Celibacy and service: unexpected calling for the new generation of Catholic priests in Australia

What would possess a young man to join a church battered by scandal, fractured by the pull of modernity and so diminished in the West? Go inside the very personal journey into priesthood.

God will find you in the strangest of places. For Isaac Falzon it happened in the unseemly confines of a toilet off the factory floor where he earned just enough to blow on partying and playing up at the weekend. In that searing moment of clarity – call it an epiphany – he found himself kneeling beside the pedestal utterly bereft, at a loss to answer the questions that were going round and round in his head like a stuck vinyl record. Is this it? Is this all there is to my life?

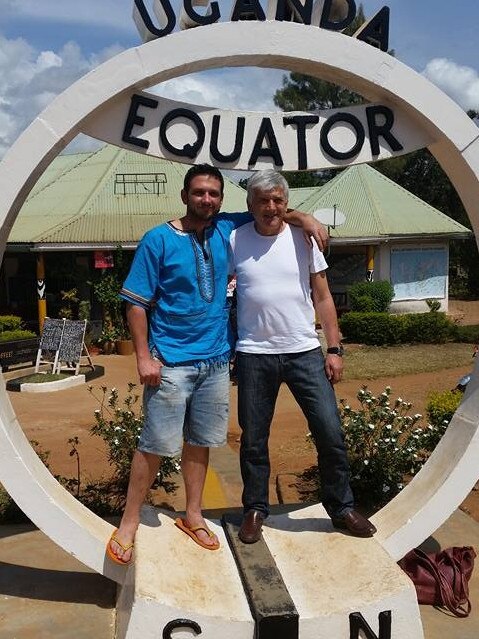

The answers didn’t come in a blinding flash; there were no heavenly peals, no voice from the burning bush. It took time for Falzon, 36, to realise his vocation was the Catholic priesthood, and even then he wasn’t sure where the journey would take him or whether he should be on it at all. So he took things one step at a time. He went to Uganda with his dad and crisscrossed Australia on a youth mission to understand what God wanted from him. He prayed and studied his Bible, as well as the textbooks he had put away after being expelled from school for the second time in year 10. “I was a bit of a bad boy back then,” he says sheepishly.

He sat for a makeup exam to gain mature-age entry to the Australian Catholic University in Brisbane, where he joined four other first-year novices at the Holy Spirit Seminary. Falzon didn’t think he would make it through the opening weeks of 2017. “I didn’t know what a full-stop was when I turned up,” he remembers. “On my first day, after lunch, I sat on my bed and almost cried, thinking, ‘What have I got myself into?’

“And I decided, ‘Oh well, I’ll stay until Easter and then leave if it doesn’t work out, because at least I would have given it a go’. But Easter came along and I was enjoying the work, loving it in fact, and I started to realise that maybe I had found a place in this community. I was doing well in my assignments and making friends and everything just kept falling into place.

“So I stayed until the end of the year and then I decided to come back and engage in year two. And by the end of the third year I said, ‘OK, this is going well so maybe the priesthood is a viable option’. It was, like, I could finally see myself living this life, which was definitely not the case when I went into the seminary. I never thought I was going to be a priest at the end of it; really, it just didn’t cross my mind. I entered the seminary to engage, essentially, in what I had to offer.”

But here he is on the eve of his ordination with the other two graduating seminarians of the Class of ’23, Gerard Lai, 29, and Minje Kim, 33 – clever, hardworking, well-educated young men who probably could have done anything they set their minds to, but who instead chose a chaste and selfless life of service to God and their future parishioners. They’re the hope of a Church that has been battered by sexual scandal, diminished by Western society’s growing indifference to organised religion, and outargued in the village square on articles of faith such as same-sex marriage and voluntary euthanasia for the terminally ill.

As newly-minted priests, they will confront an uncertain world, cloaked in the grey of moral ambiguity. Yet there will be no going back once they enter Brisbane’s St Stephen’s Cathedral together to make time-honoured vows of obedience to their bishop. No regret, either, for what they must forego as men of the cloth: marriage, children, material wealth. In a culminating act of the ordination rite, all three will lie facedown, prostrate before the altar, while the congregation gives stirring voice to the Litany of the Saints, one of the Church’s oldest and most revered prayers, set to a mesmerising Gregorian chant.

What do they expect to feel in that deeply moving moment? “Joy,” Falzon says simply. “For me, my entire life was really in search of love, meaning and purpose and it took me a while to understand that I didn’t have to find them, they found me through God and my relationship with Jesus Christ. So when we stand up I think we will feel the Holy Spirit washing over us, elevating us into this new state of being. And in that moment, I will be giving thanks to God for the gifts and protections that he has given me.”

Lai says: “Laying there on the top step of the Sanctuary is … a symbol of surrender, a symbol of giving your whole life to God and the people of God through the vocation of the priesthood. This part of the service, the Litany of the Saints, is where you ask all the angels and the saints for their guidance and their protection and for their intercession to pray with you and for you that your ministry may be fruitful.”

Adds Kim: “To me, this means saying ‘yes’ to the mission Jesus has given me. Which means I can’t be lazy, but I can be more confident of my ability to carry it out and keep my promise that I will do God’s mission for the rest of my life.”

To take a snapshot of who is entering the Catholic priesthood in Australia today you could sit this trio down and click away. Kim, born and raised in the port city of Busan near the foot of the Korean peninsula, is emblematic of how the Church has had to look to Asia, Africa and Latin America to fill the yawning gaps in the ranks of an ageing clergy. Lai is the son of Malaysian immigrants from working-class Logan, south of the Queensland capital, who initially trained to be a biologist. Falzon, like them, is the first in his family to become a priest.

Each was immersed in the faith from a young age, but they all struggled with doubt and temptation before finding their way. In a very real sense, the outcome was never preordained. The six-and-a-half years they spent at the seminary was a proving exercise for both parties – Church and novice. The last thing anyone wants is a conflicted priest.

The institution they’ve pledged themselves to is supposed to be in crisis, not only from two decades of reputational damage inflicted by child sexual abuse and other priestly scandals. The numbers tell the story. The five million Australians who identify as being Catholic were served in 2021 by a 2900-strong clergy comprising 1834 general or diocesan priests assigned to a given parish or locality and 1066 priests belonging to religious orders such as the Jesuits and Franciscans. This was down from the 1971 peak of 3895 priests, a 25 per cent fall-off according to recent research for the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference. (In addition, there are about 220 ordained deacons, some of them priests-in-waiting.)

This is hardly a Catholic-specific issue, of course: the Anglican Church of Australia, among other mainstream faith communities, is equally pressed. But celibacy is seen to be an added disincentive to becoming a priest of Rome when it’s not mandated by the Eastern and Orthodox cousins of the Latin Church, let alone Protestant denominations. Pope Francis, for a time, seemed prepared to explore whether the requirement should be dropped, and the issue was kicked along in 2019 after an extraordinary Vatican synod on the Amazon recommended that the ban on married priests be lifted in remote parts of the South American region to address a dearth of clerics there. The late “pope emeritus” Benedict XVI, who stood aside in 2013 to pave the way for Francis’s ascension, came out strongly for priestly celibacy, crushing the push for change. The pontiff blinked.

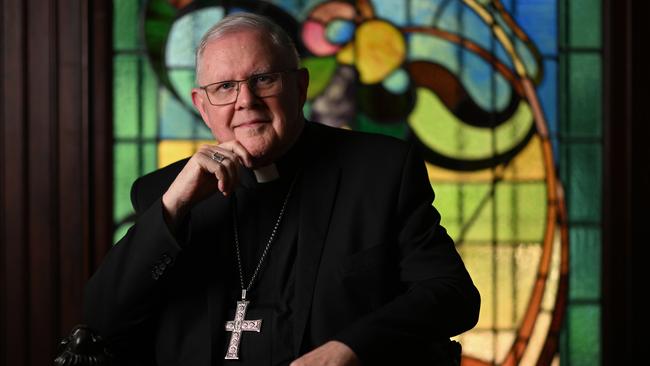

That was far from the end of matter. Whatever the rights or wrongs of sexual abstinence – and we’ll get to that with the Class of ’23 graduates – debate in and outside the Church continues to bubble along. As we report in The Weekend Australian, Catholic Archbishop of Brisbane Mark Coleridge has proposed that celibacy be waived for Indigenous priests to bring more First Australians into the fold, a variation of the Amazon theme. As the immediate past president of the Australian Catholic Bishops’ Conference, Coleridge has heft in the Church’s high councils. His prediction that mandated priestly celibacy is “highly likely” to be abandoned down the track should and will be taken seriously. “I don’t know quite when or how but … the question is certainly not going away,” he says. “And I think there will come a point of maturation when it will look kind of like the natural next step, not an artificial or dramatic or untimely overturning of what’s been a very long tradition.”

Still, another part of the equation is often overlooked. As well as a shortage of priests, there’s the problem of empty space in the pews. Only 11 per cent of professed Catholics regularly attend mass, according to new figures from the National Centre for Pastoral Research, down from 15 per cent in 2001. That gives a ratio of one priest to every 226 churchgoing Catholics, says University of Western Australia academic Philippa Martyr, who has crunched the data. “This is nowhere near crisis proportion,” she insists. “In fact, I would argue the situation is quite manageable.” The catch is that the ratio blows out between city and regional areas, where there are far fewer priests. “So what we have is a clergy distribution problem, not a clergy numbers problem,” she adds. “We will probably run out of laity before we run out of priests.”

And contrary to the received wisdom, the number of men entering the Catholic priesthood in Australia – and remember, they can only be men – appears to be holding after dropping precipitously in the 1960s and ’70s. Since the turn of the century, 546 priests have been ordained nationally (432 of them in a diocesan capacity), according to the Catholic Church Directory. Some 304 men were in training as of 2021. Martyr says this conforms to the 1990s’ average of roughly 25 ordinations a year. While the median age of priests is rising in line with that of their parishioners at 63 years, Martyr says there is a corollary to declining church attendances: those who continue to go are deeply committed, especially if they’re aged below 30. “There’s a groundswell of younger, conservative churchgoing Catholics on the move in Australia,” she says. “That’s where a lot of these vocations are coming from.”

Gerard Lai is a case in point. His parents, Edmund and Cecelia, are teachers who met at university and rarely missed mass on Sunday with their three kids. Growing up, he played soccer and ran cross-country; he didn’t think of himself as being overly religious. God was a comforting presence in his life at high school, not a focus, until he and his sister were invited to a Catholic youth camp. He wasn’t doing much over the holidays so why not?

Between the canoeing and surfing, Lai got to thinking about his faith, of taking it for his own instead of dutifully going along with mum and dad to church. He made his confession to a priest and was astonished by how good it made him feel. “I honestly felt lighter,” he remembers. “I felt God had forgiven me and I went from knowing about Jesus to actually knowing Jesus … that he wasn’t this guy from 2000 years ago, he was present here and now and he could be my friend who I could converse with through prayer and reflection.”

A light bulb went on for the young man. He travelled the state with the Catholic outreach program NET Ministries before heading to the Queensland University of Technology to undertake a science course, aiming to become a research biologist. He had a girlfriend and enjoyed a “full life” on campus. But there was this nagging sense he couldn’t shake that his life’s purpose was elsewhere. Lai moved into Canali House, a former Catholic presbytery given over to young men considering the priesthood, where he completed his degree. Entering the seminary in 2017 seemed like a natural progression. “It felt like it was where I was supposed to go; I felt at peace,” he says.

It turned out to be a seismic year for all the churches. Australian Catholics were rocked on June 29, 2017, when Victoria Police announced that George Pell would be charged with a string of historic sex offences against boys, some of which were withdrawn ahead of trial. The late cardinal rejected the allegations but was eventually convicted and jailed for assaulting two 13-year-old choirboys in Melbourne’s St Patrick’s Cathedral during the 1990s, then freed by the High Court, acquitted on appeal.

Rumbling along in the background was the fraught question of same-sex marriage. On December 9, 2017, parliament gave effect to a nationwide plebiscite vote to legalise such unions, piling pressure on priests of all stripes to bless them in church ceremonies. A handful of Anglican ministers did, but the Catholics held the doctrinal line that the sacrament of marriage was the preserve of a man and a woman.

Less than a week later, on December 15, the marathon Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse delivered its final report, which was particularly scathing of the Catholic Church. Some 7 per cent of Catholic priests who had served in Australia between 1950 and 2010 were accused of preying on children; 309 matters relating to abuse in church-run or aligned institutions would be referred to the police by the inquiry, resulting in dozens of prosecutions.

And in Victoria, the dust was still settling on the passage of a voluntary assisted dying law to allow terminally ill patients to legally seek medical help to end their lives; within five years every other state would follow suit. Around the same time, the holdout jurisdictions of Queensland, WA and NSW decriminalised abortion. Hallowed tenets of faith, doctrine and trust in the churches were teetering at every turn and there was no escaping the fallout, not even in the contemplative quiet of Holy Spirit Seminary.

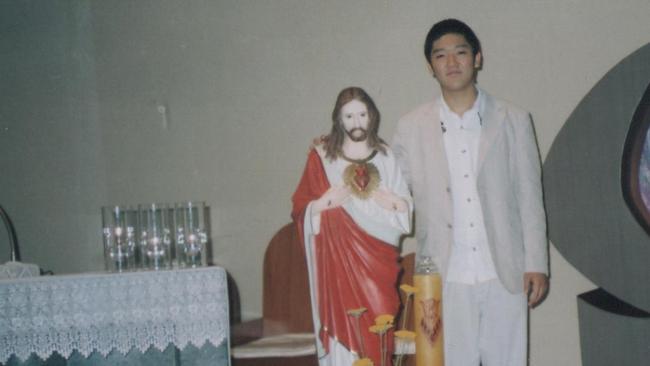

Minje Kim had intended to be a bus driver until he packed a bag and set out to see the sights of Australia in 2016. His Catholic family was something of a rarity in predominantly-Buddhist South Korea, as was their deep commitment to the Church when educational and material advancement was the accepted marker of achievement. An altar server from the age of 10, he was at first intrigued by how the priest imitated the role of Jesus.

But then his father, Jangsoo, lost his job as a hotel concierge during the global financial crisis of 2007-08 while his mother, Hyunsook, developed heart disease. Young Kim was at a loss to understand why God would allow such things to happen to good people, grappling with a dilemma that has occupied theologians through the ages. (The answer, he now says, is complicated: “We don’t know much about God’s opinion or idea on that because we can’t. We are human beings, we have a finite presence, whereas God is like infinity, almighty.”)

Kim found himself slipping away from the Church. He stopped going to Sunday mass for a while, but he couldn’t stop thinking about his “friend”, Jesus. He was a shy boy who didn’t have much to do with girls, though he liked the idea of having a girlfriend. Instead, he concentrated on high school and gradually his faith returned. He went on to study social work at university and worked as a parish youth minister. He wasn’t entirely convinced there was a future in that, though.

Kim knew what he wanted to do with his life: he wanted to help people. The tricky part was how. He sought out a priest he trusted and poured out his heart. The kind man enquired whether he had heard of the Camino de Santiago, the pilgrims’ way that starts in the foothills of the Pyrenees in southern France and winds across northern Spain. Christians had travelled the trails for centuries to find themselves, the priest said. Kim was intrigued.

He walked all 800km and somewhere, somehow, his doubts fell away. God’s presence pervaded the verdant landscape, dotted with rustic stone churches. He reached the last official waypoint at Santiago de Compostela and opted to push on to the sea at Camino Finisterre – a kind of metaphor for what was to come in his “continuous journey” in the priesthood. “I felt like God was saying, ‘You will not stop walking … you will continue to walk with me on your own pathway,’” Kim remembers. “That was my big insight, my big learning.”

The details still eluded him. It wasn’t until he landed in Australia in 2016 that the pieces fell into place, and a vacation turned to vocation. The vibrant mission culture in the archdiocese of Brisbane captivated him, leading him to apply to Holy Spirit Seminary. It wasn’t easy: Kim’s rudimentary English took a lot of work to begin with. But he persisted. He had found what he was looking for – meaning to his life.

So had Isaac Falzon. We’re talking about that rock bottom moment in the toilet in 2015, when he was 28, how in his wretchedness he had asked God for a sign, a word, anything. If you’re real, Lord, show me. I need you. “It just hit me. I knelt down next to the toilet seat to say a prayer … you know, basically just asking what was my life about? Was this all there was?” he says. “It wasn’t like anything happened. There wasn’t this big earthquake scene. But there was a gradual healing. I think it was because I needed my words to confess what I always knew in my mind: that I was not here to do the things that I was doing at the time.”

Falzon hadn’t returned to school after he was shown the door in year 10. He’d gone to work as an apprentice cabinet maker, and pushed trolleys of snacks around the ’Gabba stadium on weekends to earn extra cash. One day, he was assigned to a corporate box; it was the easiest money he had ever made. So Falzon quit his day job and went into hospitality, kicking around the world while waiting tables, picking up bar or catering jobs. And he enjoyed a “full life” – that term again – with girlfriends, some of them committed relationships.

Was he tempted to marry, and perhaps start a family? “The thought crossed my mind,” he says, carefully. “It was just that … settling down with someone was never a peaceful decision I could make.” As a boy, one of three kids, the only time he could remember missing mass on Sunday was when their dad ran over the family cat. Falzon was back in Brisbane in 2016 when his father mentioned that he was going to Uganda for a Catholic leadership conference, and invited him along.

There, Falzon was struck by the simplicity with which people lived and loved God. “They didn’t have physical things like us, but they had all this peace and joy and happiness and community … and I realised this was what I had been looking for,” he recalls. “I came to realise that all my life I had been searching for love. But in Uganda, I came to realise that it was love, God’s love that was searching for me. All I needed to do was open my eyes.”

He sold his car on returning home and volunteered for NET Ministries. But he knew he couldn’t do that forever; that “little bubble”, happy though it was, couldn’t last. Someone gave him a book, To Save a Thousand Souls, US priest Brett Brannen’s guide to discerning a vocation in the Catholic clergy. It struck a chord with Falzon. He began to think about becoming a religious brother – they number just 608, alongside 3501 religious sisters, according to the Australian Catholic Directory – or maybe even a priest. Suddenly the idea didn’t seem fanciful.

Neil Muir was one of 16 in the Class of ’93 who went through the old seminary before it was repurposed as the scrubbed-brick headquarters of the Australian Catholic University’s Brisbane campus. The 58-year-old priest is now the rector at Holy Spirit, a scaled-down operation set in a tranquil corner of the hilltop site.

He’s also the last man standing from his graduating group; the rest left the priesthood, often to marry. Celibacy is the first thing that high school students raise when he talks to them about his vocation. Not in the niceties of romance or parenthood, either. They want to know how anyone could live without sex.

It’s a good question for our soon-to-be priests. Kim alone is willing to discuss his dating history – given he professes to not have one. “No, never,” he says when asked if he’d had a girlfriend. “I was not confident to approach girls, I was super shy.” Lai says it’s inevitable that they will experience sexual attraction as priests. That’s not the point, he explains. It’s how you deal with it. “You acknowledge it. You acknowledge it internally but you don’t do anything about it,” he says. “In a way, it’s similar to being married and seeing an attractive human: you acknowledge it and then you move on because you’ve made a commitment in your marriage to be faithful. The same goes with us. You have made a covenant to love the people of God and to serve the Church. And that’s going to be your way of life – you’re not going to devote your love to one person, you’re going to devote your love to God’s people, all people.”

Note the neutral language. It’s a nod to the jam that gay marriage created for the churches and the underlying issue of same-sex attraction. The Catholic position is convoluted, to say the least. In effect, it is permissible to be homosexual provided you don’t act on that desire – a similar standard, in other words, to priestly celibacy. Yet is it fit for purpose in an increasingly secular society? In response to the Royal Commission into child sexual abuse, the Church’s Truth, Justice and Healing Council conceded that “obligatory celibacy” may have contributed to the offending by predatory clergy. And there is nothing in the Bible or Christ’s teachings demanding priestly abstinence: St Peter the Apostle was married, after all. The case against celibacy is that it’s not just impractical but unnatural, a driver of aberrant behaviour among some priests.

Falzon, Kim and Lai know the arguments: they went through them in their own minds while weighing up whether to take the cloth, and again and again in class and group discussions at the seminary, in solitary prayer and contemplation. Yes, they concede, to forego the love of a spouse or children is a sacrifice. But it’s a necessary one for the Catholic clergyman. Falzon points to a famous exhortation by Pope John Paul II in 1992, the Pastores Dabo Vobis, that celibacy is the priest’s “gift of self in and with Christ to his Church,” words that would be echoed by the current pontiff. The young man continues: “When people think about intimate relationships the mind automatically seems to go to the sexual aspect. But that is only one part of a true relationship … it’s the other parts that we find so fulfilling … the love you get to experience between people that’s non-sexual, that’s a service and life-giving. So the vow of celibacy is that your whole heart, your whole mind, your whole body, your whole soul goes into this ministry of love to your people.” Or as Lai puts it: “There’s more to life than sexual relationships. You can definitely live a very fulfilled and wholesome life through this vocation and there’s more, so much more greatness to it.”

Muir says the dropout rate from their intake of five – 40 per cent – is fairly standard. His experience suggests that at best only one of the three will be wearing the Roman collar on reaching his age. “It’s full of challenges,” he says of the life of a priest. “Overall there’s joy, incredible trust and reliance on you, more than what I thought I could give sometimes.” In his time as a seminarian, up to 60 candidates would have been in training at any given time through years 1-7; today, Holy Spirit has 15 seminarians on the books, one of whom is on “discernment leave” pondering his future. The emphasis was more academic back then, focused on doctrine and theology. The course work is still demanding – graduating seminarians emerge with a Master’s qualification and, in Falzon’s case, a basic degree as well – but equal weight is given to the human and pastoral elements of priestly “formation”, where they’re likely to trip up later.

Muir says applicants are carefully vetted. Many would have spent time preparing in a semi-ecclesiastic setting such as Canali House before applying to the seminary. He prefers that they’ve also lived a bit, had a career and a life outside the Church before committing to the priesthood, like he did. Muir was 28 when he left the seminary after studying accountancy and working for a bank. (“I was bloody hopeless at both,” he laughs.)

Before being accepted, each candidate undergoes lengthy psychological evaluation and must pass a selection board numbering Muir, a senior religious sister, a second veteran priest and psychologist. If the local bishop signs off, they’re in. Narcissistic tendencies or “propensity to sexual deviancy” are grounds for immediate disqualification, Muir says.

At Holy Spirit, seminarians live four to a shared cottage, do their own laundry, clean, shop and cook for themselves. The idea is to keep them in touch, Muir says. The seminarians receive practical guidance on dealing with the dilemmas they will confront as priests: never be alone with a child or vulnerable young person; don’t linger in the room with the altar servers before or after mass, they’re taught. Once ordained, they will be paid a “stipend” of $425 a week. No one is in it for the money.

“It’s an interesting balance that I think we, as new priests, need to find,” Falzon says. “Essentially we need to be in the world, but not necessarily of the world … the priesthood is witness to a different option to materialism, to cynicism, even in today’s day and age. It’s that other place of refuge that people can turn to and be accepted.” How do they feel about the reputational damage the Catholic Church has suffered? “It’s simply a tragedy, it really is, especially for the victims,” Falzon says. “And as with all tragedies, there are consequences. Part of my job as a priest going forward will be dealing with that.” Kim admits being nervous about what the future might hold. “A pilot doesn’t know when turbulence will happen, but they know how to cope with it, right? That’s their training and in a different way, that’s our training as priests … We believe that Jesus comes to us not only in good ways, but through our challenges too.”

The world isn’t going to do them any favours. Take Voluntary Assisted Dying, a diabolical proposition for the churches. Archbishop Coleridge, who is to preside over their ordination, has warned that sections of the last rites could be denied to those taking up voluntary euthanasia, depending on the person’s attitude to the Church’s teachings on the sanctity of life. “That does not mean that the Church can’t offer pastoral care, can’t surround the person and his or her family with prayer,” he emphasises.

The rites in question are the sacrament of Viaticum – Holy Communion for the dying – and the concluding Prayer for the Dead. Lai says he’s given a lot of thought to what he will do when asked to attend someone undertaking VAD. “I think we need to show love and mercy towards the person,” he says. “Who are we to deny someone the sacraments – that is, the gift of Jesus Christ himself? Let God do the judging. So I would probably give Viaticum.”

Falzon nods in agreement. “I would give them mercy, yes.”

Their time has finally come. It’s June 29,a date marked down in the Christian calendar as the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul in memory of the martyred apostles, and there’s barely standing room in St Stephen’s. People mill in the entrance and side galleries of the packed cathedral, hunched against the evening chill.

In the Catholic tradition, this is a favoured occasion to ordain priests. The three young men walk side-by-side down the aisle in their white alb tunics, the red sash of the deacon’s fascia slung left to right across their chests – they were admitted to the first rung of the clergy six months ago. The position of deacon, incidentally, is as far as a married man can go in terms of advancement in the Catholic Church. There are married priests, too – former Anglicans and other defectors who switch sides, a little known loophole in the celibacy mandate. One such priest is on hand for the ceremony, which has brought out just about every priest in the Brisbane archdiocese, and some from overseas as well. The families of the three ordination candidates fill the first two rows beaming in their Sunday-best outfits.

Twenty centuries of Catholic pomp and mystique are on show: incense floats in the air like pungent fog, the choir is in spine-tingling voice. Coleridge wears the bishop’s peaked mitre headdress and carries a gold-tipped crosier, the ceremonial shepherd’s crook. He asks the young men in turn: “Do you promise respect and obedience to me and my successors?”

“I do,” each of them replies.

They prostrate themselves on the marbled floor of the sanctuary, hands folded beneath the chin, as the Litany of the Saints begins. The congregation is kneeling to pray, heads bowed. Holy Mary, Mother of God, the choirmaster intones. Pray for us, people respond. St John the Baptist – pray for us; St Joseph – pray for us; St Peter and St Paul – pray for us … and on the roll-call goes, through to Australia’s own St Mary of the Cross MacKillop.

Falzon, Kim and Lai rise to their knees. Coleridge lays his hands gently on their heads in turn, blessing them. The rest of the priests in attendance – all 120 of them – follow suit before the Prayer of Ordination is said.

The young men’s journey is complete. They climb to their feet to don the robes of their new office, the stole and crimson chasuble, lovingly attended by their parents. For better or worse, in sickness and in health and mostly for the poorer, they are now priests of the Roman Catholic Church. That is their sacred vow – as binding as any marriage can be.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout