How Australia got it so wrong on the Indigenous voice

From the moment the results of the voice referendum started coming in, politicians, advocates and commentators have been trying to rewrite history. The truth? Ultimately, the political right chose not to play ball.

From the moment the results of the voice referendum started coming in on October 14, 2023, politicians, advocates and commentators have been trying to rewrite history.

Pundits called it a “no compromise” referendum. Its failure was the fault of Indigenous leaders and the Labor government who, we are told, stubbornly refused to negotiate or compromise.

According to The Australian, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese had to take responsibility for his government’s mistakes in managing the referendum, while Indigenous leaders needed to “accept their own part in insisting Mr Albanese take the toughest possible stand on the referendum question”.

The whole referendum approach was described as being “crash or crash through” – this phrase was repeated ad nauseamduring and after the campaign. The Labor government and Yes proponents were “pig-headed” and this led to defeat.

This narrative is false, and inverts reality. It points the finger solely at Labor and Indigenous leaders for failing to find common ground with the right.

It exonerates the Coalition for its refusal to negotiate with Indigenous leaders who wanted more than empty symbolism and, ultimately, the Coalition’s politically motivated choice to kill the voice referendum.

Indigenous leaders repeatedly compromised to try to win Coalition support. The Coalition never compromised. The right’s failure to meet Indigenous people in the middle cruelled the referendum and, with it, hopes of achieving Indigenous constitutional recognition. Peter Dutton and the Coalition must wear that legacy.

The “crash or crash through” narrative was true only in one respect. As the campaign proceeded, its momentum became unstoppable. It became a freight train, hurtling forward with the force of its own velocity. In earlier years, I had always thought the government in charge would pull the plug if polls showed certain defeat. Yet in the heat of battle, with election promises made, advocates committed, donations received, the date set and hearts on the line, pulling the pin seemed impossible.

The compromise voice proposal, devised with bipartisanship in mind, needed to either float or sink. Australia needed to see itself. And now we will.

-

Let me address the perspective from which I write. I occupy a strange position in Indigenous and Australian politics. I am neither Indigenous nor white. My ancestors hail from India, via Fiji, where the British took indentured servants to work on sugar cane plantations. My parents migrated to Australia in the 1970s, towards the end of the White Australia policy. Though I was born here, my migrant ancestry is one perspective I brought to the referendum debate.

I am also a constitutional lawyer whose primary focus for over 12 years, under the mentorship of Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson, was Indigenous constitutional recognition.

Some will say a non-Indigenous person shouldn’t have been involved in Indigenous constitutional recognition at all. The contemporary trend is to critique who gets to speak, rather than engaging with the speaker’s argument. An Indian Australian can talk about multiculturalism, but not Indigenous recognition.

It was a political reality that the Indigenous three per cent minority would need supporters and advocates from the 97 per cent to achieve their desired reforms.

The Uluru Statement invited non-Indigenous Australians to “walk with” Indigenous people because the country cannot be healed, and the Constitution cannot be changed, by the three per cent alone. As Palawa elder Rodney Dillon observed in 2018: “We’ve been flat out campaigning for the last 200 years. We’ve done well in some places but not well in other places … I think that non-Indigenous peoples’ support and influence can be really, really important to make change.”

I took that responsibility seriously, but identity was a hindrance. The observation that “Shireen is not Blak” was sometimes posted or noted in response to my advocacy – sometimes by the same people calling for solidarity with Indigenous causes. The chastisement was not generally applied to the many white constitutional lawyers and advisers involved, perhaps because their non-Blakness was more self-evident. White experts and lawyers seemed revered and respected, whereas non-Indigenous, non-white involvement required special justification (and so) I floated around the edges, in-between and often unseen. I advised Noel Pearson, co-wrote submissions and joined meetings with him, and continued to advocate and persuade, but in later years I was not a key player, strategically speaking. Still, invisibility allows a different perspective and perhaps some objectivity.

-

Noel Pearson and I always believed that if we worked with conservatives and created broad coalitions for change, then with hard work and perseverance, a double majority of Australians could be persuaded to vote Yes to a constitutional voice for Indigenous peoples. We had no illusions about the difficulty of this challenge. In the end, the voice referendum did not win a majority in any jurisdiction except the ACT. The failure was comprehensive.

The key killer was lack of bipartisanship, long considered a prerequisite for referendum success. But in an era of sharpening political polarisation, social fragmentation and tribalism – exacerbated by social media’s amplification of disinformation, hate and dumbed-down debate – sensible cross-party policy discussion conducive to bipartisan reform ultimately proved elusive.

Though the voice germinated in collaboration across divides, the referendum became a partisan war zone, with politicians opting for political point-scoring rather than co-operation for the national good.

Why did Indigenous leaders and the Labor government persevere with the referendum absent bipartisan support? To put things in perspective, Indigenous people had been waiting 122 years for a government willing to put worthwhile constitutional recognition to the people.

Genuine bipartisanship may never have been forthcoming given the Coalition’s longstanding resistance to anything other than constitutional symbolism.

Lack of bipartisanship notwithstanding, the voice was still viewed as the best chance of finally recognising Indigenous people in the Constitution in the way they wanted to be recognised, and in a way that would deliver tangible improvements to Indigenous communities.

As voice campaigner Thomas Mayo reflected after the referendum was defeated: ‘I don’t have regrets … It was something Indigenous people wanted …. We had to try because this is an urgent matter.’”

They had to try.

I watched the proposal become a political football. I saw first-hand how our radical centre coalition with constitutional conservatives faltered and then fractured under political pressure. The nasty tribalism of our politics ultimately could not be overcome.

In the final few months leading up to the referendum, I was flying around the country to speak at events. I visited Indigenous communities and was reminded how much this meant to them: the urgency of the need for change was palpable. There were communities up north where kids were known to break into houses, not to take laptops or mobiles, but to take food from the fridge. It made me think of my own son: I couldn’t fathom him facing such deprivation.

Those remote Indigenous communities voted Yes in the highest numbers. Their need was greatest. After weathering the cruelties of history, they desperately wanted reform and reconciliation, and were reaching out to their fellow Australians for love and acceptance.

But they were not the focus. The debate I witnessed was mired in polarisation, disinformation, confusion and racism. I heard claims that voting Yes would allow Indigenous people to take away our backyards. That voting Yes would force businesses to give stuff away to Indigenous people. That voting Yes would mean we would all have to pay rent for living on Indigenous land.

None of this was true. Yet these claims went viral on social media and were whispered to voters at the polls.

The referendum was an opportunity for a national settlement of historical wrongs. The problem was many Australians probably did not see this as a settlement of our nation’s troubled history. The historical context was missing. Many Australians voted No in a context vacuum.

Identifying and unpacking mistakes is crucial if reformers are to learn from the referendum’s failure. But acknowledging strategic missteps does not exonerate the Coalition. Ultimately, the political right chose not to play ball. They chose to oppose a modest proposal for Indigenous recognition instead of owning and refining it. The Coalition should have made the voice its own while in government, especially given the concept was co-created with conservatives.

The Coalition should have continued that collaboration with Indigenous people and led a “Nixon goes to China” referendum. Instead, it shirked that historic opportunity for leadership, and when Labor finally took the reins in 2022 it chose to sow division for political gain. The Coalition wanted to derail the referendum to hurt Albanese. Indigenous people were cannon fodder in the ensuing partisan war.

Acknowledging failures on both sides of politics cannot completely exonerate the Australian people for the choice we collectively made. At the end of the day, we decided. A significant majority of Australians voted No based on the information we had before us. We had the Yes and No booklets. We heard the basics of what was proposed. Whether we chose to seek out the facts or rely on lies was our choice. We exercised our democratic rights. Australians, too, must wear that legacy.

I don’t accept the truism, repeated by politicians after the defeat, that “the Australian people always get it right”. The quip incorrectly insinuates that anyone who respects democracy must endorse all outcomes of democratic processes. It reveals political cowardice: “I’m too scared to acknowledge that Australians made a poor decision in rejecting the voice, in case they reject me too, so I’ll pretend they got it right.”

I take a contrary view. The Australian people, acting through our democratic procedures, do not always get it right. We did not get it right when our policies and laws enabled Indigenous Australians to be paid unequal or non-existent wages during the protection era, nor when our democratically endorsed decisions sanctioned the forcible removal of Indigenous children from their families, the banning of Indigenous languages, and the denial of Indigenous property rights. We did not get it right when we enacted legislation that denied Indigenous Australians the vote in some jurisdictions right up until the 1960s.

The Australian people got it wrong in the voice referendum. We chose fear over love. Though voting Yes would have cost us little, we fell for nitpicking and division over a chance at reconciliation.

That was our right: our collective decision was, of course, democratically legitimate. But we made a mean and miserly choice. The ask, after all, was small.

After everything Indigenous people have been through in this country – the discrimination, the dispossession and the bloodshed of the past – all they were asking for was a guaranteed advisory voice. Theirs was a hand of friendship extended, asking only for the ability to have a say in decisions affecting them, and we slapped it away. We couldn’t find it in ourselves to give them even that.

We can reflect that Australians were misinformed or confused or distracted, that the Yes campaigns were ineffective and the No campaigns too effective, that social media favours lies and hate, and that lack of bipartisanship killed it – and that may all be true. But these are also excuses. Whatever the myriad reasons for failure – and we must learn from them – Australians said No to our nation’s best opportunity to settle our fraught founding history. The chance to achieve Indigenous constitutional recognition has been lost, likely forever. I know many Indigenous people will be experiencing pain for a long time.

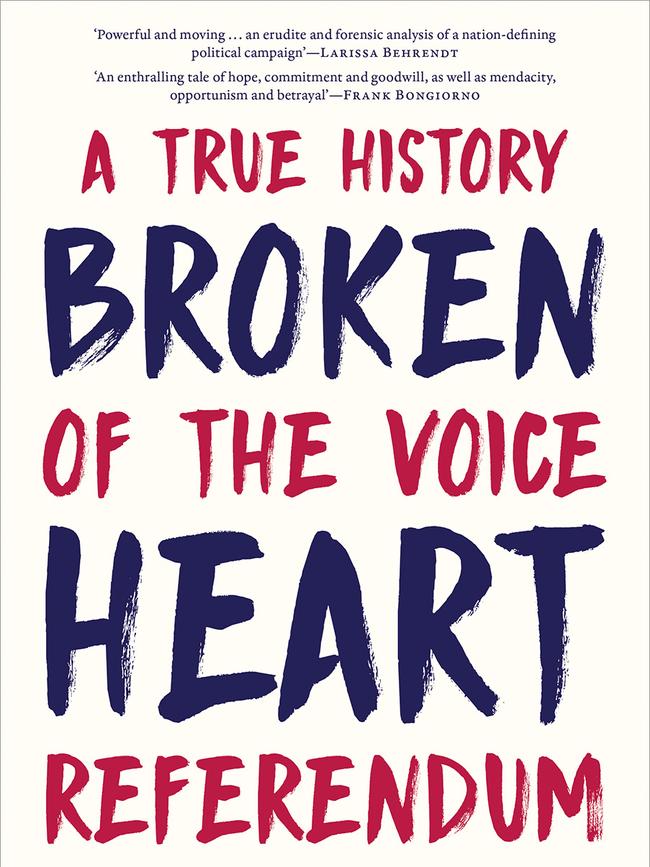

This is an edited extract from Broken Heart: The True History of The Voice Referendum, published by Black Inc on August 19. The author, Shireen Morris, is director of the Radical Centre Reform Lab at Macquarie Law School, and a former Labor candidate for the Federal seat of Deakin.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout