Parents’ challenge ‘morals’ dilemma of religious school legal reforms

State ‘morals’ limitations on faith-based education institutions run counter to the most basic protection of the family unit against state indoctrination.

Last year the Albanese government set in process what is shaping to be the most fundamental reform of the law impacting religious schooling this country has undertaken since the enactment of the Sex Discrimination Act in 1984. The Australian Law Reform Commission has been charged with drafting laws that will ensure a religious school “must not discriminate against a member of staff” but may “continue to build a community of faith by giving preference … to persons of the same religion”.

Given the exercise of a preference for one person necessarily entails the refusal of another, there is a clear tension between these two requests. Whether the ALRC can reconcile that tension will determine the future of authentic religious schooling in this country.

The initial direction the ALRC has taken in its consultation paper holds out little prospect of attaining that reconciliation. The ALRC argues that generally accepted “morals” within the community should now prevent religious schools from requiring staff to model or faithfully teach their religious employer’s precepts. It asserts that community morality on matters of sexual conduct has so fundamentally altered in a progressive direction that the government can now limit religious freedom under what is described in international law as the “morals” limitation ground.

Put crudely, religious institutions with a traditional sexual ethic are “immoral”. Rather than signifying progress, this contention is more redolent of fourth-century Roman emperor Maximinus Daia’s direction that the burgeoning Christian “cult” should be “driven from your city … so that it may be purged of all … impiety”.

Setting aside the factual question of whether community morals have so changed, international human rights law sets out the broad framework of a principled resolution. Contrary to the ALRC’s argument, the lodestar principle is that state limitations on private schools operate as a gauge of a society’s wider regard for individual freedom. This is because private religious schools give effect to “the liberty of parents … to ensure the religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions”, quoting Article 18(4) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of 1966.

As the Australian Human Rights Commission has acknowledged, unlike the general protection to religious freedom the “parental right” is so fundamental to liberty that it is not subject to limitation. The European Commission on Human Rights has recognised, “the principle of the freedom of individuals, forming one of the cornerstones of society, requires the existence of a possibility to run and to attend private schools”. The fundamental relationship between private schooling and democratic freedom was disclosed in the commission’s criticism of the Swedish government’s excessive regulation of private schools, which it said encumbered the “guaranteed … right to think freely”.

The commission warned that “Swedish schoolchildren are in principle led to think only in the directions that are decided by the political majority of the parliament”, with the government “seem(ing) to regard the right to keep a school as something entirely within “le fait du Prince” (the fiat of government power)”. The right to private schooling is essential to democracy precisely because it restrains the state from surrendering to the siren call that would have it indoctrinate forthcoming generations into those majoritarian values not shared by their parents. This is the very tension the ALRC now presides upon.

Almost 50 years before the Bolshevik Revolution, Fyodor Dostoevsky warned of the potential for state-imposed Utopian visions to become totalitarian. In The Devils, he analyses the psychology of the early Russian socialist movement of the mid-19th century. He was well placed to offer such an insight, having been subjected to a mock execution on order of Tsar Nicholas I for being a member of a revolutionary cell in his youth. Through the character Shigalyov, a subsequently enlightened Dostoevsky dissects a political philosophy willing to sacrifice “a hundred million heads” to achieve the “future form of society right now”. In his enthusiasm Shigalyov unwittingly declares: “Beginning with the idea of absolute freedom, I end with the idea of unlimited despotism.”

Dostoevsky’s answer (spoiler alert) to this augury of Utopian brutality was as astounding for its simplicity as it was for its brilliance. He concludes his 700-page analysis of revolutionary psychology with a simple unadorned account of the birth of a child. His profound insight was that the reply to universalist Utopian ambitions is a reaffirmed confidence in the timeless capacity of parental love as nature’s (Dostoevsky would say God’s) unsurpassed means to cherish the coming generation. It is the very realisation of that parental capacity through private schools (a confluence affirmed in human rights law) that the ALRC now holds within its gift.

However, as the European Commission of Human Rights has recognised, the autonomous ability of religious bodies (including schools) to retain staff who can convey their identity “is indispensable for pluralism in a democratic society”. These freedoms are not in the gift of the state – they are fundaments of a free and open society. Herein lies the resolution of the tensions within the charge put to the ALRC. As human rights law recognises, in a free society there may be legitimate forms of distinction that will not breach the right to equality. Where a religious school selects staff to retain its religious ethos and thus give effect to the religious and moral convictions of the parents it serves, it does “not discriminate”. The considered reform model released in 2019 by the ALRC’s immediate past president, Justice Sarah Derrington AM, honoured that principle. The ALRC would do well to return to Justice Derrington’s work.

Last month the NSW government referred the exemptions for religious institutions and religious schools to the state’s Law Reform Commission. Both the Western Australian and Queensland governments have recently announced their desired reforms. They will implement an “inherent requirements” test similar to that adopted in Victoria.

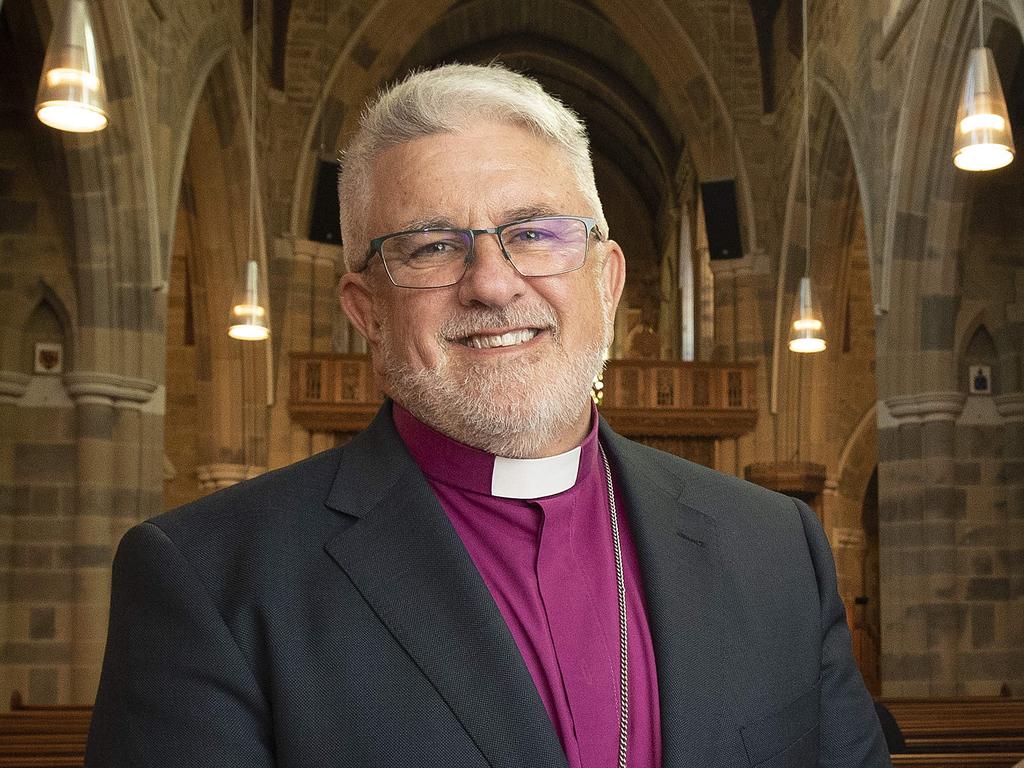

That law seeks to limit the ability of a church or mosque to require that all staff hold and model the faith of their employer. This directly impacts their ability to maintain a distinct institutional ethos. Victorian law also limits the ability of such bodies to require that their leaders effectively model their beliefs. For example, it is no longer certain that a covertly married Catholic bishop or an Anglican bishop “caught in sin” could be stood down where they were repentant. This is because the law seeks to prevent an institution from acting in respect of non-religious activity in an employee’s private life. A religious institution may only act in respect of inconsistent beliefs. This is plainly contrary to the settled consensus within human rights law.

The Victorian legislation also now requires all faith-based institutions and schools to satisfy the state that their religious actions are “proportionate” and “reasonable”. Both tests are notoriously imprecise and fact-specific, conferring upon judges an extraordinary granular discretion over the affairs of religious institutions. Moreover, this power operates over matters of religious practice, where personal judicial convictions as to what is “proportionate” and “reasonable” may vary significantly. Indeed, owing to its ill-defined nature, former Australian chief justices Murray Gleeson and Robert French have separately recognised that what is “reasonable” is something upon which judicial minds may “differ”. Victorian law creates inequitable uncertainty for both institutions and employees. It does not provide an acceptable model of reform.

The ALRC has also been requested to provide recommendations for reforms that would “ensure” faith-based schools “must not discriminate against a student on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, marital or relationship status or pregnancy”. Considered reflection on the full effect of this deceptively simple request is required. As the British government has acknowledged, “schools with a religious character” must “have exceptions (in anti-discrimination law) for how they provide education to pupils” in order to maintain their distinct ethos.

The following examples illustrate the kinds of conduct a school would need to satisfy a court were “reasonable” or not “on the ground” of a protected attribute were the existing exception to be removed:

• A student who is not heterosexual complains that the teaching of a school’s traditional view of marriage is discriminatory.

• A school adopts a policy that students must use the facilities that correspond to their biological sex.

• A school tells a group of students they cannot operate a club that exists to advocate for the school to eschew its religious beliefs concerning marriage.

Notwithstanding the decrease in religion seen in the recent Australian census, with Christians for the first time in a minority, parents are increasingly entrusting the education of their children to schools with a religious ethos. The Independent Schools Australia 2022 edition of the School Enrolment Trends and Projections Research Report found “over the past five years, the independent sector has seen an average enrolment growth rate of 2.3 per cent per year which exceeds overall student population growth over the same period (1.2 per cent), followed by the government sector with 1.1 per cent”.

Christian schools within the independent school sector grouping are displaying extraordinary growth. Christian Schools Australia’s director of public policy, Mark Spencer, states: “The growth in enrolments across member schools … was 14 per cent from 2021 to 2022, an increase on the already high 9 per cent increase in 2021 from the previous year.” The reason for this growth? He argues that with 74 per cent of parents indicating that teaching of traditional Christian values and beliefs was extremely, or very, important “there is clearly a strong desire for education built on strong and explicit values and beliefs”.

If community morality has changed, as the ALRC now asserts, these parents haven’t joined the movement.

Parents are preferring religious schools as a means to instil religious and moral values within their children. What the ALRC has been asked to determine is no less than whether this most basic protection of the family unit against state indoctrination, this “right to think freely”, will continue to be honoured in the formation of coming generations.

Mark Fowler is principal of Fowler Charity Law and an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Law School of the University of Notre Dame Australia, and an Adjunct Associate Professor in the School of Law at the University of New England and a Research Scholar at the Centre for Public, International and Comparative Law, University of Queensland. This extract is based upon an address provided to the Sydney Catholic Business Network.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout