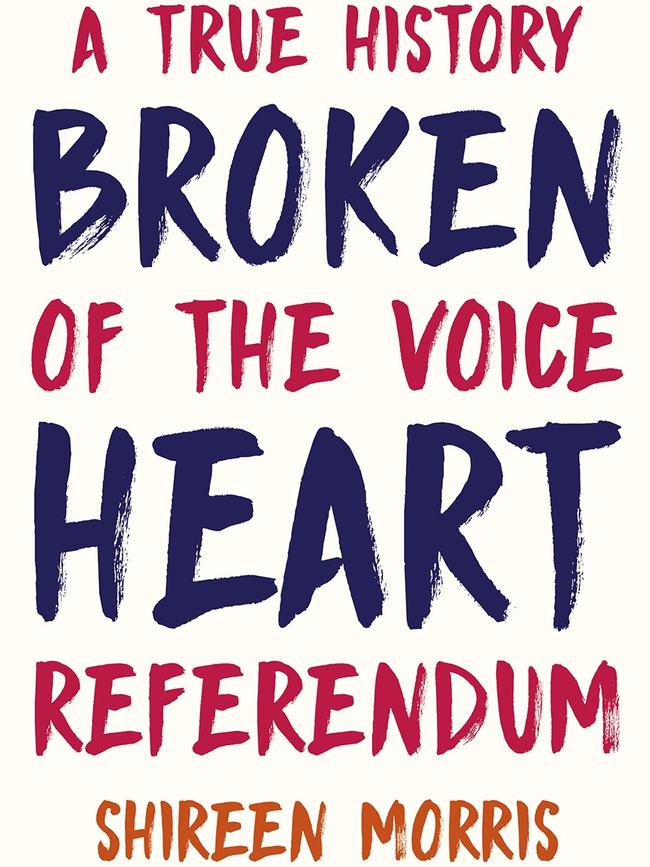

How identity politics killed the Indigenous voice

Shireen Morris’s account fails to recognise where the troubled referendum went wrong.

As a memoir, it is a moving account of Morris’s personal journey, particularly in her engagement with the different ethnic communities across the last 18 months of the campaign. As someone who worked closely with her in the period before that, I am somewhat more cautious of the book’s claim to be a “true history”. In the words of our late sovereign, “Recollections may vary”.

Morris’s greatest contribution to the debate was probably her ability to listen to the concerns raised by constitutional conservatives and to engage with them to find a way forward that addressed such concerns while realising the aspirations of Indigenous people.

These private conversations were a profound instance of what I call in The End of Settlement “settlement politics”. Few people could have played the pivotal role that she played in this process as sensitively and deftly as she did.

She has never claimed to have played anything more than an advisory role (although, to be fair, in the early period her role was far more creative than this suggests). In part, her reason for claiming to be an adviser is a matter of fact. She was employed as an adviser to Noel Pearson at Cape York Institute. In part, her reason for claiming to be an adviser is philosophical: it reflects her commitment to identity politics.

The starting point for identity politics is the belief that there are groups within society that have experienced oppression as a result of political action, and that further political action is required to overcome this oppression.

Most people in Australia would accept that Indigenous people have experienced oppression. Probably most would accept some kind of political action is still required, even if there is disagreement about exactly what action is required.

Identity politics goes a step further, however. It claims that only the oppressed group can determine what political action is necessary to overcome the oppression they have experienced. That means fellow travellers such as Morris can provide advice but, in the end, they need to accept the judgment of Indigenous people as to what action is required.

Morris was not alone in subscribing to identity politics. This was also the approach taken by Anthony Albanese and his government. They maintained that it was for Indigenous people to determine what amendment should be put to the Australian people at a referendum. The Prime Minister was insistent that his commitment was to put to the people the amendment that Indigenous people asked him to put to them.

There were two major problems with this approach. First, it makes sense only to people who have a prior commitment to identity politics. Anyone who is not committed to identity politics will feel entitled to ask, “I know this is the action that the oppressed group has requested, but is it the best action? Will it enable them to overcome the oppression that they have experienced?”

To someone who is committed to identity politics, these questions are immaterial. All that matters is that the oppressed group has made a demand as to what political action should be taken to overcome the oppression. It is for everyone else to accept their judgment.

The second problem is that, in this case, the political action involved a referendum in which all adult citizens would vote. It was far from clear that all these people were susceptible to the arguments of identity politics. Some were, but it was obvious from the outset that a wider section of the electorate would have to vote Yes for it to get up. It was never likely that this could be achieved unless there was bipartisan support for the proposal.

Pearson was fond of saying that Nixon must go to China, and it was in this spirit that Morris and I worked together to persuade a conservative government to find a proposal it could support at a referendum. This is the subject of her first memoir, Radical Heart. Clearly, we failed in our efforts and it fell to a progressive government to put the proposal to a referendum.

When the government changed, the game changed. The progressive government’s priority was to understand what the Indigenous advocates sought the government to put to a referendum, and to make the case for voting Yes to this proposal.

This is hardly controversial from an identity politics perspective. It did mean, however, that no real effort was made to go about identifying a proposal in a bipartisan fashion. The danger was always that if a progressive government put forward a proposal as government policy without having developed the proposal through a bipartisan process, a conservative opposition would scrutinise the government policy and reject it.

Given their history of dispossession and discrimination, Indigenous people were seeking some kind of guarantee that the future would be different from the past. In the past, laws were made about Indigenous people that did not serve their interests.

The Australian Constitution gives the parliament power to make laws with respect to Indigenous people. The idea was that the Constitution should require the parliament to hear from these people before it made any such laws in future. In this way, parliament’s power to make laws would not be limited but an obligation to hear the people who would be affected would be imposed on the parliament. I still remain convinced that this basic idea was able to deliver a guarantee that gave Indigenous people reason to believe that the future would be different from the past in a way that was intrinsically conservative.

It was for this reason that Julian Leeser and I formed an organisation, Uphold & Recognise, to foster a conversation about how upholding the Constitution was compatible with recognising Indigenous people in it. Morris worked closely and constructively with Uphold & Recognise for many years. She writes in Broken Heart that she judged that she needed to stop working with Uphold & Recognise after we held a forum in February last year.

Her concern was that we had a session that included Louise Clegg and Frank Brennan alongside Tony McAvoy SC. She objected to the fact we allowed Clegg and Brennan to raise their concerns about the draft constitutional amendment that the Prime Minister announced as a “suggestion” in a speech at the Garma Festival the previous year but that was not yet government policy.

Morris believed we should have put up only speakers who made the case for supporting the Garma amendment.

Our view was different. We believed it was legitimate to offer a critique of a proposal that was not yet even government policy, provided that some alternative was advanced by anyone offering a critique. We wanted to show that it was still possible to discuss alternative approaches in the hope of arriving at something that could achieve bipartisan support.

We also had Leeser, the opposition legal affairs and Indigenous Australians spokesman, and senator Andrew Bragg speaking at the forum. They were the two most supportive Liberal parliamentarians, yet both of them expressed significant caution in their speeches. Both of them could see that their colleagues were not on track to support the Garma amendment.

Given how little support there was on the centre-right even in principle for an amendment to the Constitution that would recognise an Indigenous voice, we took the view that we needed to have a broader conversation.

We needed to create an opportunity for people on the centre-right to come together and talk about what they could support. We believed that if we didn’t give people on the centre-right the opportunity to talk about what they might be able to support, they would concentrate all their energy on explaining why they couldn’t support the Garma proposal.

No one thought the government or the opposition would support an approach that was rejected by Indigenous advocates.

However, it was our view that more needed to be done to hear concerns and find a way that worked across the political spectrum. That might mean talking about options that were not the preference of the Indigenous advocates. But starting that conversation, we believed, might bring people closer to something that they could live with.

I understand why this approach was totally mistaken from the perspective of identity politics. But the people we were trying to talk to didn’t accept identity politics. Leeser and Bragg both tried to encourage the government and the parliament to consider other approaches that some of their colleagues might be able to support. There was no interest in this.

I look back with pride at my role in the work Morris discusses in her first book. I lament the direction that this debate took. A decade ago, it still seemed that a settlement was possible. Alas, history has shown that it was not.

Politics became increasingly polarised, with identity politics asserting itself on the left and populism taking hold on the right.

Morris and I believed that it was possible to find common ground but, over time, it became increasingly difficult for us to work together in pursuit of this common ground. I hope that in future more people will commit themselves to working with people who see things differently, and that Australian society and politics will become less polarised. Perhaps that will pave the way for mending some of the hearts that were broken so badly last year.

Damien Freeman is a fellow of the Robert Menzies Institute at the University of Melbourne and an honorary fellow of Australian Catholic University. His most recent book is The End of Settlement: Why the 2023 Referendum Failed.

There were plenty of broken hearts on the morning of October 15 last year, but none more so than that of Shireen Morris. Yes, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people felt the pain uniquely, but Morris’s broken heart was that of someone who had campaigned tirelessly for more than a decade for a cause that would not give her any personal benefit. So I can understand why her memoir is published under the title Broken Heart.