The Palace letters: How the Dismissal played out in John Kerr’s words

John Kerr raised the prospect of dismissal almost two months before November 11, but was told to use powers as a last option.

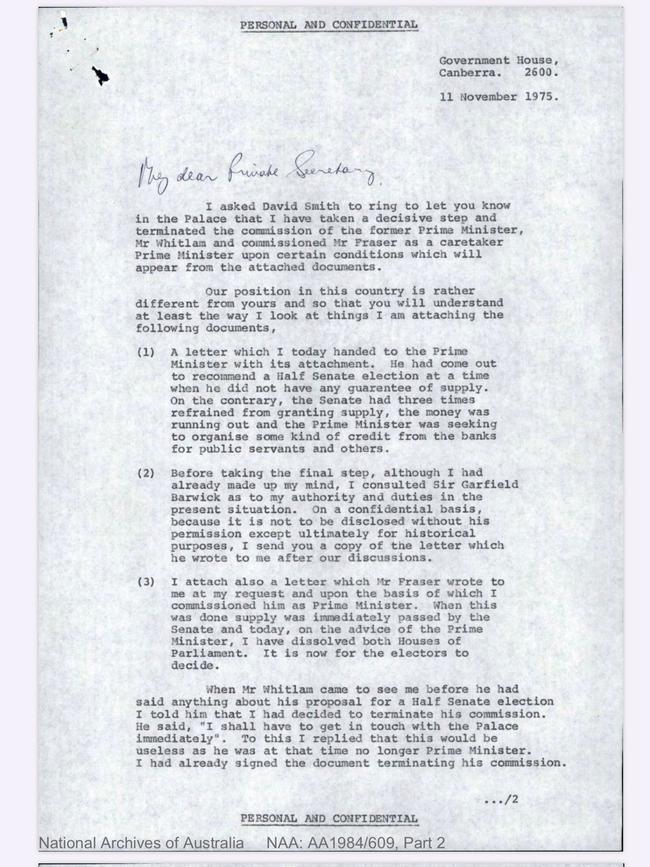

After Sir John Kerr dismissed Gough Whitlam in the afternoon of November 11, 1975, he retired to his study at Government House to pen a letter to the Queen’s private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, at Buckingham Palace.

“I have taken a decisive step and terminated the commission of the former prime minister, Mr Whitlam, and commissioned Mr Fraser as caretaker prime minister upon certain conditions which will appear from the attached documents,” he wrote.

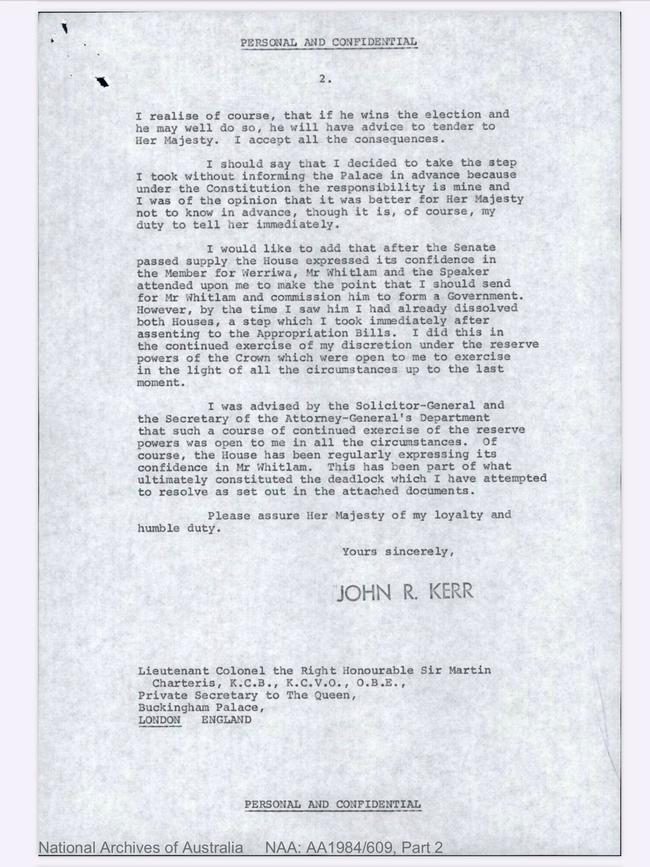

“I decided to take the step I took without informing the palace in advance because under the Constitution the responsibility is mine and I was of the opinion that it was better for Her Majesty not to know in advance, though it is, of course, my duty to tell her immediately.”

David Smith, the official secretary to the governor-general, had already phoned the palace with the sensational news. William Heseltine, the Queen’s assistant private secretary, had taken the call. He spoke to Charteris and they both informed the Queen later that morning.

Kerr had kept the palace informed about the constitutional crisis that had begun when the opposition, led by Malcolm Fraser, blocked supply in the Senate on October 16. The reason was the loans affair — an attempt to raise $US4bn from unconventional sources to fund national development projects — and the sacking of RFX Connor, the minister for minerals and energy, for misleading parliament.

Now, the governor-general had to set out what he had done to break the deadlock, and why he did it. The two-page vice-regal dispatch is clear, precise and to the point. The heavy justification for his unprecedented action — the dismissal of a prime minister without warning — would come in later letters.

“He (Whitlam) had come out to recommend a half Senate election at a time when he did not have any guarantee of supply,” Kerr explained. “On the contrary, the Senate had three times refrained from granting supply, the money was running out and the prime minister was seeking to organise some kind of credit from the banks for public servants and others.”

He had consulted the chief justice, Sir Garfield Barwick, who advised by letter the day before that if Whitlam “is unable to secure supply” he had to “resign or to advise an election”. Barwick was insurance. “I had already made up my mind,” Kerr wrote to Charteris.

Kerr had commissioned Fraser as a caretaker prime minister with conditions, including passing supply and advising an election. This had been fulfilled. “It is now for the electors to decide,” Kerr reassured the palace.

Informed, not involved

Meanwhile, Whitlam had rung Charteris at 4.15am London time. The first Charteris had heard of the Dismissal was from the deposed prime minister. “He spoke calmly and did not ask me to make any approach to the Queen, or indeed to do anything other than the suggestion that I should speak to you to find out what was going on,” Charteris wrote to Kerr on November 17.

Charteris was relieved that the Queen did not know about the Dismissal in advance. “I believe that in NOT informing the Queen what you intended to do before doing it, you acted not only with perfect constitutional propriety but also with admirable consideration for Her Majesty’s position.”

Not involving the Queen in the crisis was a priority for the palace. Charteris emphasised this in a letter on November 5. “It is good that people should know that the Queen is being informed but, of course, this does not mean that she has any wish to intervene, even if she had the constitutional power to do so,” Charteris wrote. “The crisis, as you say, has to be worked out in Australia.”

So Kerr had not given the palace advance notice of his plan to dismiss Whitlam nor did the palace approve it. But Charteris did offer Kerr reassurance in the November 17 letter that his actions could not “easily be challenged from a constitutional point of view” and he had not found anyone “who has been able to tell me what you ought to have done instead to resolve the crisis”.

Constitutional powers

There is a pattern of dialogue in Kerr’s vice-regal letters. Kerr would send dispatches with assessments of the political situation, provide analysis of his talks with both Whitlam and Fraser, and canvass the constitutional issues and possible resolutions to the crisis. They were loaded with attachments: media clippings, speeches, statements. And he frequently asked questions.

Charteris, invited to comment, obliged. On November 4, Charteris wrote to Kerr and referred to the reserve powers being used to resolve the crisis. Some doubted they existed. Not Charteris. “I think those powers do exist,” he told Kerr. But Charteris gave Kerr a warning about using these powers to dissolve parliament.

“To use them is a heavy responsibility and it is only at the very end when there is demonstrably no other course that they should be used,” he said. Charteris agreed with Kerr that the crisis — a week out from dismissal — was a “political” one and not yet “constitutional”. He reassured Kerr, flattered him, that he was approaching it with “skill and wisdom” and also “impartiality”.

But at the end of his November 4 letter, Charteris reiterated his caution to Kerr about the reserve powers. “The fact that you have powers is recognised, but it is also clear that you will only use them in the last resort and then only for constitutional and not for political reasons.”

This testifies to later testimony by Charteris and Heseltine that Kerr had acted prematurely and should have delayed acting so drastically — dismissal — until there was no other option available to resolve the crisis. This was the advice Charteris gave to Kerr less than a week before he terminated Whitlam’s prime ministerial commission.

Throughout the crisis and after, Kerr sought reassurance and support from old friends such as High Court judge Anthony Mason, former prime minister Sir Robert Menzies, Barwick and, of course, Charteris.

Kerr raised the possibility in September — a month before supply was blocked — that Whitlam might seek to have him assent to the money bills if they were passed by the house but rejected by the Senate. This prompted Charteris to suggest, if this happened, to ask Whitlam questions about the legality of doing so. Again, Charteris cautioned Kerr in an October 2 letter to “keep your options open and not to decide now what you will do in any given circumstances”.

A month earlier in Port Moresby, Kerr had raised with Prince Charles his perpetual fear of being recalled by Whitlam. This Kerr-Charles conversation was relayed to Charteris, who addressed it in a letter to Kerr on October 2. “If such an approach was made you may be sure that the Queen would take most unkindly to it,” he wrote. He flattered Kerr.

Charteris then delivered the news Kerr says he intuitively understood: the Queen would follow Whitlam’s advice. “It is right that I should make the point that at the end of the road the Queen, as a constitutional sovereign, would have no option but to follow the advice of her prime minister.

The upshot was that if Whitlam suspected Kerr was planning to dismiss him, and asked the Queen to remove him from office, she would have done so. This is hardly the response of a Queen who was party to Kerr’s plan to dismiss Whitlam by ambush.

Kerr cautioned

Kerr was obsessed about the reserve powers, including dismissal of a prime minister, long before he was sworn in as governor-general on July 11, 1974. He ruminated on their use in his extensive private notes and private conversations, and even raised it with Charteris before the constitutional crisis.

On September 20, thinking ahead to deadlock over supply, Kerr raised with Charteris that if public servants were not being paid, “it is said that only an election can resolve the point and if Mr Whitlam will not advise one I may have to find someone who will”. Kerr added: “My mind is at the moment open on this.”

So Kerr was raising the prospect of dismissal almost two months before November 11 and before supply was even blocked. This was unwise. But Charteris could hardly ignore this. In subsequent letters, he cautioned Kerr about using the reserve powers and stressed that they must only be a last resort. Moreover, Charteris urged Kerr to keep his options open right through to November. Kerr says he was. “I am however thinking hard,” he confided.

After the Dismissal, on November 20 Kerr wrote a lengthy six-page letter emphasising that he had tried to “arrange some kind of compromise” between the two headstrong leaders: Whitlam and Fraser. “The two leaders were both stubborn and proud men,” he wrote. The result was “a collision course” that would cause “enormous chaos and even political disaster”. Kerr says Whitlam effectively invited dismissal but claimed, again and again, that this was the only way to secure an election. But he judged Whitlam did not think dismissal was a realistic option. Why? Because Whitlam thought Kerr was “not strong enough to do it”. Fraser urged Kerr to exercise the reserve power of dismissal and threatened to criticise him if he did not.

In the November 20 letter, Kerr also felt compelled to address why he did not warn Whitlam of the Dismissal.

“I was in a position where, in my opinion, I simply could not risk the outcome for the sake of the monarchy,” he wrote to Charteris. Kerr argued that Whitlam would have sought to have him removed and this would have embroiled the Queen in the crisis.

In the weeks after the Dismissal, stung by the criticism over it, Kerr contemplated retiring from the vice-regal post. He raised it with Charteris, who advised him not to make a statement about resigning during the campaign or making an address to the nation, which Kerr had contemplated. To resign, Charteris reasoned on November 25, “could only be interpreted as a belief on your part that you had acted incorrectly”.

Kerr always wanted his letters to be made public one day. He thought they would support the account he offered in his memoir, Matters for Judgment (1978), and be of use to future historians given they contained a real-time record of the most controversial political event in Australian history.

“I would not expect to be hailed as a great literary and political letter-writer and showered with praise on that score,” he wrote in an unpublished book, The Triumph of the Constitution, “but as a participant in a great constitutional controversy I would have to be judged in a real sense partly on the basis of a real record.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout