A visionary takes his people back to country

For 60 years, this Martu elder has led his people away from towns and back on to country – dry country – because he understands how the non-Aboriginal world works, and why it often does not work at all for his people.

Muuki Taylor was born at a waterhole called Wayinkurangu in the Percival Lakes region of the Great Sandy Desert. It was around 1945. As a child he repeatedly walked the entire western section of the desert with his family. They travelled in and out of what was later declared Western Australia’s largest national park, Karlamilyi.

In an interview with Inquirer from his home community of Parnngurr, Taylor speaks in his first language – Manyjilyjarra – and his words are translated into English by his young relative Curtis Taylor, an accomplished filmmaker, artist and professional interpreter.

“We were living in our own country; to the west at Karlamilyi is where I traversed the country as a child – where we had bush meat emu, kangaroo and goanna,” Taylor says.

The family also ate kalaru (salt bush or samphire) seeds, witchetty grubs and minta (botanical gum).

Taylor remembers that when they saw an aeroplane, they did not know what it was. They ran and kept quiet in the bushes.

At that point, every person Taylor had ever seen was Aboriginal.

When the first edition of The Australian newspaper was printed in July 1964, Taylor and his family were still living a traditional life in the desert. His people call it pujiman. That makes Taylor a Martu pujiman, revered in the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal world.

Taylor’s knowledge of Martu culture and land is encyclopaedic and rare. He also understands how the non-Aboriginal world works, and why it often does not work at all for his people. He led them away from towns and back on to country in the 1980s during the homelands movement. Living in a bough shed at what is now the community of Punmu, he struck a water bore and helped to build a school and other infrastructure for the other Martu in 1982.

There are now three communities on Martu country – Punmu, Kunawarritji and Parnngurr. They are all dry, by agreement of elders such as Taylor.

As he nears 80 years of age, Taylor can reflect on his achievements, including co-founding a Martu ranger program in 2008 that has become a source of income and pride for families. He did this by establishing Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa, or KJ, in 2008. The organisation employed 513 Martu last financial year – about a quarter of the entire Martu population - as rangers and in other programs.

However, Taylor is not done. He wants to secure the future of the communities he helped to establish. He believes they can and must thrive for the sake of his people.

“Martu, we are at our strongest when we are on our country, far from the troubles of town,” Taylor said in his yearly address to his people, published in the annual report of Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa.

Taylor’s home of Parnngurr is a five-hour drive by dirt roads east of Newman, the mining town built by the Mt Newman Mining Company in the 1960s. Newman is 1200km northeast of Perth. The town is surrounded by mines, including Gina Rinehart’s Roy Hill and BHP’s Mt Whaleback, which at 5km long and 1.5km wide is the single biggest open-pit iron ore mine in the world.

The town is awash with mining money but the town-based Martu are not thriving. No Martu child has ever graduated year 12 at Newman Senior High School. In 2019, the Newman-based head of the local Aboriginal medical service, Robby Chibawe, told police in a sworn statement for the state director of liquor licensing that pregnant women were aware that a baby with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder were born smaller and “we are finding that pregnant women believe this to be a good thing as it makes it easier for child birth”.

“Children aged 12 years and younger are also drinking alcohol, because they are watching their families drink and are trying to get involved with the family,” Mr Chibawe said.

An extreme example of the town’s troubles made headlines in 2021 when an illiterate 17-year-old Aboriginal boy was sentenced to eight years jail for bashing his 18-year-old Martu girlfriend to death with a rock outside a house party in Newman. She had given birth to their son – her second child – a few weeks earlier. The children’s court heard the 17-year-old boy had been a paint sniffer when he was six, was diagnosed with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, had drunk a bottle of Jack Daniels and a carton of beer

on the day of the murder and was in a drug-induced psychosis.

Some Martu families long to leave Newman. They want to take their children to the communities on Martu land – Parnngurr, Punmu (inside the national park) or Kunawarritji – where alcohol is banned and where they will be around elders such as Taylor.

However, housing is in very short supply in each of these communities and the waiting lists are long. Life on their own land is just a dream for them.

In 2023, an audit of the 80 houses across the three communities on Martu land found 40 were “beyond economic repair”. People are living in most of these homes marked fit for demolition because they do not want to move to town.

Taylor is one of them. When Inquirer visited him at his Parnngurr home, the electricity was not working. That meant no airconditioning either.

“They need to fix my house … it’s broken, falling apart. I want a good house like the white people have,” he says.

Taylor, who received an Order of Australia Medal in 2023 for his commitment to his community and for creating Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa, is living the consequences of a decade-long fight between the commonwealth and the states over who should fund remote Aboriginal communities.

The commonwealth officially stopped paying for housing in remote communities outside the Northern Territory in 2018. The states have tried repeatedly to bring successive federal governments back to the negotiating table.

The Aboriginal community of Bidyadanga (population 850) in WA’s north has decided to open up to private investment and private home ownership as a way of solving its housing problems. The Bidyadanga community has been lauded for its decision to declare itself open for business. It can do this because there is a steady stream of tourists passing by with caravans in tow and money to spend. Bidyadanga is a prized coastal fishing spot on a major highway just an hour from the resort town of Broome.

For Parnngurr, circumstances are different. It is not safe to drive there unless in a convoy because sharp rocks on the road routinely destroy tyres. The wrecks of cars that didn’t make it serve as landmarks. When Inquirer went to Parnngurr in convoy in April, tyres blew on two of the three vehicles. The road was dotted with washaways that can bog vehicles. Parnngurr is not on the way to any known tourist attraction.

However, the Martu have plans for an economy. Some of this is contingent on gaining control of the vast Karlamilyi National Park.

As a boy, Taylor and his family followed what is called the Karlamilyi western walking track north to Joanna Springs, then south to what is now the community of Parnngurr – and back again. They did this for years. By the time Taylor reached adolescence, some of his relatives had gone into the pastoral station closest to the walking track – Balfour Downs – and come out again. Taylor’s family had chosen to stay living in the desert.

That changed in 1965 when Taylor’s father Japurtujukurr died, leaving the women, young men and children without their patriarch. They decided to come in.

They walked to Balfour Downs. By then, Jigalong Mission had been operating for 18 years just outside the Martu’s traditional lands. Jigalong had been a workers’ depot for men building the Rabbit Proof Fence. In 1947, the state government gave permission to the Apostolic Church to start a mission at the former depot for Aboriginal people.

In the 1960s, it was practice that the nearby station owners phoned Jigalong Mission and told them when a group of Aboriginal people had arrived from the desert at their station.

The mission then sent out vehicles to pick up the group.

In a photograph taken of Taylor’s family group being collected from Balfour Downs, he is present but obscured by Aboriginal men in white shirts and cowboy hats. Those men were already living and working at Jigalong and were able to speak to Taylor’s family about what to expect.

The passage of time and the quality of the image has made it difficult to identify everyone in the picture, but the women in the photo are thought to be Taylor’s two mothers Ngalyatanta and Jali Jali. The non-Aboriginal man is Pastor Denton.

It is an extraordinary record of a time when the commonwealth did not and could not make laws for Aboriginal people. This was explicitly forbidden in the Constitution until 1967, when Australians voted emphatically to allow the commonwealth to enter Indigenous affairs. Until then, states made their own rules. In WA, British-born bureaucrat Auber Octavius Neville shaped official policy towards Aboriginal people from 1915 until his retirement in 1940. He believed in “breeding out the colour” and said so in his book Australia’s Coloured Minority: Its Place in the Community. Taylor’s family was subject to none of this while it was being rolled out. Neville had been dead for eight years when Taylor’s family left desert life behind for Jigalong. However, Neville’s effect lived on variously. In 1972, one in 10 Aboriginal people in WA were living in institutions. Most were children.

Taylor recalls his people’s exodus from the bush. “When we were children from there, the old people were here in the country then all left to Jigalong,” he says.

“We lived there as children pujiman times – no flour no white people.”

Taylor and some of the other young men in his family group did not go into the mission school system or dormitories, as Martu children did. Taylor worked for about a year at the Jigalong mission then went almost 450km north to work on Yarrie station, a 250,000-hectare rangelands property north of the Pilbara town of Marble Bar.

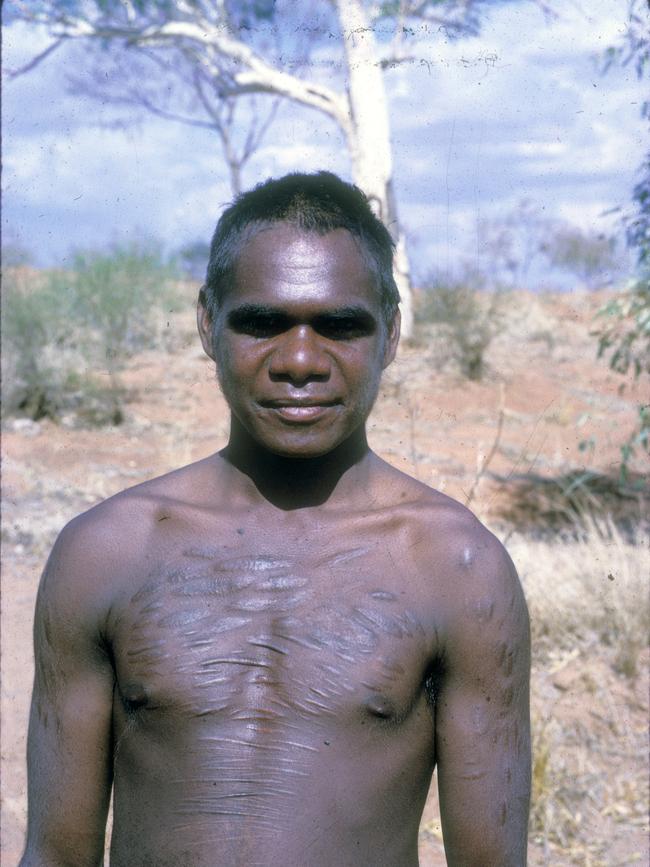

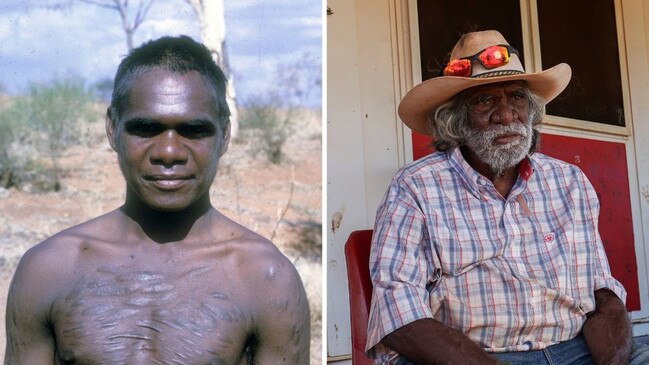

A photograph of Taylor not long after he left the desert for Jigalong shows him bare-chested with tribal markings across his torso and arms. He gives the photographer a closed-mouth smile. He is lean, strong and literally a picture of good health. Taylor worked in the pastoral industry for about 15 years after this picture was taken, including for a decade at Warralong station, which employed many Martu men in a co-operative organised by non-Aboriginal activist Don McLeod.

After that, Taylor and other Martu moved back to their traditional lands to create the communities he cares so deeply about.

After helping to build Punmu, he moved to Parnngurr in the 1990s. He knew Parnngurr and its rock hole before he even knew there was a non-Aboriginal world.

“Yes this home (Parnngurr) is good that water place to the south is name Parngurr from pujiman (bushman) times the old people called that name Parngurr before they passed,” Taylor tells Inquirer.

Martu woman Darilyn Peterson considers herself fortunate to have been offered a chance to move to Parnngurr. She brought her sons Kirk and Reshayden.

“Parnngurr the community and the people in it – it’s amazing. And the older people here. Older people, younger people get along together how it is supposed to be,” she says.

“Parnngurr, it’s like free and open. It’s like bring your spirit, you know – lit up. It is more peace and quiet.”

The local school is another important reason Peterson wants to stay in Parnngurr. Word has got around among Martu parents that children want to be at Parnngurr Community School. Attendance is around 90 per cent. Children who could not read are learning new words daily.

“The principal and teachers here are very nice,” Peterson tells Inquirer. “They welcome you and since my baby been here, my little one Kirk and Reshayden my oldest … it’s beautiful.”

Principal Prem Mudhan arrived at Parnngurr five years ago with his wife Jennifer. They both have PhDs – his in education and hers in arts and culture. Jennifer is in charge of the curriculum and reading daily with students one on one.

One of her most successful ideas is a wall chart of the Oxford word list that runs horizontally along the full length of a wall. Vertically, each student’s name is printed down the left hand side of the chart. When a child learns one of the words on the list, they get to place a tick underneath that word in their column.

Initially, Jennifer was concerned that parents and students might not feel good about how public the list was.

“But everyone loves it,” Jennifer says. “Children want to see the data wall. Parents want to see the data wall and they are so pleased when they see how many words their child knows.”

The results speak for themselves. Inquirer has been to remote schools where students do not sit the NAPLAN tests because they do not have the English skills to comprehend the questions. However, at Parnngurr, there has been steady progress.

Year 5 students are now reading at what educators call “national level to cohort reading age”. In other words, they are not only sitting NAPLAN, they are passing.

At Parnngurr, year 3 students’ NAPLAN results showed that they reached the minimum achievement level for numeracy.

NAPLAN has become a celebration at Parnngurr. After students sit their test, everyone has cake.

Jennifer and Prem know the school is giving primary school aged students a good start to their education. They speak regularly to parents about how best to help students through their final years of high school.

The Martu have come up with their own solution – a mini-hostel in Newman with 24-hour care for students.

Liam Limbie and Jacquyn Butt smile when they’re asked to give a meanness rating for their hostel housemother.

“Twenty out of 10,” says Liam, laughing.

“One hundred,” says Jacquyn. He adds: “Nah.”

They are teasing Sharon Greenwood, one of the staff at a small hostel where the boys stay during school term in Newman. This is a bold experiment on the verge of success. She is among workers for contractor 54 Reasons and is responsible for enforcing the hostel’s 8pm bedtime rule on weeknights. They do not love that, though they like her.

Liam and Jacquyn are months are away from being the first Martu to complete high school at Newman. There are three Martu teens in the hostel who are in year 12 and they are all on track. Martu elders believe it is in large part because of this small hostel that they planned for a decade.

The hostel is in east Newman, the suburb where the first generation of town-based Martu mostly live. There are 11 students currently staying there in years 7 to 12. Staff take the students to sport in the hostel minivan, and take them fishing on weekends.

Sometimes, they will drive them home to their remote communities for important cultural events, and then bring them back.

Liam is from the former mission of Jigalong, east of Newman. The road to the community is sealed as far as the Roy Hill mine turnoff then it is dirt. He says he has found school work hard at times.

Jacquyn agrees; his closest relatives are in Parnngurr, about six hours by unsealed road northeast of Newman. Jacquyn says the thing he misses most about home is being able to talk to family face to face each day. Liam agrees, and says he misses his dogs too. They say the upside of hostel life is privacy – each student has their own room – and games. The staff at the hostel know more about COD Fortnite than they ever thought possible.

Liam and Jacquyn are each working towards goals that feel close. Liam will go to Kapooka after graduation and train with the Australian Army.

When the school year ends for Jacquyn, a talented Australian Rules footballer, he has a full-time job waiting for him with desert sports entity Ngurra Kujungka. That is the organisation responsible for the annual Martu footy and softball spectacular played barefoot in the dirt. This month, about 600 Martu and talent scouts are expected to watch the carnival at Parnngurr.

“At the end of the day it’s all worth it,” Liam says.

The Martu people are not wealthy compared with some other Pilbara Aboriginal groups. There are no iron ore mines on their traditional lands. Much of Martu country was declared a national park more than 40 years ago, against their wishes. But the Martu have cleverly managed what they do have with help from a board that includes independent directors.

The Martu formed their own corporation – Jamukurnu Yapalikurnu – and have struck deals with exploration companies looking for nickel and other minerals around the remote desert communities where the have lived for millennia. This is how the Martu can afford to contribute to the hostel. It is not cheap to run. The funding comes from Jamukurnu Yapalikurnu and the Cook government, with contributions from mining companies.

Jamukurnu-Yapalikurnu chair Bruce Booth, a Martu man, says the Martu student hostel has been a wonderful success so far. “We’re all incredibly proud of the young Martu people who are dedicated to reaching their goals,” Booth says.

“This project wouldn’t have been possible without the tireless advocacy of the Martu parents who understood what their community needed and worked hard to make it happen.

“We’re also grateful to BHP and the regional development minister, who listened to Martu and funded this project to allow Martu students to continue their education while remaining strongly connected to their family, culture and ngurra.

“Our students deserve enormous credit for their hard work so far, and the Martu community stands strong behind them. In turn, they are an inspiration to the many future Martu kids who’ll be able to follow in their footsteps thanks to the hostel.”

We cover the nation

Coast to coast: Australia’s 200km metropolis

One long urban strip is forming as the gaps close between the Gold Coast, Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast.

Out of towns and back to country: Visionary leads his people

For 60 years, this Martu elder has led his people away from towns and back on to country – dry country – because he understands how the non-Aboriginal world works, and why it often does not work at all for his people.

Farmers put their livelihoods on the Line

George Goyder’s Line was the one certainty farmers could count on in a heartbreak land where dust devils dance among the early settlers’ broken dreams. But what happens when even that constant fails? Can human ingenuity and perseverance hold out against climate change?

Renewables ‘biggest change since white man turned up with sheep’

The land will be vastly altered: solar panels on the flats, wind turbines on the ridges and new high-voltage towers connecting it all, but the residents of these towns have more pragmatic things on their minds than rural scenery.

Should you give up your salmon to save a species?

Logan Saltmarsh is worried. But it’s not schoolwork or bolshie big kids unsettling this 12-year-old; it’s Tanya Plibersek. In fact, the whole town of Strahan is on edge.

Life in Australia’s most multicultural suburb

Not quite the Truman show, in this town educated families live in big houses, send their kids to new schools, push babies around in pram brigades and literally dance in the streets.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout