Palace letters: John Kerr did not inform Palace ahead of Gough Whitlam dismissal

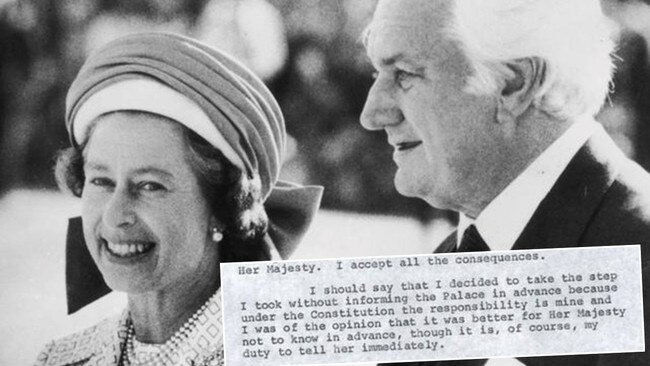

In an extraordinary intervention Buckingham Palace said the Queen played no role in Gough Whitlam’s dismissal.

Buckingham Palace has declared the Queen played no role in the dismissal of the Whitlam government in 1975, rejecting widespread claims — including from the Labor Party — that she had advised governor-general John Kerr on how to dismiss Gough Whitlam.

The extraordinary intervention was triggered by the release of previously secret correspondence between Buckingham Palace and the governor-general, revealing extensive discussion between Sir John and the palace about options to resolve the 1975 crisis including dismissal of the prime minister.

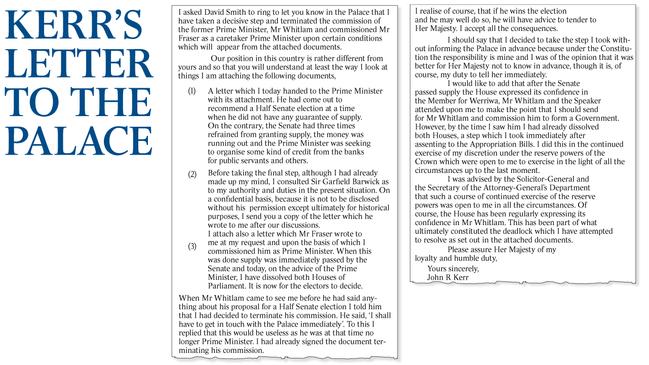

The letters confirm the official statement from the Palace. They show there was no advance notice of dismissal given to the Queen by the governor-general and no conspiracy involving the palace in the dismissal.

But the assurances in the letters that the Queen was not involved were rejected by the Labor Party on Tuesday. In a joint statement opposition legal affairs spokesman Mark Dreyfus and assistant spokesman Matt Thistlethwaite said: “What these letters reveal is that our unelected head of state, on the other side of the world, was advising the governor-general on how to remove our elected prime minister — and never once thought to tell the elected prime minister what was being planned.”

The letters show that six days before the dismissal the Queen’s private secretary, Martin Charteris, told Sir John: “It is good that The Queen is being informed but, of course, this does not mean that she has any wish to intervene, even if she had the constitutional power to do so. The crisis, as you say, has to be worked out in Australia.”

After the dismissal, letters from both sides, Sir John and the palace, made clear the Queen had no prior authorising role.

On November 17, Sir Martin wrote to the governor-general saying: “If I may say so with the greatest respect, I believe that in NOT informing the Queen what you intended to do before doing it, you acted not only with perfect constitutional propriety but also with admirable consideration for Her Majesty’s position.”

The force of the Queen’s statement on Tuesday night exposes the stakes involved — whether Australia will remain a constitutional monarchy. If the Queen was a party to the dismissal decision then her moral and political status as Queen of Australia would be compromised in the eyes of the Australian public.

A Buckingham Palace spokesman said the letters confirmed the Queen had no role in Whitlam’s dismissal and she respected the “independence” and “primacy” of Australia’s Constitution. “At Her Majesty’s Coronation on 2 June 1953 the Queen swore an oath to govern the Peoples of Australia ‘according to their respective laws and customs’,” the Palace spokesman said.

“The release of the letters by the National Archives of Australia confirms that neither Her Majesty nor the Royal Household had any part to play in Kerr’s decision to dismiss Whitlam.”

The letters show the palace was grateful to Sir John for ensuring the Queen was not involved in his dismissal decision. But they reveal a sustained effort by the governor-general before and after the budget was blocked to cultivate the palace, keep it informed of progress and outline the options he might face including dismissal.

The correspondence reveals that Sir John as early as September 20, three weeks before supply was blocked, told Sir Martin that if Whitlam refused to advise an election in any future deadlock then “I may have to find someone who will” — a reference to the dismissal option and making Malcolm Fraser prime minister.

Persuading Sir John to dismiss Whitlam was the heart of the Fraser strategy. In his November 20 letter to Sir Martin, Sir John revealed that in his last discussion with Fraser he was “warned” by the opposition leader. Fraser said “the last moment was arriving when the reserve powers of the Crown could be exercised” and if Sir John failed to act then Fraser would publicly criticise him. He told Sir John such inaction meant the reserve powers “would be destroyed forever”.

But Fraser was not the only leader to threaten Sir John . In the same letter the governor-general said Whitlam had warned him the only way an election could be obtained was if Sir John did “a Sir Philip Game” — that is, sacked him — but he would not be “strong enough to do it”. Sir John felt Whitlam’s statement “had an element of threat about it”.

Much of the controversy about the Queen’s role arises from the letter Sir Martin sent Sir John on November 4. Sir Martin says that while the reserve powers “or the prerogative of the Crown to dissolve parliament” had not been used for many years he believed that the reserve powers still existed. Sir Martin referred to dissolving parliament not dismissal of the prime minister.

This was not a surprise for Sir John. He had not the slightest doubt the reserve powers still existed. But Sir Martin then gave Sir John some guidance. He said: “But to use them (the reserve powers) is a heavy responsibility and it is only at the very end when there is demonstrably no other course that they should be used.”

In essence, Sir Martin was now advising caution on the governor-general in ¬emphatic terms. In order to emphasise this point he repeated it in the same letter saying the fact that Sir John had the powers was “recognised” but it “is also clear that you will only use them in the last resort and then only for constitutional and not for political reasons.”

Sir Martin was not encouraging Sir John to sack Whitlam. He was doing the opposite — urging him to see the reserve powers as a final resort. The assumption from the palace in this letter is that Sir John had the decision-making responsibility, not the palace. Sir Martin in this letter was encouraging Sir John to act responsibly.

The following day in his letter of November 5 to the governor-general, Sir Martin emphasised, yet again, the Queen had no wish to intervene in the decision-making. Any idea that the palace should have told Sir John not to use the reserve powers would have been a direct and huge intervention in the crisis and a manifest breach of the Queen’s responsibility to leave the decision to the Australian system.

In Sir John’s November 11 letter to Sir Martin he said: “I decided to take the step I took without informing the Palace in advance because under the Constitution the responsibility is mine and I was of the opinion that it was better for Her Majesty not to know in advance.”