Indigenous voice to parliament special investigation: Yes campaign leaders felt ‘invisible’ as referendum became toxic

Australians backing the Indigenous voice to parliament felt ‘swept under the rug’ as Anthony Albanese’s referendum became an unmitigated disaster.

Indigenous Yes campaigners felt “invisible and swept under the table” as Anthony Albanese’s doomed constitutional voice referendum descended into a politically toxic and unmitigated disaster.

The Prime Minister’s gradual retreat from his 2022 election promise to implement the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full has left bruised Indigenous leaders struggling to find their voices after the heavy referendum defeat on October 14 last year.

Approaching the one-year referendum anniversary, key figures who led the Yes23 campaign and Uluru Dialogue are among dozens of Indigenous leaders who have broken their silence about what went wrong, the blame game and way forward.

In their first significant public dissections of the referendum result, Yes23 campaign director Dean Parkin and Uluru Dialogue co-convener Megan Davis opened up to The Weekend Australian about their heartbreak, political interference that undermined the Yes campaign and their hopes for the future.

Parkin and Davis, whose campaigns didn’t always see eye to eye, are on a unity ticket when it comes to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people having been frozen out as the debate erupted into a bitter political brawl. “It became the opposition’s argument with the Prime Minister. We weren’t even respected enough as opponents to have a go at us. We kind of got left behind, swept under the table. It became purely about the leader of the government versus the leader of the opposition (Peter Dutton),” Parkin said.

“Some will say, ‘well that’s just politics, that’s just the way that this was always going to go’. But that’s not how this started. That’s not how it was intended. And there is something very telling and dismissive of Indigenous peoples. It was very demeaning.

“I would have preferred that the argument had been had with us. It just didn’t seem like there was a level of respect for us as proponents of this thing.”

Davis, a Cobble Cobble woman and constitutional law professor who read out the Uluru Statement from the Heart on May 26, 2017, said: “We were sidelined. The very core of the Uluru statement was issued to the Australian people because politicians never fare well on Indigenous policy because we cannot dominate the ballot box and politicians are all about the next election,” Davis said. “The Uluru statement was issued to the Australian people. It was an appeal to them. That got lost in the bread and butter adversarial tussle.”

An investigation by The Weekend Australian into the referendum fallout has revealed:

• Internal Yes research showed awareness levels of Indigenous disadvantage only reached 50 per cent by referendum day;

• Albanese received input from Yes23 co-chair Danny Gilbert on the voice proposal he took to the 2022 Garma Festival;

• Yes23 funding vehicle Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition maintained $2.3m in cash and cash equivalents following the referendum;

• Yes23 campaigners and their pollsters at CT Group knew support for the voice was soft even at its mid-60s peak in late 2022;

• After meeting with Dutton in February 2023, referendum working group member and Indigenous activist Marcia Langton declared he would break bipartisanship; and

• The future of the Morrison-era Coalition of Peaks is being questioned by senior Indigenous leaders who are demanding Albanese not walk away from the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Yes and ALP campaigners realised more than one-month out from referendum day that the voice would likely be voted down but holdout hopes of a close result. The Weekend Australian has confirmed a possible delay was raised in discussion among referendum working group members but it was clear that once Albanese pulled the referendum trigger, he was never open to delaying the date.

The downwards trajectory in polling, which began in earnest in April last year, accelerated in the final four weeks as Australians firmed on their positions.

Yes campaigners acknowledge they faced an uphill battle engaging and educating Australians who were dealing with extreme cost-of-living pressures. Coverage of the voice campaign evaporated one week from referendum day when Hamas massacred more than 1100 Israelis on October 7.

Some Indigenous campaigners lament that the formidable ALP and union election machines never really kicked into gear.

The longer the campaign ran, federal Labor MPs “did the bare minimum to help” and left a struggling Albanese to hold the can. While voice campaigners variously described Labor politicians as “hopeless”, “not up to it” and “useless pricks”, another said Albanese had been upfront that “it was our campaign to win or lose”.

Davis said Labor was now effectively endorsing the Morrison government approach of shifting responsibility for Indigenous affairs to states and territories, who were opting for inaction on deaths in custody and advancing “tough on crime” policies.

“Policies in the post-referendum environment suggest the states and territories think it’s a free for all; it’s a ‘no’ to anything,” Davis said. “The commonwealth isn’t doing enough, the states and territories aren’t committed … The Federation is replete with regulatory ritualism where governments espouse commitment to Indigenous wellbeing and advancement but their actions demonstrate this is not true.”

Alarm bells

Yes23 campaigners and their CT Group pollsters knew support for a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous voice to parliament was soft, even at its mid-60s peak in late 2022.

More concerning was the lack of awareness or acknowledgment among voters that Indigenous people suffered from disproportionate disadvantage. It meant the reason for the voice was not accepted.

The Weekend Australian can reveal internal research showed awareness levels of Indigenous disadvantage did not reach 50 per cent until referendum day.

Adding to the challenge of educating Australians about conditions faced by Indigenous Australians, particularly those in regional and remote areas, was that only about 3 per cent of non-Indigenous voters had direct engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

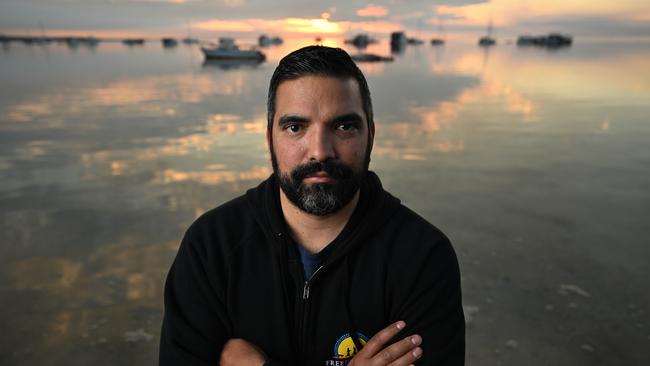

“We’re out there selling a solution to a problem that 50 per cent of the country didn’t know existed or didn’t believe existed,” said Parkin, a Quandamooka man from Minjerribah. “I’m pretty sure at the beginning, one of the polls … said it was about 15 per cent of people who agreed there was Indigenous disadvantage. You’ve got low levels of connection to people. You’ve got low awareness of the problem. So generally, you’ve got a low level of salience in your own life about the connection to this issue at a time when interest rates are starting to go up, cost-of-living is starting to rise and inflation is starting to rise.”

Davis and Pat Anderson co-convened the Uluru Dialogue which ran information sessions in CWA halls and council buildings across the country. Those sessions were effective in helping small numbers of people at a time to understand the genesis of the voice and an opportunity for undecideds or againsts to ask questions. It was slow and labour-intensive. Davis said: “We didn’t have enough time to talk to the Australian people and educate”.

Unlike the official cashed-up Yes23 campaign, the Uluru Dialogue, which launched the John Farnham “You’re the Voice” ad, had limited recognition among voters as it focused more on grassroots education workshops.

“Our research, commissioned post-referendum, shows a large proportion of the population don’t know about the Uluru Statement from the Heart, don’t know about the deliberative dialogues that led to the statement or the decade of recognition work,” she said.

“This is deeply worrying but it also indicates to us the work that needs to be done. And fortunately we have 6.2 million extremely enthusiastic and committed Australians (who voted Yes) who want to help us yarn to our No brothers and sisters. That’s not insignificant. It’s the biggest social movement in Australian history. We aren’t done.”

Responding to critics who say “you raised so much more money than the No case … you should’ve had a different result”, Parkin said: “We might have needed a lot more money than what we actually had, especially with those low levels of awareness of disadvantage … we were educating and campaigning at the same time.”

Yothu Yindi Foundation chief executive Denise Bowden, who was Garma Festival director for 12 years before handing over responsibilities ahead of this year’s event, said the referendum “wasn’t won or lost in the margins; it was a resounding and emphatic rejection of the proposal”.

“The challenges faced by many Aboriginal people – especially those in remote communities – are not well understood by most Australians, and that hindered the campaign,” Bowden said.

‘Gaslighting’

Unencumbered by not having to manage a diverse mix of activist, Indigenous, union and other groups, the No campaign adopted a simple operating model and consistent messaging.

The No camp – powered by conservative activist group Advance and led by Indigenous Northern Territory Nationals senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Warren Nyunggai Mundine – co-ordinated weekly with Dutton, Liberal HQ and the Nationals on resources and campaign strategy.

No campaigners seized on a lack of settled detail about the functions and composition of a voice body and whether its powers could extend to the Reserve Bank, Centrelink, Defence and beyond. Provocative historic and contemporary comments by Indigenous leaders, including unionist Thomas Mayo and Langton, were weaponised by No campaigners who ruthlessly disseminated materials via platforms including TikTok, Facebook and Instagram.

Yes supporters point to mistakes – gaffes by Indigenous leaders, Albanese’s refusal to pivot or provide more detail and confused messaging by competing camps – as contributors to the voice defeat.

However, most blame what they describe as one of Australia’s most “ruthless misinformation campaigns”. Davis – who alongside Noel Pearson has been a long-time supporter of meaningful Indigenous constitutional recognition – said she was “living in a parallel universe whereby this thing I’d worked on for 12 years was captured by politicians and people of bad faith and there was nothing we could do”.

The UNSW pro-vice-chancellor and Harvard Law visiting professor said the “story of the referendum matters and history matters”. “Indigenous peoples need to tell their story,” she said. “Our people are still grieving. Australia is not what we thought it was. Many people experienced unfathomable racism that to this day no one outside of our community wants to speak about.

“Slowly it’s dawning on people, especially the government how detrimental misinformation is to public debate. The lies and nonsense about what the voice would do or could do was impossible to combat because lying in politics, especially in the 2023 referendum, was acceptable. I remember at Christmas 2022 being rung by radio stations as Advance started their misinformation campaign geo-targeting particular electorates being asked whether the voice would take freehold land away.”

Former Indigenous Australians minister Ken Wyatt, a Beyond Blue board member, said there was strong feeling in Aboriginal communities they had been rejected by fellow Australians.

“Aboriginal people talk to me about not being wanted … they link it to the voice result, not me,” Wyatt said.

Davis said it was problematic to ask simply what’s next and what’s left from the Uluru statement. “That is a zero-sum game,” she said. “The referendum was unsuccessful but failure is a normal part of political life.”

Parkin describes the weaponisation of the Makarrata commission, treaty, land use and control over departments, taxation and defence as ingredients that were “thrown into the soup to confuse”.

“Not even the admission from Warren Mundine – one of the strongest No campaigners – saying he was a treaty man … that even didn’t seem to blunt the argument,” he said. “It’s almost like this inherent gaslighting of Indigenous peoples. ‘Oh, we’ve got the secret 26-page manifesto.’ The secret manifesto that had been publicly available via the Referendum Council website since July 2015. You know, this massive cooker conspiracy hiding in clear view. It was clearly a one-page Uluru statement and not a 26-page statement.”

After Albanese appeared to walk away from Labor’s commitment to Makarrata at this year’s Garma festival, Parkin said: “The full commitment and implementation of the Uluru Statement involves the establishment of a Makarrata Commission. It’s important when we’re talking about commitment to Makarrata and the Uluru statement, we’re talking about an entity, we’re talking about a commission. That’s the government’s commitment. There’s already money set aside to look into that. It may not be this term, we understand the politics, but there is an existing commitment to a Makarrata Commission and that is consistent with the Uluru statement”.

Parkin said labelling Makarrata and reparations as a “secret agenda of blackfellas finally coming to light” was wrong because they were live issues predating an Indigenous voice. “These have been aspirations articulated by Indigenous peoples for decades. For them to be brought out … as some kind of nefarious, hidden, conspiratorial strategy … the master plan by Indigenous peoples to usurp non-Indigenous peoples from their rights in this country … was just utter gaslighting.”

No guilt

The last time many Australians heard from Parkin was at Sydney’s Wests Ashfield Leagues Club where voice supporters gathered on referendum night.

In a speech drenched with emotion, Parkin’s comments about the “single largest misinformation campaign that this country has seen” and those “who voted No with hardness in your hearts” dominated post-referendum coverage.

Hours before, and anticipating an unsuccessful vote shortly before polls closed, Parkin sat alone in a room at Yes23 campaign headquarters and wrote the speech before joining the ABC referendum panel. Watching “devastatingly quick results” coming in from Tasmania, he braced himself before heading to Ashfield.

The results were worse than feared: 60.06 per cent of Australians voted No compared with 39.94 per cent who voted Yes. Almost 70 per cent of Queenslanders and 60 per cent of voters in the Northern Territory rejected the voice. The only jurisdiction to vote majority Yes was the ACT.

Standing in front of a room of weeping supporters, Parkin acknowledged “people of goodwill who had doubts about what this meant”. The 43-year-old, who took two months to come down from an “adrenaline feed that was on full time”, stands “by every single word of that speech … it was truthful, and it’s truthful now”. He bemoans that despite “massive amounts of disinformation”, there is no room for nuance.

“The minute I said those words, they were the things that got taken up. Basically, sore loser campaign director says it’s all about hard hearted people and disinformation,” he said. “I was at pains … to acknowledge that there were people with good hearts that voted No for their own reasons, and that we were unable to provide them with the comfort and the security that they needed to get behind a Yes vote. And I also said that I wanted to speak to the people with hardness in their hearts that voted No.”

Parkin laments that it “got to a point in the campaign that we were almost unable to say that there were people with racist motivations that were voting No and that there were people with hard hearts that were voting No”. “There absolutely were and I encountered them on the campaign trail as did many others, and I’ve encountered them all my life. And I think it was important to call that out,” he said. “As I said in the speech, we’ve never meant you any harm. Through these reforms … we never sought to take away or diminish anything about non-Indigenous people’s experience of this country and enjoyment of their own country.

“I don’t think there’s anything controversial about me saying that there were people with good hearts that voted No. There were also people with bad hearts that voted No and I wanted to speak to them. I don’t feel guilt. In fact, I feel the opposite. I feel incredible pride for what we did, what we stood for and how we did it.”

Parkin was “heartbroken” for large numbers of remote Indigenous Australians through central and northern Australia who voted Yes. “We saw the majority Indigenous polling booths and communities voting Yes very strongly. There’s a lot of talk about black elites … when it boils down to the actual result, it was the remote Indigenous people across Australia that said Yes they want this.”

Fatal blows

Yes campaigners point to two critical moments that defined the referendum result and destroyed any chance of victory: the Nationals and Liberal Party rejections of the voice.

Aware of the historic failures of referendums that did not achieve bipartisan support, Yes23 campaigners recruited veteran Liberal Party figures including CT Group co-founder Mark Textor, former Liberal Party federal director Tony Nutt, former ACT chief minister Kate Carnell and former NSW treasurer Matt Kean. Indigenous leader Sean Gordon and Carnell launched the Liberals for Yes campaign.

Yes23 leadership was aware “we couldn’t just throw in our lot with Labor because the Coalition haven’t done this, and say we’re just going to leave you behind”.

Langton, a veteran Indigenous leader, researcher and public intellectual, was certain by February 16, 2023, that Dutton was striding towards No. On that day, Dutton and his then indigenous affairs spokesman Julian Leeser – a long-time backer of constitutional recognition who would quit the frontbench and campaign with Yes23 – had accepted an invitation to meet the Prime Minister’s referendum working group.

Langton, a member of that group, had been involved in every step towards Indigenous constitutional recognition for decades.

In an email a few hours after that meeting, Langton said what she saw in Dutton that day was the end of a bipartisanship on constitutional recognition. John Howard famously pledged a referendum to recognise Indigenous Australians’ “special (though not separate) place within a reconciled, indivisible nation” in 2007.

“Dutton is killing bipartisanship, and in my opinion, his motive is as simple as shoring up the No voters and undecided voters as electoral collateral,” she wrote.

Langton, who alongside Tom Calma had worked for the Coalition to create a blueprint for a legislated voice, excoriated Dutton that day for complaining no detail existed. The 72-year-old said there had been a long pattern of evasion and diversion since Indigenous people began to ask for constitutional recognition in the final report of the Reconciliation Council in 2000. Langton pointed to what she described as a history of governments “pitching to the racist voters”.

“We have had enough of the whims of politicians treating us as political footballs … Create an Indigenous advisory body then go to the next election with a commitment to shut it down. Because, you know … ‘Aborigines.’ Wink, wink, nudge, nudge. I am trying to think of a government that did not do this and I cannot,” Langton said.

Other working group members had different accounts of Dutton’s intentions, with one saying they had met him several times and he showed “no hint of aggressive opposition to the issue”.

In November 2022, the Nationals party room led by Price rejected the voice proposal months before the government tabled referendum legislation and released its proposed constitutional amendment. Price, a former Alice Springs deputy mayor who entered parliament following the 2022 election, had quickly emerged as a force of nature within Coalition ranks. Identifying as a proud Warlpiri/Celtic woman, Price was a ruthlessly effective communicator. Nationals’ leader David Littleproud swung in hard behind Price, who rejected outright the idea of a constitutionally enshrined voice.

The first signs of Liberal Party cracks emerged over the 2022-23 summer when Dutton released a list of questions about the voice referendum. Several Indigenous leaders said even then they did not predict the force and heat of the opposition ahead.

The Liberal Party’s defeat in the Aston by-election on April Fool’s Day last year changed everything. Four days later, Dutton announced the Liberals would join the Nationals in opposing Labor’s voice referendum. It was a hammer blow for the Yes campaign. Without bipartisan support, the referendum was at extreme risk. Five days later, Leeser quit the Coalition frontbench to campaign with Yes23. After Dutton’s No, Yes23 poll numbers dived again. The slide continued all the way to October 14.

PM’s voice

When Albanese used his 2022 election night speech at Canterbury-Hurlstone Park RSL club to commit to the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full, Indigenous leaders knew they needed to “get their skates on”.

Weeks later when Linda Burney was sworn in as Indigenous Australians minister, campaigners travelled to Canberra. Albanese’s chief-of-staff Tim Gartrell, a long-time advocate of constitutional recognition, tested the thinking of voice campaigners to make sure they were clear on their ambition.

On July 30, 2022, Albanese revealed draft wording for a voice referendum question in his speech at the Garma Festival in East Arnhem Land. He asked Australians: “if not now, when?”. Constitutional lawyers from both sides of politics had worked on proposed words for years though some of the key contributors were not briefed on what Albanese planned to read out at Garma.

The Weekend Australian has confirmed those included in discussions about the words Albanese took to Garma included Gilbert + Tobin managing partner Danny Gilbert, co-chair of the fundraising vehicle for Yes23.

The constitutional amendment put to voters 15 months later was slightly different and appeared to give parliament more flexibility to make laws about the voice than Albanese’s draft did. These words were settled the following March in a marathon two-day meeting in Canberra after months of reporting on tensions and apparent differences of opinion. Constitutional lawyer Greg Craven, a member of the expert panel advising on the words, was concerned that allowing the voice to advise executive government as well as parliament would ensure the referendum would fail.

He claimed there was an “all or nothing” faction in the Yes campaign that would rather see the Indigenous voice to parliament fail if it did not reflect their vision.

On March 21, 2023, with the wording not finalised for Labor’s constitutional alteration bill, Albanese, Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus, Burney and then special envoy for the Uluru Statement from the Heart Pat Dodson sat down with six representatives of the Prime Minister’s referendum working group led by Davis.

The voice’s ability to advise executive government stayed. The draft unveiled at Garma said the parliament would have power to make laws about the voice’s composition, functions, powers and procedures. The final version gave parliament power to make laws about matters relating to the voice including those four things.

After an emotional Albanese unveiled the final, reworked referendum machinery bill alongside Indigenous leaders in the Blue Room, a short walk from his Parliament House office, he exited the room to find Labor staffers lined up along the corridors applauding. Government insiders reflect that it was akin to “claiming victory in a footy match before the whistle is blown”.

Some Yes campaigners said Albanese had been upfront with them about the prospect of the referendum failing. Parkin said: “You can’t try and time the historical moment where you’ve got the right environmental conditions, the right social and economic conditions, with a party … and a leader that’s prepared to put political capital on the line.

“I’ve often been asked, should you have waited? The reality of any change like this is if you see a window open, you have to be opportunistic. You can’t just say, ‘oh, we’ll just let that window close and another one will open’, particularly in Indigenous affairs.”

Wyatt, the first Indigenous person in a federal cabinet, said delaying the referendum would have been against everything he had seen in politics. “Governments are often approached by individuals to change a course of action but once commitments have been made and there is broad agreement, it is highly unusual for a government to withdraw that,” he said. “It was up to all of those involved to campaign to try to get people over the line.”

War chests

Yes23 campaigners began recruiting business leaders, philanthropic groups and prominent Australians, many of whom had been in discussions with them for months and years.

After deductible gift recipient status was granted to the official Yes and No funding vehicles, tens of millions of dollars poured into competing warchests. High-profile backing of the Yes campaign by corporate Australia was attacked by the No side and the Coalition. The No campaign touted itself as a grassroots movement and painted Yes23 as being bankrolled exclusively by big business and the elite.

Following the messy departures from Qantas of Alan Joyce and Richard Goyder, incoming chair John Mullen in June addressed criticism levelled at the airline and other private sector voice donors. “Corporate Australia has done itself a bit of a disservice with … some things like the voice,” Mullen said. “Whether you agree with it (the voice), or you don’t agree with it, the way that corporate Australia went about supporting it, I think has been detrimental to the image of corporate Australia among many, many people.”

Parkin said: “People will have different views … and that’s fine. With everybody that’s recovering from the referendum result, I wouldn’t be surprised if there was some contemplation and consideration about what that support looks like now. But I reckon organisations will be keen to build off that investment.”

Financial reports submitted by Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition to the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission reveal the Yes23 funding vehicle co-chaired by Rachel Perkins and Gilbert retained almost $2.3m in cash and cash equivalents as of December 31. AICR, which listed an end-of-year surplus of about $2.1m, spent almost $48m from $49.9m in revenue drawn from donations, grants, in-kind donations, merchandise and other income.

AEC disclosures show Australians for Unity, the No campaign funding vehicle, raised $10.8m from 17,366 donations and spent $11.8m. Advance, which ran the No campaign, listed $1.32m from 9400 donors. UNSW, which hosts the Uluru Dialogue, raised $11.12m from 1138 donors with $10.3m spent on referendum expenditure. AICR listed 18,278 donors, raising $43.8m.

Closing the gap

Davis points to the Productivity Commission’s February report that found a “voice or political representation chosen by Aboriginal people was integral to Closing the Gap and change”.

The commission has been damning about lack of progress under Closing the Gap signed by all states and territories in 2020. Davis said there had been examples this year of Indigenous people not “being at the table on many laws and policies and many examples of government ignoring the legitimate voice of First Nations”.

“This issue is not going away,” she said. “Closing the Gap is a good example of where things are deteriorating. Many of my colleagues … say governments are not committed to Closing the Gap.”

The Coalition of Peaks – a group now made up of more than 80 member organisations – was established under the Morrison government in 2020 with the backing of states and territories. Under the agreement, the group was effectively made the unelected representative body for Indigenous communities for shared decisions on Closing the Gap measures. The Productivity Commission says this has not happened and there must be “a paradigm shift” from government. Its fourth annual data report published in July found Australia was on track to meet only four of 17 targets by the end of the national agreement in 2031.

Indigenous leaders and others contacted by The Weekend Australian all privately acknowledged the organisations that made up the Coalition of Peaks did important work but expressed concern about its ability to give fearless and coherent advice. One described the it as amorphous. Another said it could not possibly be a voice because the members are almost all CEOs of organisations reliant on government funding.

Fallout

Following the referendum, Indigenous leaders fell into mourning. Many still keep low profiles.

In the wake of defeat, Albanese virtually dropped any reference to the referendum amid concerns about his political standing and perceptions he had dropped the ball on cost of living. The way forward for Albanese on Indigenous reform remains murky.

In a Christmas Day interview last year, he said the voice result was not a “loss for him” because he was not Indigenous and the debate was not about politicians.

Days later at the Woodford Folk Festival in Queensland, Pearson broke his three-month long silence to lament Indigenous affairs was in a worse state than before the October 14 vote and Albanese was “running away” from the problem.

Davis said while it was “hard for people to retain faith”, all of the reasons for a voice remained. “The urgency remains,” she said. “Nothing has changed.”

She said there was no evidence that “it was the wrong proposal or that it was the wrong time or that it would not work”.

“It is a part of the process that opens up a path to the next set of possibilities,” she said. I” think it’s apparent to everyone, including No voters, many of whom espoused devotion to finding a solution and deep concern about the welfare of Aboriginal people, that things are getting worse.”

Bowden, a Tagalaka woman from Katherine, said while it was easy to find fault with the benefit of hindsight, “blame for the defeat doesn’t lie with any one person or decision”.

“The voting map paints a clear picture,” she said. “It was really only the remote Aboriginal communities of the centre, the north and the west who voted Yes, and that points to a deep disconnect between the cities and those living in the bush.”

Bowden said it was “no good looking in the rear-view mirror or getting bogged down in rejection … It’s the people living in these communities experiencing incomprehensible levels of economic and social disadvantage who need our attention, and that’s always been the case from our perspective.”

Parkin, who is in no “rush to jump back in”, knows he will be called back for the next fight and is “prepared to be on a lifelong, emotional journey”.

The Yes campaign elevated a number of young Indigenous leaders, who through the ashes of the voice referendum have emerged as a new generation of flag-bearers for Indigenous reform. Ahead of the federal election, Parkin is urging politicians to refocus on reforms that are “going to make a real change” and progress bipartisan support across more areas. “I would implore the political leaders, those that are responsible for improving the lives of Indigenous peoples, to take a hard look at themselves and commit themselves to … doing better than what we’re doing right now.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout