Letters stir up ill-founded palace intrigue

The long-awaited release of the Palace letters should have closed the story on Gough Whitlam’s 1975 dismissal, but a new culprit has emerged: the Queen.

The long-awaited release of the Buckingham Palace letters should have closed the story on Gough Whitlam’s 1975 dismissal, yet full exposure of the historical record reveals this dispute will never die and that a new culprit has emerged — the Queen and the palace.

This is a tribute to the mood of the age: the triumph of post-truth and phony history over factual and documented history. On the central issue, the documents are unambiguous. They confirm the Queen was not forewarned of Sir John Kerr’s dismissal of Whitlam. She was not an authorising agent, complicit in a conspiracy, nor had any tacit understanding with the governor-general.

This had always been known and accepted by the three towering figures at the heart of the crisis: Whitlam, Kerr and Malcolm Fraser. They never subscribed to a conspiracy theory implicating the Queen and the palace. They understood this was a uniquely Australian crisis and a clash of towering personalities.

This reality cannot be denied. The dismissal was a monumental train wreck in its prelude, execution and consequences. A surprise dismissal in an ambush was a highly unsatisfactory outcome. The real attitude of the palace documented page after page in this voluminous correspondence is best summarised by a remark once made by Kerr’s predecessor, Sir Paul Hasluck: “The wisdom of constitutional monarchy is to avoid confrontation.”

Our political culture, however, has been stained by an immature impulse to blame outsiders for what happened. For decades, the myth persisted that the CIA was behind the dismissal and, in the past few years, a new myth has arisen — that the Queen gave Kerr the “royal green light”.

There was never any evidence to sustain this. This week’s release of the letters should have provided the concluding judgment. Everything is on the table. For most observers, the documents are explicit. As the Queen’s private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, wrote to Kerr on November 17: “I believe that in NOT informing the Queen what you intended to do before doing it, you acted not only with perfect constitutional propriety but also with admirable consideration for Her Majesty’s position.”

But the palace did play an informal role. With dismissal at the heart of Fraser’s strategy, being raised by Whitlam several times in conversations with Kerr, and repeatedly appearing as an option in Kerr’s correspondence, Charteris had a firm message for Kerr in his November 4 letter: the reserve powers should be used only “when there is demonstrably no other course”.

In short, the palace preferred delay. It wanted every other course to be pursued first. It wanted a political settlement of the crisis short of dismissal.

A week before the dismissal, the palace viewed the crisis as “political” and not “constitutional” which could require vice-regal intervention.

Yet this week’s reaction from the Labor Party and the Australian Republic Movement reveals the depth of the attachment to the belief that the palace and the Queen behaved improperly and deceptively, with Labor saying the Queen “was advising the governor-general on how to remove our elected prime minister” — a statement that is false on any available evidence.

The republican attack on the Queen and the palace was a diatribe of confusion and fabrication and included the ludicrous claim that “without the explicit assurances of the palace, Sir John Kerr may not have acted”.

Writing as opponents of Kerr’s dismissal of Whitlam and as republicans who strongly supported the 1999 referendum, it is dismaying to see misleading narratives about the Queen’s complicity injected front and centre into this debate. This is because, first, they are wrong and, second, because they will only damage the republican cause.

The irony is that Whitlam and Fraser, both supporters of the 1999 referendum, did not implicate the Queen in the dismissal to advance the republican cause.

The republic can succeed only by appealing to a wide range of Australians. Without bipartisanship, it will be permanently denied. The issue for the republic is not the Queen’s behaviour, since she has been a monarch of diligence, integrity and popularity. By trying to make the role of the Queen and the palace in 1975 an argument for the republic, Labor and the republicans are engaging in misrepresentation that will permanently doom their cause.

Interviewed this week by The Australian, the Queen’s assistant private secretary at the time, Sir William Heseltine, made it clear that the palace would have preferred a political settlement, with Kerr delaying the dismissal. Asked how the palace would have responded had Kerr requested direct advice on future action, Heseltine said: “I suspect the advice that would have been given to him was that it would have been prudent to hold off a little bit longer.”

This is consistent with Heseltine’s earlier interviews with the writers. He said: “It would be fair to say, however, that both Sir Martin Charteris and myself felt that it was a pity that this very drastic solution was applied exactly when it was and that a little bit more political leeway would have enabled a political solution to emerge.”

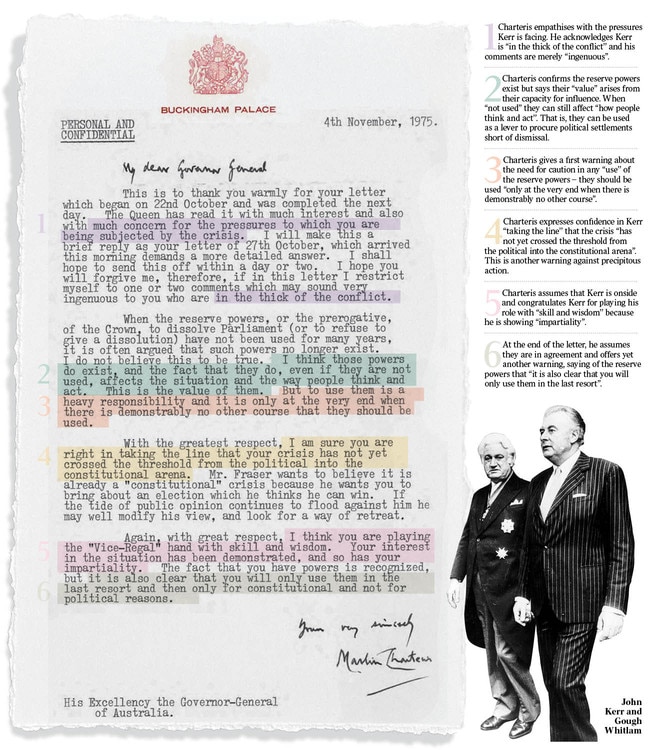

This position is evident from Charteris’s November 4 letter. This letter has become the focal point this week in claims that the palace was encouraging Kerr to dismiss Whitlam. It has inspired new conspiracy claims for those wanting to implicate the palace in the dismissal. Not satisfied with clear denials from Kerr and Charteris about the Queen not being informed, they now seek to satisfy their confirmation bias with new claims of coded language.

Charteris begins the letter empathising with the pressures Kerr is facing. He acknowledges that Kerr is “in the thick of the conflict” and writes on the assumption that Kerr is the prime agent and decision-maker. Charteris says his comments are merely “ingenuous”. He makes four substantive points in the letter.

First, Charteris confirms that the reserve powers of the crown to “dissolve parliament or to refuse to give a dissolution” do exist. This is despite the fact they have not been used for many years. He does not explicitly refer to the reserve power to dismiss a prime minister.

As a long-time student of the reserve powers, Kerr knew they existed. He had been schooled by former Labor leader HV Evatt, whose text The King and His Dominion Governors had surveyed the use of reserve powers in Commonwealth countries. It was unremarkable for Charteris, as the Queen’s private secretary, to tell Kerr these powers existed.

Second, Charteris says the “value” of the reserve powers arises from their capacity for influence. When “not used” by a governor-general, they can still affect the situation and “how people think and act”.

This refers to the classic use of the reserve powers and the fact they can be used as a lever to procure political settlements short of dismissal. This is the context in which Charteris discusses the powers.

Third, Charteris gives a clear warning to Kerr about the need for caution and constitutional responsibility. He says any “use” of the reserve powers carries “a heavy responsibility”. He tells Kerr they should “only” be used “at the very end when there is demonstrably no other course”. This is an unambiguous warning.

Charteris makes clear he understands Fraser’s tactic. He says Fraser wants Kerr to believe there is already a “constitutional” crisis because he wants Kerr to procure an election.

Charteris expresses confidence in the governor-general in “taking the line” that the crisis “has not yet crossed the threshold from the political into the constitutional arena”. This is another critical warning to Kerr against precipitous action.

Charteris assumes that Kerr is onside and congratulates Kerr for playing his role with “skill and wisdom”. The flattery is unmistakeable. But understand why he is being praised: it is because the governor-general is showing “impartiality” and avoiding any premature intervention.

Fourth, in case Kerr has missed the point, Charteris becomes even more emphatic. At the end of the letter, he assumes they are in agreement, saying of the reserve powers that “it is also clear that you will only use them in the last resort”.

This highlights what became the essential critique of Kerr’s action: that his ultimate recourse was to talk honestly to Whitlam and, alluding to his powers, ask Whitlam to advise a general election or, as governor-general, he might need to find another prime minister to provide that advice. In that situation, Whitlam could go to an election as prime minister or move against Kerr if he wished.

Whitlam’s final position of seeking a half-Senate election would not have been granted by any governor-general because supply would have expired before the election was held.

A series of misunderstandings have marked this week’s coverage of the letters.

The first is that Kerr acted improperly in his lengthy correspondence with the palace. Yet the governor-general, as the representative of the crown in Australia, has an obligation to report to the head of state. Every governor-general keeps the monarch informed of political events in Australia. They write regularly to the palace. That is part of the job.

Kerr’s letters were unnecessarily long and frequent, with the goal of cultivating the palace to ensure it was aware of his options. He is constantly seeking reassurance. It is thought the letters are a form of therapy for a man under pressure. But any notion that Kerr should not have been informing the palace of the most significant political crisis in Australia’s history is nonsense.

Heseltine said this week: “Certainly the governor-general acknowledged the responsibility of keeping her (the Queen) informed, which he did very conscientiously as the political scene changed in Canberra … he was talking to people and an institution which had been involved in political and constitutional matters for literally hundreds of years.”

The palace officials believed, in Heseltine’s words, that if Kerr had “been able to hold off for a couple of days more, the result might have been very different”. He said one possibility was that the Senate could have “given way” and passed the budget. Labor has always cherished this notion.

Interviewed on Friday, Paul Keating, who was the last appointed minister in the Whitlam government, told Inquirer that on November 11, 1975, when at Sydney Airport, he ran into senior opposition frontbencher NSW senator Bob Cotton. “We were together on the plane,” Keating recalled. “He said to me, ‘Paul, my bloke (Fraser) is mad, this thing is not going to last. This is not the way things should be done.’ ”

Historian Jenny Hocking deserves credit for launching legal action that enabled these letters to finally be released. They were always public records, not private records, and should have been categorised as such and released years ago.

But Hocking’s claim that the letters would reveal the palace gave Kerr “an unqualified royal green light” to dismiss Whitlam and that the Queen and her advisers were involved “in deep intrigue” with Kerr has not been proven. In fact, the letters show no “clear advance knowledge” or approval of Kerr’s dismissal, as Hocking claimed.

Hocking asserted that in September 1975, while in Papua New Guinea, Kerr flagged to Prince Charles that he was considering dismissing Whitlam and his fear of being recalled by Whitlam. Charles reported this conversation to Charteris.

A subsequent letter from Charteris purportedly “raised no objection to the prospect of the dismissal” and that the Queen would delay “for as long as possible” any attempt to remove Kerr from the vice-regal post. This established “a secret arrangement between the palace and the governor-general”, Hocking argued.

The Charteris letter dated October 2 is now released. In fact, it shows the opposite.

First, there is no mention of dismissing Whitlam. Second, in relation to the Queen recalling the governor-general on Whitlam’s advice, Charteris makes clear that the Queen “as a constitutional sovereign would have no option but to follow the advice of her prime minister”.

The conspiracy does not stack up. Charteris is somewhat indiscreet in this letter. He tells Kerr that the Queen, if given this advice by Whitlam, “would take most unkindly to it”.

That is hardly a surprise. Imagine the uproar if Whitlam had sought to sack Kerr during the crisis. The point, however, is that the Queen would follow such advice. Kerr knew this anyway and this is why he dismissed Whitlam by ambush.

Much of this entire debate begs the question: why would the Queen and her advisers have any interest in seeing Whitlam dismissed as prime minister with the inevitable controversy that this would generate? The unjustified focus on the Queen exempts the domestic players from their own culpability.

It was Fraser who ruthlessly forced the crisis by blocking the budget. It was agreed on both sides of politics that if Fraser had waited until the general election was due, he would have prevailed without any constitutional drama.

The fact Fraser won the 1975 and 1977 elections with large majorities was not a vindication of Kerr’s action but, rather, evidence of the deep unpopularity of the Whitlam government.

It was Whitlam’s ineptitude and misjudgment during the crisis that alienated Kerr, and his failure to have a contingency plan for a possible dismissal meant that Labor was clueless on the afternoon of November 11. Kerr was lucky because his dismissal of Whitlam might have unravelled if Labor had been alert enough to delay passage of supply in the Senate — one of the conditions under which Fraser became caretaker prime minister.

But, above all, it was Kerr’s deliberate strategy of acting by stealth and deceiving his prime minister because he believed a frank discussion with Whitlam would lead to his own recall that was ultimately responsible for the dismissal, with all its adverse consequences.

Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston are co-authors of the award-winning The Dismissal: In the Queen’s Name (Penguin).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout