Bipolar disorder is crippling, but it has given the world moments of sheer brilliance

Some of the world’s greatest geniuses have suffered bipolar disorder. A Sydney psychiatrist wants to add Winston Churchill to the list. His evidence? The Antwerp siege on October 3, 1914.

In the early months of World War I, as the Germans advanced deep into Europe on two fronts, British war correspondent Joseph Mary Nagle Jefferies found himself in the besieged Belgian city of Antwerp.

The British had poured troops – including sailors and marines fighting offshore – into the defence of Antwerp to delay the German advance towards France, where German troops would be poised to attack Britain. Taking charge of the British defence was not any General but Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, the civilian minister for the Royal Navy. Churchill, later to become one of Britain’s greatest prime ministers, was a

Sandhurst graduate who had served in north west India and the Sudan War, before leaving the Army as a Lieutenant. What Churchill lacked in military rank in Antwerp, he made up for with a self-belief that many in Whitehall regarded as a kind of megalomania bordering on insanity.

Amid the chaos of the Antwerp siege on October 3, 1914, as vehicles jammed against each other in the streets, horses reared and ambulances entangled with ammunition wagons, Jefferies observed a dashing individual he described as flamboyantly dressed in a “flowing dark blue cloak with silver lion-head clasps”, wearing a yachting cap, climb atop a platform and begin directing traffic in the manner of an orchestra conductor, yelling out commands in what was described as a crazy mixture of English and French. Another witness described later observing Churchill regarding the chaos of the battle under a rain of shrapnel, “tranquilly smoking a large cigar”.

The siege of Antwerp held back the German advance for only a few days, yet Churchill regarded that feat as an outstanding success. The British press thought otherwise, excoriating the politician as a posturing military adventurer who had exposed untrained men to grave danger. Psychiatrists also have taken an interest in the disconnect between the pandemonium of Antwerp and its dubious status as representing any kind of military gain, on the one hand, and the grandiose conviction of Churchill that the battle had virtually saved England.

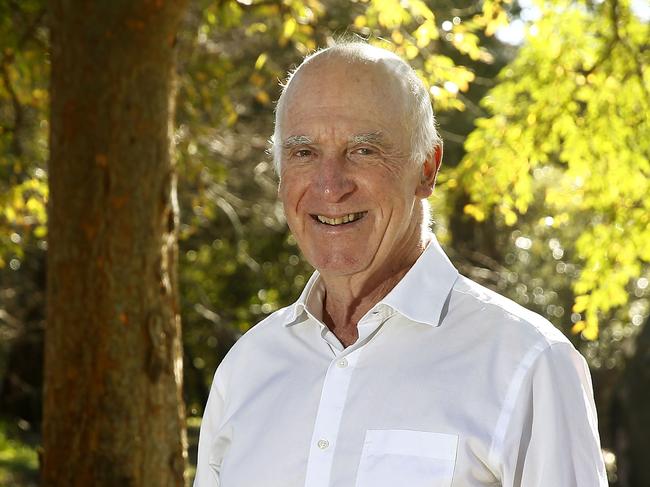

Gordon Parker, Scientia professor at the University of NSW, has analysed Churchill’s wartime record through the lens of psychiatry and has written a play about him. He believes the well-known legend of the curse of the “black dog” – an expression coined by Churchill to describe his debilitating bouts of melancholia – in fact were part of a more complex mental health condition no better exemplified than by the wartime leader’s behaviour at Antwerp.

“You could say that Churchill was incredibly courageous and grandiose and that he became alive when bombs were dropping around him, and therefore that’s all an expression of his personality,” says Parker, who practices as a psychiatrist in Sydney. “But I feel the Antwerp incident takes it beyond that because of the bizarre behaviour, standing there, directing the troops like a traffic cop, dressed like a lion tamer, being exhilarated by that experience, and then making contact with the king to say that he wants to be put in charge of the armed forces. Now, there is no logic to that. I think it takes it beyond the issue of a narcissistic or entitled personality.

“Antwerp is the best example I can find of Churchill’s entitlement, rashness, impetuosity and grandiosity that goes way beyond his station. And I would make the case that Churchill was bipolar.”

It’s not the first time Churchill’s depression has been reassessed as bipolar disorder by psychiatrists.

In the book Downing Street Blues: A History of Depression and Other Mental Afflictions in British Prime Ministers, American psychiatrist Jonathan Davidson writes that Churchill was described by those who knew him as larger than life and “not in the least like anyone you have ever met”.

Davidson writes that Churchill’s “limitless energy, creative ideas and immense volatility” are strongly suggestive of bipolarity, and that some associates had remarked on his frequently “crazy state of exultation”. He points to Churchill’s documented tendencies towards belligerence, overspending, his enormous energy and prolific creativity (Churchill was the author of 43 books in 72 volumes), and combative style of interpersonal relationships.

“Churchill’s chief of staff, General Ismay, described him as a person who could not be judged by ordinary standards, who was either on the crest of a wave or in the trough, highly laudatory or bitterly condemnatory,” Davidson writes.

“His moods were as variable as the April day. He was notorious for his disdain for other people and their opinions, and his unwavering belief in himself as a great man.”

Davidson concludes that Churchill did not exhibit the full-fledged manic episodes associated with classic bipolar I disorder but showed features of hypomania when he displayed unusually high energy, elevated mood, irritability, impetuousness and elevated judgment. These episodes often were followed by crippling depression.

Bipolar disorder – which has two iterations, bipolar I with cycles of manic episodes and depression and bipolar II characterised by hypomania followed by depression – is defined as involving at least three of seven symptoms that must be present for a minimum of four days: inflated self-esteem and grandiosity, reduced need for sleep, excessive talkativeness, racing thoughts, distractibility, increase in goal-directed activity and excessive involvement in pleasurable activities with potentially harmful consequences. The disorder is often manifest in profligate spending, alcohol binges or increased libido.

Davidson concludes following his analysis of 51 British prime ministers that 15 per cent of the leaders displayed evidence of mood disorders, 19 per cent anxiety disorders and 35 per cent abused alcohol. Six former British prime ministers could be classified as falling along the bipolar spectrum – Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, Benjamin Disraeli, David Lloyd George, William Pitt the Younger, William E. Gladstone and Churchill.

“In the case of the war leaders Pitt, Lloyd George and Churchill … all three possessed a Messianic belief only they could save their imperilled country,” Davidson writes.

The overrepresentation of mood disorders among prime ministers and presidents – Davidson’s findings about British leaders were reflected also in his earlier analysis of the mental health of US presidents – throws up intriguing questions as to why such high-functioning, highly intelligent and talented individuals may be disproportionately affected by mental health disorders such as bipolar.

Some believe these individuals’ tendency towards mania or hypomania and the extraordinary energy that comes with it propels them towards extraordinary achievement; others point to some evidence that suggests a correlation between high IQ and bipolar disorder.

A cohort study by British and Swedish researchers of a million men published in 2013 in the journal Molecular Psychiatry attempted to interrogate the long-held anecdotal and biographical reports that have suggested bipolar disorder is more common in people with exceptional cognitive or creative ability. They found men with the highest verbal or technical ability had a higher risk of hospitalisation with pure bipolar disorder.

The scientists said their findings “provide partial support for the belief that exceptional intelligence and a particular form of ‘madness’ are linked” and was “in keeping with biographical reports linking bipolar disorder with exceptional literary or scientific creativity”.

History abounds with brilliant individuals and creative geniuses who suffered bipolar disorder – notable examples are Leonardo da Vinci, novelist Henry James and comedians Spike Milligan and Robin Williams.

And it is the connection with creativity that many scientists believe is the strongest link between intelligence and bipolar disorder.

“The connection between bipolar disorder and intelligence is an area of interest but the findings haven’t been consistent,” says Scientia professor and psychiatrist Philip Mitchell, who leads the genetics of bipolar disorder study at UNSW.

“But there is this intriguing relationship with bipolar and creativity and high performance.”

Parker points to extraordinary phenomena in individuals in a manic or hypomanic state, including suprasensory changes. Heightened senses of smell, taste, vision, touch and hearing have been well documented and are strongly linked with enhanced creativity.

Parker has written in the scientific literature about these suprasensory phenomena in his patients, and says heightened perception sometimes extends to “increased percipience, with individuals observing that they are more astute in judging people, in seeing patterns in data, or in reading micro-expressions of people and non-verbal interpersonal nuances”.

He also is intrigued with the phenomenon of “bipolar eyes”, first observed by Scottish psychiatrist Alexander Morison in 1840. Parker describes seeing in his own patients that when they were in an elevated mood state they sometimes displayed “sparkling eyes – where the eyes are bright and there may be a shimmering quality and dilated pupils”, and, rarely, even colour changes. He cites scientists who have linked the phenomenon with the increased norepinephrine levels in manic and hypomanic states that may cause changes in pupillary size.

The upshot is while bipolar disorder can be disabling, it can also drive individuals to great heights of success and achievement.

“These individuals are capable of great brilliance, but it also comes with a lot of risk,” Parker says.

Reframing mental illness through a lens of the complexities and richness of human experience, rather than one of reductive pathology, is the key not only to greater understanding but also acceptance and appreciation that while mood disorders can plunge people into immense darkness, they may have also played a part in giving the world some of its most significant advances in sport, business, politics and artistic brilliance.

As Parker’s homage to Hamlet at the top of one of his scientific papers attests: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

Gordon Parker is undertaking a study of people who have been diagnosed with bipolar disorder in the last one to five years. He is researching the effectiveness of differing medications that they may have received. If you can assist in completing the survey, it can be accessed at https://bit.ly/bipstudy Any information provided will be completely anonymous.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout