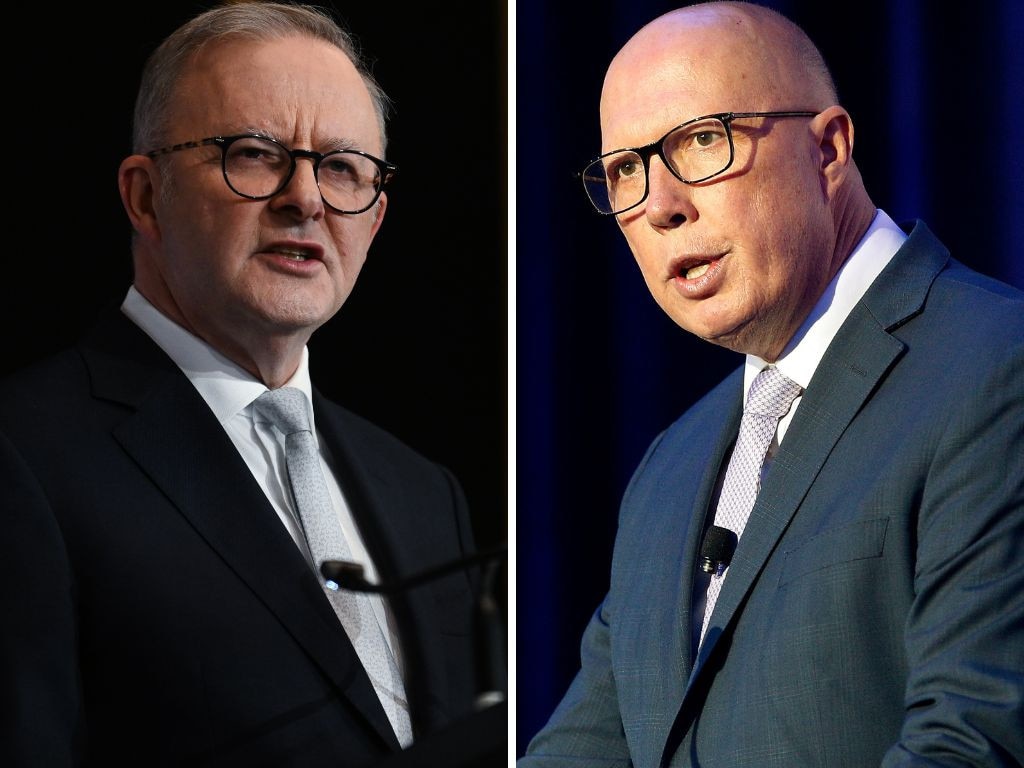

Future Made in Australia: Productivity Commission’s Danielle Wood reveals hidden cost of Anthony Albanese’s future

Jim Chalmers’ hand-picked Productivity Commission chair warns the Future Made in Australia plan would divert investment from more productive parts of the economy.

Jim Chalmers’ hand-picked chair of the Productivity Commission has warned Labor’s Future Made in Australia plan would divert investment from more productive parts of the economy and lead to higher-than-necessary costs for taxpayers.

Danielle Wood – the former Grattan Institute chief executive who the Treasurer tasked with shifting the commission’s focus towards the energy transition – said Anthony Albanese’s proposed subsidies for the low-emissions manufacturing sector would “take jobs and capital investments from elsewhere in the economy where they could generate higher value”.

“In a period of tight labour markets, and many areas of growing future demand for labour, this compounds the costs of industry support,” Ms Wood said, in her first major intervention on government policy since being appointed last year.

With the Prime Minister on Thursday drawing the battlelines for the next election by unveiling plans to create Australia’s response to the US Inflation Reduction Act, economists said his proposal would be inflationary while business groups warned a government-led approach risked wasting money.

The Prime Minister’s vow to legislate a Future Made in Australia Act, to co-ordinate a whole-of-government package of new and existing projects to drive investment in manufacturing and clean-energy technologies, came a day after the International Monetary Fund said the rapid rise in industry support was “not a magic bullet”.

Australian Industry Group chief executive Innes Willox, who represents manufacturing businesses, said industry policy was “fraught with pitfalls”.

“Too often, government policies distort activity, create unintended consequences and are slow to adapt as circumstances change and flaws are exposed,” Mr Willox said. “Yet we are today invited to make a leap of faith that more government guidance and support is the answer to our ills. Industry will naturally view the promise of more government intervention with suspicion, if not alarm.”

Minerals Council of Australia chief executive Tania Constable said “we should not forget that it is companies that create competitive industries, not government”

Business Council of Australia chief executive Bran Black said: “Any government intervention needs to be carefully calibrated and measured so taxpayer funding isn’t wasted, inflation isn’t fuelled further, and private funding isn’t crowded out.”

Independent economist Saul Eslake said manufacturing was a “low-productivity form of economic activity” in Australia, with the sector’s gross value per hour worked about 11 per cent below the all-industry average.

Mr Eslake calculated that last financial year, labour productivity for manufacturing was $79 per hour, compared with the all-industry average of $89 per hour. In capital-intensive mining, labour productivity was $759, while financial services ($186), utilities ($182) and information, media and telcos ($166) were also at multiples of the economy-wide average.

Mr Eslake, who runs Corinna Economic Advisory, said “manufacturing fetishism” and an “obsession with sovereignty” had infected both major political parties, with politicians ultimately “failing in basic arithmetic”.

He said building up manufacturing as a share of the economy, would mean other parts of the economy would inevitably be squeezed. On the face of it, he said, policies directing more capital and labour to manufacturing via subsidies and tax incentives would detract from labour productivity, which had been stagnant for a decade – “unless those resources are shifted from sectors with even lower labour productivity than manufacturing, such as retail trade, accommodation and food services, or construction”.

“It’s not immediately obvious that those sectors are where the resources to be shifted into manufacturing, as a result of what the government is proposing, are going to come from,” Mr Eslake said.

Former ACCC chairman Rod Sims said there was a huge economic opportunity in green industries, and he was waiting for a “tighter framework” over how the tens of billions in taxpayer dollars and subsidies would be put to use.

Mr Sims said he was encouraged by Mr Albanese’s reference to promoting projects where Australia had a comparative advantage over other countries, such as in renewable energy and critical minerals. But creating or propping up uncompetitive industries would “lower our standard of living, because you have people working in sectors that aren’t as productive”.

“We are clearly running into a future where there are shortages of labour, and there are real consequences if we don’t get that right.”

Ms Wood, who backed Bill Shorten’s 2019 tax agenda on superannuation, negative gearing and franking credits, acknowledged it was unclear “how big any new subsidies might be and what they will target”.

But she said it was important for the government to have an “exit strategy” from support programs and to be mindful of the sunk costs, year after year, for industries that could not “stand on their own two feet”.

Ms Wood said that while the government was right that there were “new considerations at play including shifting geopolitical sands and the need to transition to the green economy”, it was worth remembering that many costs of industry support were still there.

According to the Productivity Commission, Australian governments spent $13.8bn in 2021-22 on industry assistance, perhaps more if a myriad of carbon-abatement measures that support private businesses were included.

“For industries that are not able to ‘stand on their own two feet’ in competing globally, more money will be needed for every year we choose to ‘rent’ the industry,” Ms Wood said. “Second, we will see a whole class of businesses whose livelihoods depend on ongoing support, which will have an incentive to spend a lot of time and resources ensuring that the tap is not turned off. To make sure that new supports make sense, we would encourage the government to be very clear in specifying their policy objectives.

“Understanding whether we are trying to reduce supply-chain risks, speed up the green transition or create jobs is needed to help evaluate whether the policies stack up.”

Mr Eslake said that in a globalised economy to be successful in manufacturing at the moment you needed scale because the activity had high fixed costs.

“Australia lacks a large domestic market or proximity to its customers, so we can’t achieve that scale to succeed,” he said.

He added that when industries operated behind the tariff wall from Federation to the 1980s, growth in living standards fell behind other countries.

Mr Eslake said one of the reasons for Australia’s poor overall labour-productivity performance over the past decade was that an increasing share of hours was being worked in the intrinsically labour-intensive, and hence inherently low-labour-productivity, “care economy”, as the Treasurer calls health, aged care and disability services.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout