the phenomenon might be able to be turned back, like the tide.

The Carmody family – Andrew, 61, Liz, 48, and their children Carlos, 18, Ruby, 15, and Roman, 13 – traded life in Brisbane’s inner west for the Sunshine Coast in 2018 and have never looked back.

Brisbane was getting busier and losing its appeal, so they settled in beachside Mudjimba, north of Maroochydore. Suddenly, they went from the madness of the city to a sleepier, more relaxed environment, a place where businesses shut their doors at 4.30pm and tradies, when they turn up, flop about in thongs.

“We all love it,” Andrew says. “It’s quieter and easier.”

They witnessed the real estate boom during the pandemic, and property prices are “double what they were five years ago”, Andrew says. So much so that people from the Sunshine Coast are now seeking out country towns such as Gympie, about 78km northwest of the coast on the M1, for affordable housing.

Is the 200km city pushing even farther west and north?

-

Turn off the highway towards Noosa and there are signifiers everywhere that times have irrevocably changed.

We came camping here too, in the ’60s and ’70s, and the enduring memory of this place of scrub and beach was the unnerving vision of a man in a crude Hazmat-style suit spraying the caravan park laneways with an insecticide to kill the sandflies.

Today the traffic largely constitutes Porsches and BMWs. One personalised numberplate reads CE SERA – “whatever will be, will be, the future’s not ours you see”, so sang Doris Day. There are pelotons of Lycra-clad middle-aged cyclists. It’s as if you’re driving into money.

The region still has its Rudd Parks like the Gold Coast, those ever-shrinking camping sites for the average punters – there’s one on the estuary at Cotton Tree in Maroochydore – but cruising through Noosaville and down into Noosa proper towards the legendary Hastings Street, the luxury villas and apartments that cling to the hill overlooking Noosa Beach, gives you a singular feeling – there are millionaires in the air.

What doesn’t change – like Greenmount Beach down near the Tweed border, and Burleigh Heads, and some of the islands in Moreton Bay and the Glass House Mountains – is the savage natural beauty of this corridor.

Noosa is, in short, naturally magnificent.

Two men are getting massages beneath a billowing canopy just up from Noosa Main Beach on Laguna Bay. Tourists stroll the semi-rainforest towards Noosa Spit, carrying their Frank Green water bottles.

It’s midweek and the cafes and restaurants of Hastings Street are packed. Those same ladies walking their small dogs from Coolangatta are here too, wandering past Gazman and Tiger Lily and Seed and Peter Alexander and Rodd & Gunn outlets. A Rolls-Royce cruises past.

At the bottom of Hastings Street is the Noosa Heads Surf Lifesaving Club. Inside, you can grab a kilogram iced bucket of Mooloolaba king prawns with cocktail sauce ($75) and watch the world go by.

Outside, beyond the club clock that has lost all sense of time, there is a long blue walkway to help you negotiate the sand towards the shore.

And on the shore, here at the very tip of the 200km city (it’s actually closer to 176km, given road changes and improvements since Spearritt looked into the future a quarter of a century ago), you can gaze north, towards the Great Sandy National Park on your left, a 65km unbroken beach that stretches all the way to Double Island Point, and peer into the past.

This is what it used to be. Just the ocean and the beach. Unchanged in millennia. Prehistoric. Primal. The beginning of time.

Until you turn around, get back in your car, and take – on a day of surging traffic to Brisbane, and bumper-to-bumper chaos to the Gold Coast – the almost five-hour return drive to the southern border.

Get used to it.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout