Indigenous voice legacy: hope, division, paralysis

The voice represents a tragic saga for Aboriginal Australians. The wounds are still fresh – and there’s little sign of leadership to identify a way forward.

But the wounds are still fresh. Blame is being attributed in different directions. There is little sign of leadership to identify a way forward. Perhaps the hardest thing is to recognise the limits of the referendum’s defeat – it was not a repudiation of Indigenous peoples; it does not extinguish goodwill; and it cannot be seen as undermining the capacity of Australians to live together.

Much of the country seems confused or indifferent a year later. Bipartisanship remains a lost cause. The major disappointment has been the extraordinary absence of an initiative from the Albanese government, working with the Coalition and Indigenous leaders, to build a new political framework.

There is no excuse for the Albanese government. Professional politicians are expected to regroup after a setback. For Labor and the Yes case the reality is the need for a rethink and new direction. The Yes case was filled with ambition but it overreached, the upshot being a double defeat – no constitutional recognition and no voice. It was a misjudgment on a mammoth scale.

There were, in retrospect, alternative options. For instance, if the legislative route had been taken for the voice, it would have been authorised by the parliament and would be operating by now. And if the symbolic route had been taken for constitutional recognition, based on achievable Labor-Coalition bipartisanship, the referendum (without any voice) might have been carried by now.

The upshot could have been a transformed Indigenous landscape – but this was never an option given the Indigenous leaders insisted on their big gamble. They fiercely rejected symbolic constitutional recognition and rejected creating the voice by legislation even when they had the numbers in both houses to achieve that. Future historians will ponder on this conundrum.

Constitutional recognition and the voice were separate ideas. There was no iron logic saying they needed to be tied together. The mistake the Indigenous leaders made was their high ambition saying that constitutional recognition must come through the mechanism of the voice.

A new direction in Indigenous affairs is the inexorable logic from the referendum defeat. But where that new direction goes is undefined. Anthony Albanese’s retreat from implementing the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full has provoked hostility from many of the Yes campaign Indigenous leaders. The issue of the treaty is being left to the states. Federal Labor seems immobilised.

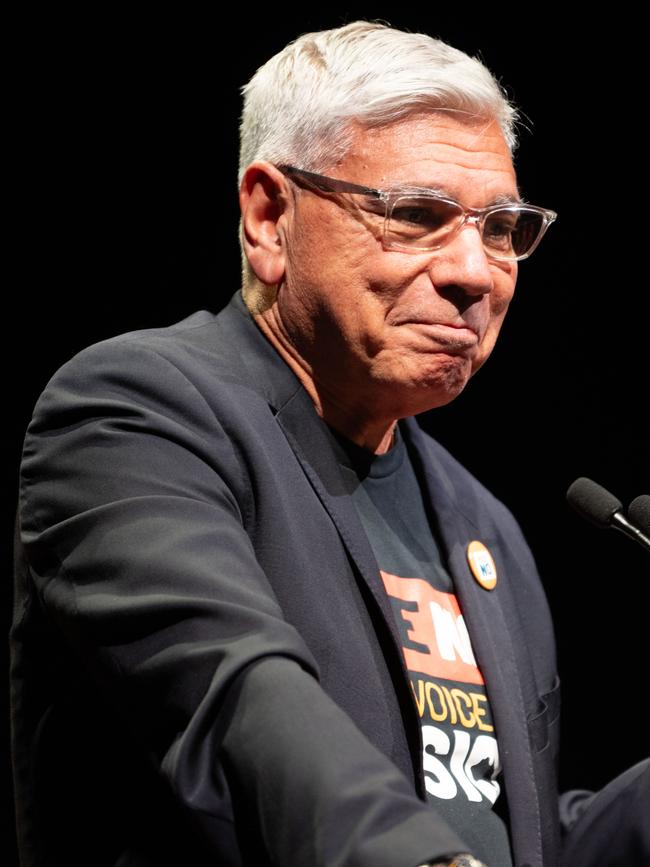

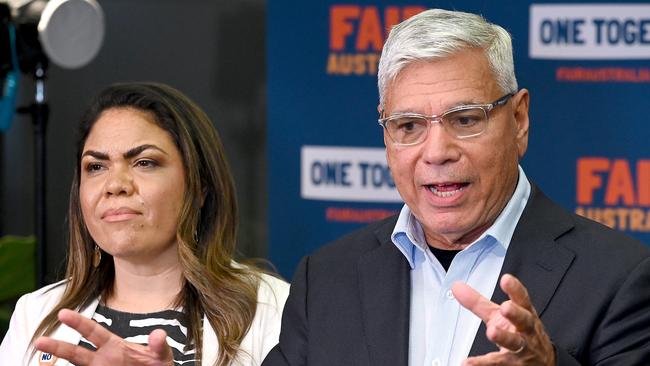

The leaders of the No campaign, senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Nyunggai Warren Mundine, see the referendum’s defeat as a pivotal opportunity for fresh policy, yet they are being thwarted by a paralysed power structure.

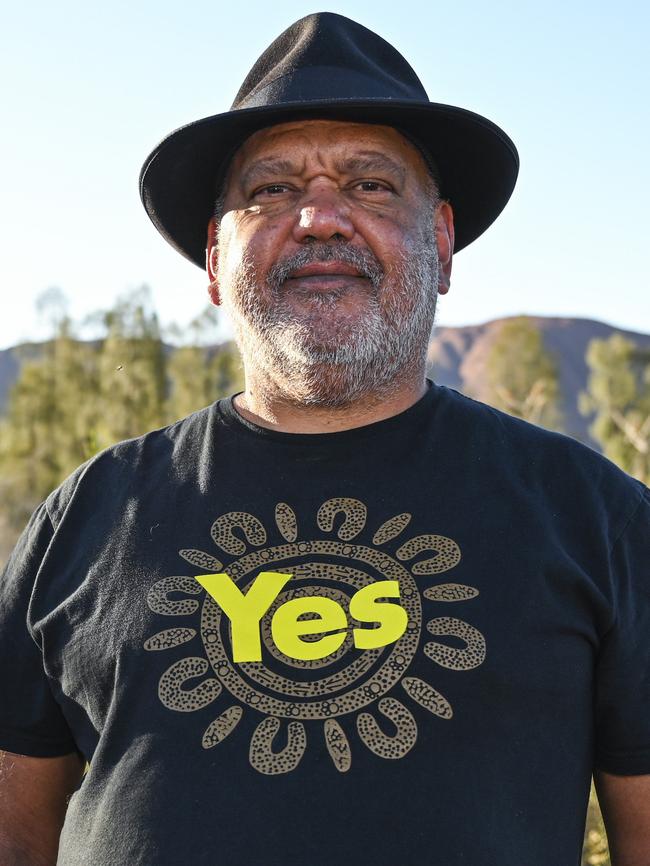

Amid the dismay of the Indigenous leadership at the 2023 defeat, the most powerful philosophical remarks about the future came from Noel Pearson, an architect and campaigner for the voice. Several months ago, he told the author: “In the wake of the referendum loss, we have to find a third way. I am disillusioned because I thought the voice was a third way. But I cannot help but return to the fact that belonging to Australia is the only way forward for us. After the referendum defeat there are three possible responses. One, just capitulate and admit defeat. Two, being bitter, disillusioned and alienated. And the third way – that we keep making the case we belong to Australia, we belong to this nation.

“Our advocacy has got to be about belonging. We are part of the nation. We have nowhere else to go. This is our country and we have to keep making the cause for unity and inclusion.”

Pearson’s message is not for separation, resentment or resignation. It is a call for hope, even when the direction is unclear. It reminds that the quest for reconciliation and “closing the gap” is a permanent process.

Nampijinpa Price told Inquirer, “The Albanese government and proponents of the Yes campaign are completely in denial even a year on from the referendum. There’s an ongoing failure to recognise the need to take action to address the needs of marginalised Indigenous Australians.

“There is no bipartisan approach from this government. It’s their way or the highway and their way is failure. They put a referendum telling us they wanted a voice but they’re not interested in hearing the voices of Indigenous Australians who want practical solutions.”

The message from Mundine is not to conflate rejection of the referendum with rejection of Indigenous Australians. Mundine told Inquirer: “Everywhere I went during the campaign – whether I spoke to Yes supporters or No supporters – there was massive goodwill towards Aboriginal people. People wanted things fixed, they wanted the ‘gap’ closed, they wanted practical improvements. I travelled the entire continent and this was the sentiment everywhere. The idea this vote was about racism and bad will towards Indigenous people is absolute nonsense.”

Asked why the referendum was defeated, Mundine said it offended the equality principle: “The reason becomes clear when you look at the successful 1967 referendum. The 1967 vote was about equality, about bringing Indigenous Australians into the wider Australian community. That’s what people wanted; in 1967 they saw this as a no-brainer.

“What happened in 2023 was different: a proposal to put race into the Constitution – and I know the Yes side denies this – but the public saw the proposal as not treating people on an equal basis.

“That was the response I got everywhere I went. It was particularly strong in migrant communities – they saw this as treating people differently by race and they wouldn’t accept it.”

In assessing the referendum’s defeat, two realities should be acknowledged.

First, Albanese as Prime Minister misjudged his responsibilities saying the voice referendum was an invitation by the Indigenous peoples to the Australian people. This was a disastrous formulation, despite suiting some Indigenous leaders who wanted to be front and centre in the campaign. It was Albanese’s job to insist on a process to negotiate the model with the best chance of success.

He didn’t do that. Yet with Labor’s record being one win out of 25 referendums since Federation it was essential. During the native title debate Paul Keating as prime minister confronted the Indigenous leaders, negotiated with them and wound back their demands. That’s how a prime minister should act when authorising a referendum question.

Second, the entire debate proceeded in ignorance of conservative and Coalition politics, a catastrophic failure. In retrospect, the voice was lost in October 2017 when it was rejected by the Turnbull cabinet.

Off the back of a recommendation from the independent Referendum Council the cabinet rejected the idea with Turnbull as prime minister, George Brandis as attorney-general and two future Liberal leaders at the cabinet table, Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton. The voice was friendless. The rejection was unanimous. Turnbull and Brandis were Liberal moderates. The author said at the time the cabinet had no sense of political ownership of the proposal.

Turnbull’s formal statement of rejection was explicit. It said Australian democracy was built on the idea of “citizens having equal civic rights” and a “representative assembly for which only Indigenous Australians could vote for or serve in is inconsistent with this fundamental principle”.

This was the argument Dutton used six years later in campaigning against the voice. Virtually nothing had changed in six years. The voice was found against in 2017 on grounds of fundamental principle – breaching the democratic equality along with the electoral view any voice referendum had no hope.

Yet much of the public and media debate in the following years refused to take this cabinet decision seriously, largely ignoring the in-principle basis for rejection, attacking the Coalition for shallow and populist politics and assuming that under pressure the Coalition under Dutton would buckle and change its mind. This was most unlikely. Labor and the Yes case ran on a proposal never likely to win bipartisan support. The shadow of 2017 hung over the 2023 referendum.

Fundamental to the voice legacy is the split in Indigenous leadership exemplified by the division between Nampijinpa Price, and the Yes Indigenous advocates. Nampijinpa Price did not just say No to the voice; she called for a revisionist agenda and a new accountability in Indigenous affairs. Her targets are both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous power structures. This will have long-term consequences.

Nampijinpa Price wants no voice, no treaty, an end to “neo-colonial racial stereotyping” and insists the central blunder in Aboriginal policy has been the elevation of “grievance before fact”. Drawing on her experience in the Northern Territory, Nampijinpa Price said policy had been based on a false priority: race, not need.

Her message, like that of Mundine, is for practical improvements for Aboriginal people in education, housing, jobs and economic enterprise. Nampijinpa Price sees the historical template of Aboriginal people as victims as counter-productive, ruining their agency and a misleading “romanticism” of Aboriginal culture. She is a fusion of conservative and radical. Her standing in Coalition ranks after the referendum means she will exert a huge influence on Indigenous policy within the Liberal and National parties.

Nampijinpa Price’s rejection of campaigns around recognition and treaty points to ongoing fundamental division but, even in their views on how best to “close the gap” Nampijinpa Price and Mundine offer frontal challenges to the progressive orthodoxy and existing power structure.

Nampijinpa Price has been thwarted by the Senate majority in her efforts to establish an inquiry into Aboriginal land councils that have immense control over land and funds, saying such Indigenous bodies are “not functioning the way they could be” and were not promoting economic independence for Indigenous Australians.

Two months ago Mundine published an analysis, Where to Now?, for the Centre for Independent Studies, its central theme being: “Australians do not want divisive and ideology-driven solutions or race-based policies. Australians want real improvements in Indigenous lives and policies directed towards need that deliver outcomes.”

In principle this should gather wide support; in practice the obstacles will be significant. Mundine identified four priorities – economic participation, education, safe communities and accountability. But he wanted a decisive break from existing approaches.

His first big target was “that traditional lands are collectively owned and controlled”. Individual property ownership is not permitted. It is a model of “government-sponsored socialism” that denies “the key building block for a real economy: private land ownership”. The upshot is “communities have almost a complete absence of commerce”. A vicious cycle is set up – low school attendance, low education outcomes, weak business activity, social dysfunction and crime.

A functioning market economy, the proven method of success around the world, is actively discouraged. “Business ownership – the most important foundation of an economy – is almost non-existent,” Mundine said. Yet a system with nearly two-thirds of people in remote communities not working is buttressed by stakeholder interests.

Mundine said: “It is hard to understand why the federal and NT governments have to pay for housing on Aboriginal lands when there are billions in Aboriginal land trusts and other bodies, including from royalty payments and native title payments.”

The real tragedy of the voice proposal is that it was conceived as a measure for a conservative government. The originating discussions were held in 2014 at the Australian Catholic University campus in North Sydney, three years before the Uluru statement, with a small group involving Cape York leader Pearson, his adviser Shireen Morris, Australian Catholic University vice-chancellor Greg Craven, Julian Leeser from the ACU, University of Sydney lawyer Anne Twomey and lawyer Damien Freeman, among others.

The group settled on the voice concept having decided the earlier idea of an anti-racial discrimination clause in the Constitution would be rejected by the Coalition and the conservative movement. Twomey subsequently told the Sydney Institute the voice proposal “was originally designed for a conservative government to put to a referendum” – with Tony Abbott being prime minister at the time and supporting constitutional recognition in principle.

For Pearson, winning conservative support was pivotal. He often called the project a “Nixon goes to China” moment – that is, only conservatives added to centre-left support could deliver the necessary majorities. Three years later in a major political feat spearheaded by Indigenous leaders Megan Davis, Pat Anderson and Pearson the Uluru statement endorsed the voice and a Makarrata to oversee treaty-making. Pearson called the idea “a constitutional bridge to create an ongoing dialogue between the First Peoples and Australian governments and parliaments” to close the gap. In her book on the referendum Morris lamented that the voice came to be viewed as a “progressive” idea and that from the time of Albanese’s election night commitment in May 2022 it “was officially owned by the left”.

That’s true, but it was surely a political inevitability. Once Albanese proceeded without any early effort at a parliamentary or convention process to win broader support the referendum was set to become a Labor-Coalition divide with Indigenous spokespeople on both sides.

Veteran supporter of Indigenous rights Father Frank Brennan said in his post-referendum analysis: “The government’s process was never designed at getting the Liberal Party led by Peter Dutton on board. As a well-intentioned bystander, I had watched the train wreck coming. If you want to amend the Australian Constitution you need a process from which no one is excluded. You’ll never get this unless you’ve got the leadership of all major political parties on board.

“I thought it necessary to do all I could to improve the process and the wording. I failed, as did many others. Peter Dutton, like his predecessors Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison when each of them was prime minister, never came aboard. Liberal leaders had ruled out the Pearson option at every turn. In the meantime the Uluru processes ruled out everything except the Pearson option.”

Albanese’s strategy worked only if Australia had changed fundamentally as a country – and many Labor people felt, in the hubris of 2022 and 2023, having won the election, seen the teals steal the prized Liberal heartland and watched the triumph of same-sex marriage, that Australia had gone progressive and the voice was next on the agenda. They misread their country. Being realistic, however, it is difficult to see how even in a constitutional convention the Coalition would have supported the voice.

Moreover, the concessions Albanese would need to have made would have been unacceptable to the Indigenous leaders. Hence, it was a doomed project. Therefore, the legislative route was always the best prospect for its advocates.

The further tragedy is that by putting a flawed referendum new divisions have been created. In The Australian (published on September 27) Geoff Chambers and Paige Taylor sampled opinion among Yes advocates and found resentment towards the Albanese government, frustration at the public’s ignorance of the disadvantage of Aboriginal people living in remote communities and the belief that lies and misinformation were basic to the voice’s defeat.

Constitutional law professor Davis said she was “living in a parallel universe whereby this thing I’d worked on for 12 years was captured by politicians and people of bad faith and there was nothing we could do”. Davis said: “Our people are still grieving. Australia is not what we thought it was. Slowly it’s dawning on people, especially the government, how detrimental misinformation is to public debate. The lies and nonsense about what the voice would do or could do was impossible to combat because lying in politics, especially in the 2023 referendum, was acceptable.”

Davis said there was no evidence “it was the wrong proposal or that it was the wrong time or that it would not work”.

This defies the entire foundation of the No case and majority public sentiment. In essence, the voice was a radical concept – it was a group rights political body, defined by racial ancestry, in tension with the notion of democratic equality, given a constitutional standing virtually in perpetuity, sitting next to the House of Representatives and Senate with a sweeping advisory brief to the parliament and executive government on nearly all aspects of public policy (since most policies affect some Indigenous people) and designed to exert a political and moral influence within the system of government. It is unsurprising the public voted it down decisively. It won’t be easy but the task ahead is to navigate a better direction.

The defeat of the October 14, 2023, referendum on the Indigenous voice – now at its first anniversary point – represents a tragic saga for Aboriginal Australians, highlights the need to learn the right lessons from the vote and work to repair the national social compact in relation to First Australians.