Churchill’s secret weapon in the fight to save civilisation

Chartwell was more than a retreat; there, the man who became Britain’s wartime PM gleaned insights into events in Germany.

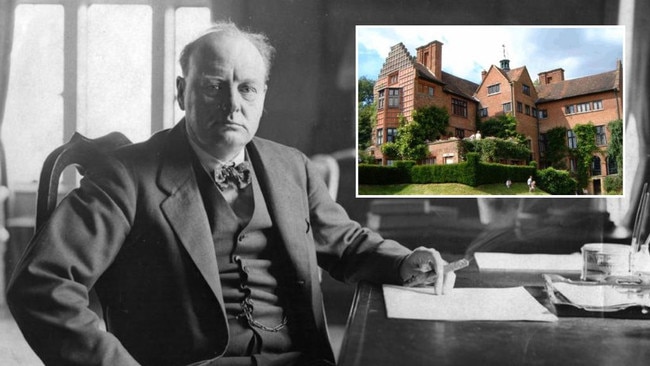

When you arrive at Winston Churchill’s country home, Chartwell, near Kent in South East England, you understand why he was captivated by it.

As he looked out across the ponds to the woodland and rolling green hills that touched the horizon in the distance, he felt this was truly England. It was the view, not the house, that he fell in love with.

He purchased Chartwell in September 1922, not only as a retreat from busy London but also to work, plan, organise and strategise, and to relax and entertain. It constantly needed repairs, though, and would be a drain on his finances.

When you enter through the west-facing grand oak front doors, you step into the hall and lobby with Lady Churchill’s sitting room to the right and the library to the left, and the large drawing room at the rear. Upstairs were bedrooms and bathrooms, and Churchill’s study. The east-facing dining room on the lower ground floor has yet another stunning view.

Churchill, clad in a siren suit with Cuban cigar in hand, would take to the grounds of Chartwell to walk and think, to paint landscapes from a portable easel or work from his detached studio, indulge in one of his favourite pastimes, laying bricks, and to tend to his menagerie of fish, ducks, swans, hens, goats, pigs, cats and dogs.

“A day away from Chartwell is a day wasted,” he said.

Katherine Carter, curator of Chartwell, examines the pre-war period in Churchill’s Citadel. She chronicles some of the remarkable visitors from Albert Einstein and TE Lawrence to Charlie Chaplin, HG Wells and Joseph P. Kennedy, and even China’s ambassador Quo Tai-chi, as the storm clouds of war gathered and Churchill was charting a political comeback.

“It depended on who was visiting and the timing, but certainly a considerable number were invited in order to glean insights, particularly about events going on within Germany,” Carter says. “He was very lucky to have a number of individuals who had fled from Germany who could bring their own perspectives.”

The meetings Churchill convened were about learning what was happening in politics, diplomacy and the military at home and abroad as much as it was about persuading people of his view: namely that the threat posed by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime had to be confronted rather than appeased. A vivid early warning about Hitler came from Einstein’s visit in July 1933.

One of the most important visitors was Heinrich Bruning, who had been German chancellor before Hitler and had since fled the country in May 1934, fearing for his life. Months later he was at Chartwell, with Churchill probing him for information. He visited again, including in August 1937, when the German danger was even greater.

“He was able to bring not only information from his context in Germany, in some instances he was able to bring fellow guests who had been victims of the terror playing out,” Carter says of Bruning. “This was in a climate when so many political figures were keen to acquiesce to Hitler’s territorial ambitions.”

A mix of flattery, persuasion, encouragement might be employed depending on the guest. Sometimes these meetings did not go to plan if the guest did not see eye-to-eye with the host.

Ambassador Kennedy was a case in point. He was effectively an appeaser, whom Churchill failed to win over to his point of view.

“Some of these meetings didn’t go his way,” Carter says.

“Joe and Rose Kennedy were seeing friends and acquaintances around London who were very deferential. Churchill is in complete contrast to that. He goes straight into campaign mode and sees an international threat that perhaps if America and Britain work closely together they can mitigate that risk. That doesn’t land well with the Kennedys.”

At Chartwell, Churchill would work until late and rise early, first with a glass of whiskey, and begin giving orders to staff. He would command from his bed, then the bath, and from around the house. Memos were written, telegrams responded to, letters sent. “Action This Day” would often be affixed to important documents. He would nap late in the afternoon to energise him for evening activity.

A visitor for the day or overnight would witness Chartwell’s particular routines that played out in different rooms at different times such as sherry before dinner, often a meal of French-inspired cuisine, and cigars with brandy or port after dinner. Churchill drank excessively, Pol Roger champagne was a must for lunch and dinner, but he was rarely seen inebriated. His constitution was legendary.

“If you were invited to Chartwell, you were potentially someone who could be of value to Churchill,” Carter says.

“It was in his interest to make you feel comfortable and welcome because he wanted your support. Over dinner, Churchill would be charismatic, offer his views, encourage debate and discussion, and it would be a really fun evening.”

Carter lived at Chartwell for a period, in the original servants’ quarters in the attic, providing an opportunity to experience the house and grounds in all seasons and at different times of day. “At the very top of the house, you get the view at its most extraordinary,” she says. “There were times when I would get up early to watch the sunrise and it is among the most beautiful sunrises in the world.”

Churchill would not have become Churchill without Chartwell. “We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us,” he said. It was here that he could live life to the fullest, indulging in his passions and pursuing his destiny. His finances were so badly managed, as he routinely overspent and had to find income quickly to pay the bills, that Chartwell was actually put up for sale in February 1937.

“What Chartwell gave to the Churchills was a remote location where meetings could be held away from the prying eyes of Westminster,” Carter says. “It is these meetings that put Churchill in the position of knowledge and authority on the subject of Nazi Germany to be brought back into government. If Chartwell had been sold, it might well have impacted considerably on the course of history.”

When Churchill’s decade in the political wilderness was over and he returned to cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty in September 1939, he relocated mostly to London. When he became prime minister in May 1940, the risk to Chartwell from German bombers was high and the countryside home was largely shuttered for the duration of the conflict.

Walk along the grounds, stroll through the rooms and take in the atmosphere, and the place still breathes Churchill. It houses about 9000 objects – furniture, pictures, books – that were owned by the family.

Today it is presented as it was in the 1930s, when it played a seminal role in shaping the man who would, more than any other individual, save democracy.

Churchill’s Citadel: Chartwell and the Gatherings Before the Storm by Katherine Carter is published by Yale University Press.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout