Labor’s manufacturing dreams crash into the new world disorder

Anthony Albanese’s big bet on manufacturing already looks like a grand folly. Here's what the experts say.

Three decades ago, most people in the political and media class would have been able to answer those questions; voters would be aware of the competing policy suites to achieve those goals. It was the era of consensus, reform and upheaval.

Today the long view is not so clear, partly because our politics is obsessed with the short-term, and the prize is not as apparent as it is for, say, a developing nation trying to take its people out of poverty.

The post-pandemic world is one of rapid transition, amid a polycrisis of fragmenting global trade, rising protectionism, indebtedness, high inflation, food shortages and entrenched military conflicts.

We face what economist Pradeep Philip has called the “arc of disruption”, as we confront the pressing structural shocks of technologies such as artificial intelligence and the challenge of decarbonisation that will change the production system in every market, industry and economy.

“Today we find ourselves not at an inflection point but at a point of bifurcation that seems to be taking place in real time before us,” the Deloitte Access Economics lead partner told the Economic and Social Outlook conference hosted by the Melbourne Institute and this newspaper in November last year.

That’s the backdrop for Anthony Albanese’s Future Made in Australia push, which he promoted at our conference lunch. In the days leading up to that gathering, with its theme of “Bold Ideas for a Defining Decade”, the Prime Minister visited the Bundaberg brewery, Darrell Lea’s factory in southwestern Sydney and the SunDrive solar cell facility at Kurnell in Sydney’s Sutherland Shire.

The contours of “Albonomics” were sketchy, to say the least, during the 2022 campaign but they became clearer six months ago: self-sufficiency at home, or “resilience” as he put it, while trying to set the nation up as a “renewable energy superpower”.

Because the market alone could not deliver Labor’s green new deal, Canberra had to provide the guiding hand and taxpayers would bear the risk. As Jim Chalmers laid out at the event, there would be a honey pot of subsidies for investors who met rigid tests and a group of chosen industries that were seemingly born ready for this adventurism.

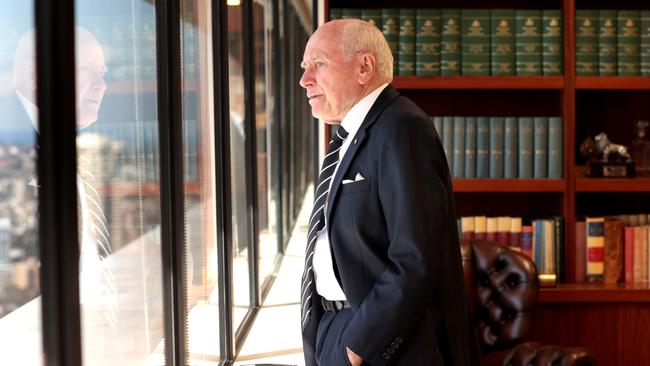

Labor is going full throttle on industry policy, in defiance of the advice of the old policy establishment, the wreckage of our lost years of protection and its own history. Albanese does not need JW Howard, of all people, to remind him of Bob Hawke’s legacy in dismantling the tariff wall. As a side note, a decade ago the Productivity Commission found the transitional assistance to moochers Ford, Holden and Toyota, with their eyes on the exit, was $30bn between 1997 and 2012. John Winston was prime minister from 1996 to 2007.

Deloitte’s Philip may be a systems and strategy guy with a PhD but he’s grounded and politically attuned. He worked in Kevin Rudd’s PMO and was secretary of Victoria’s department of health and human services. He tells Inquirer we’re in the world of “creative destruction” identified first by Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter, “where value destruction will take place in order for value creation to establish a new economic structure”.

And it’s coming at us fast, while we’re stuck in what Philip laments is the current “vacuous debate on industry policy, that is shrill at the edges”. But it’s a conversation we need to have and the retreat from globalisation by Joe Biden – in fact all our allies and major trading partners – means the game has been transformed.

Philip argues it’s a fallacy to think that not acting or responding is costless. “Change is the inevitability,” he says. “Being strategic about this, not simplistically doctrinaire, has always been the art and craft of good policymaking – something we need to nurture and rebuild more fully.”

The International Monetary Fund is now tracking the return of industrial policy. Last year, there were more than 2500 new interventions, 1800 of which it said were “trade distorting”. Looking at the prime movers, the US, China and EU, the team said, on average, there was almost a 75 per cent probability a subsidy for a given product by one major economy was met with a subsidy for the same product by another within one year. “The pursuit of (industrial policy) by some countries has also raised alarm in others over loss of economic and national security and a vortex of tit-for-tat retaliation, a challenge the multilateral rules-based trading system seems ill equipped to deal with,” IMF researchers reported in January.

In its recent Fiscal Monitor, the IMF declared: “History shows that industrial policy is prone to policy mistakes. Even when projects transform industries, they often entail high fiscal costs and negative cross border spillovers”.

This is one way, albeit a dispiriting one, of understanding Albanese’s framing of the evolving state of play as “the new competition”. The official family of economic advice, slandered “flat-earthers” (or emeritus wise uncles of the Productivity Commission) and veteran editors are going to have to win the arguments all over again.

Philip says it has been decades since Australia had a proper debate or even a view to an integrated strategy for economic development, as opposed to growth. That’s a distinction that matters at points of structural change. “Policies that are protectionist in a world of globalisation might not be so in a world of fragmentation,” he says.

“Our own economic allies have shifted the goalposts. But we should still advocate for globalisation as that suits small open economies, but we need to act in ways that preserve, let alone build, our prosperity.” In any case, Philip declares “strategy is not about purity”. “There are the usual significant risks in the Prime Minister’s plan,” he says.

“But there are also huge costs in not acting from a strategic perspective. So return on investment on public spending is critical and we are yet again at the nub of public administration – the problem of implementation.”

Productivity Commission chairwoman Danielle Wood made a splash a fortnight ago when she asserted the independent body’s corporate line on the day Albanese announced he would be legislating a Future Made in Australia Act as a policy umbrella for existing and new initiatives. But there were caveats.

For one, she told Inquirer straight off the bat, “it’s unclear exactly how big any new subsidies might be and what they will target”. Plus it was worth remembering “that many of the costs of industry support are still there”. Wood then outlined the ongoing heavy costs to taxpayers of support, the political incentives to keep the money flowing to companies unable to stand on their own feet, and the diversion of scarce workers and investment to less productive uses.

This is the funding black hole of the past we thought Australia had escaped, yet governments are still pouring in almost $14bn a year in industry assistance. Not all of this, of course, is wasteful; given the global mania for subsidies, second-best and costly energy transition, geopolitics and local political considerations, it is now also largely unavoidable.

We need to support young, innovative businesses, as distinct from what economist Saul Eslake calls the failed approach of “small business fetishism”. The full company tax rate is 30 per cent, while “base rate entities” (with a turnover below $50m) pay 25 per cent. Eslake argues if preferential tax treatment and other forms of assistance are to be provided to any businesses, it should be to new businesses rather than small ones.

Even the IMF says using industrial policy to promote innovation can deliver returns, but only if the social benefits (or “externalities” in econospeak) are well measured; knowledge spillovers from subsidised sectors are high; administrative capacity is strong; and policies do not discriminate against foreign firms.

The IMF is pushing for more public funding of fundamental research with wide applications; such policies easily pay for themselves in the long term. As well, it suggests research and development grants for innovative start-ups, and tax incentives to encourage applied innovation across firms.

“But design matters,” it warns. “Grants are most useful if targeted to earlier stages of the innovation life cycle, for example, while tax incentives must be easy to access if they are to benefit more than just the large established firms.”

This should not be seen as a green light from the monetary druids in DC, but rather a sense of the very high bar required to avoid the miseries of our past. To make sure that new support makes sense, the PC’s Wood is encouraging the government “to be very clear in specifying their policy objectives”.

“Understanding whether we are trying to reduce supply chain risks, speed up the green transition or create jobs is needed to help evaluate whether the policies stack up,” she says.

“We would also really encourage governments to make sure they have an exit strategy. If the purpose of the policies is to support emerging industries, making sure that we have a policy to at least review if not formally wind back support is important to minimise the costs.”

Will they listen? An election is due in just over 12 months. As the ageing vigilantes fear, the horse may have bolted. We’ll find out in next month’s budget how much will be going out the door and how strict the governance will be.

But it already looks like a grand folly, with the rhetoric, the vibe and hot blood running ahead of evidence-based policy rigour.

A newly arrived foreign diplomat recently asked a federal MP to describe Australia’s vision for its future. What’s the nation’s mission statement? What were the sources of Australia’s future prosperity? The politician was stumped.