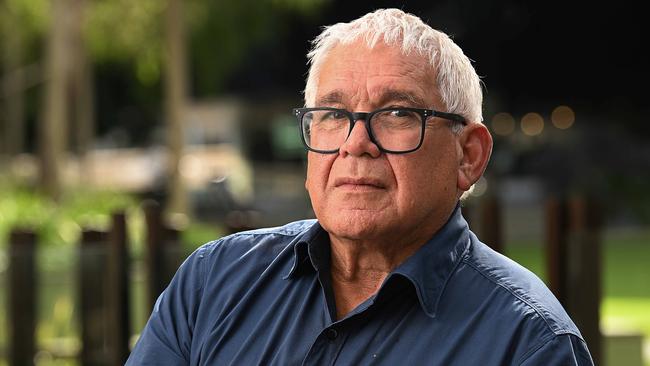

Yes campaign crash: Mick Gooda’s anger at Anthony Albanese’s voice strategy, and aftermath

Indigenous leader Mick Gooda has hit out at the PM and Yes campaigners for their refusal to amend the proposal after it failed to win bipartisan support.

Indigenous leader Mick Gooda says Anthony Albanese and prominent Yes campaigners are responsible for the failure of the voice referendum, hitting out at their refusal to amend the proposal after it failed to win bipartisan support and began tanking in the polls.

The former human rights commissioner will use a speech on Friday to attack the “crash or crash through” approach taken by the Prime Minister and his party on the advice of campaigners such as Noel Pearson, declaring he was “angry with the Yes side” over the outcome.

Mr Gooda will accuse Labor of being “stuck in some form of paralysis” since the voice referendum and is critical of the government for its failure to outline a new plan on Indigenous affairs.

“So here we are, four months after the referendum and at the federal level things seem to have come to a complete standstill,” Mr Gooda will tell the Aboriginal National Press Club in Brisbane on Friday, according to a draft copy of the speech.

“It’s almost as if some form of paralysis has taken over. I have heard of vague rumours that some local or regional structure will be established; we have heard the Prime Minister’s Close The Gap statement last week about more jobs in remote Australia and a revamped Community Development Program; but what we are not seeing is a narrative, a vision of where we go to from here,” Mr Gooda says.

He laments why the normal rules of politics were ignored in putting the voice proposal to a referendum.

Mr Gooda says he does not understand why the Yes camp and the government pushed ahead with their model despite the absence of “key ingredients” such as bipartisan support and detail for voters.

He says the government should have pursued bipartisanship by proposing a legislated voice as recommended by the report to the Morrison government by Indigenous academics Marcia Langton and Tom Calma.

“I am angry that we knew these things but for some reason we went with a ‘crash through or crash’ approach,” Mr Gooda says.

“Some people describe politics as the skilful use of blunt objects, while others talk about politics being the art of compromise.

“Let the record show in the referendum, we most certainly crashed.”

In a key intervention ahead of the referendum last year, Mr Gooda said he was terrified the proposed constitutional change would fail and urged advocates to look at ways to arrest the slide in public support, such as removing “executive government” from the amendment’s wording.

His comments earned him a rebuke from Mr Pearson, who accused Mr Gooda of “wetting the bed” and described his behaviour as “extremely foolish”.

Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus proposed watering down the power of the voice to provide advice on executive government – effectively limiting the ability of the proposed body to advise cabinet – but the Prime Minister rejected this on the advice of Mr Pearson, Megan Davis and other members of the referendum working group.

Mr Gooda, who is spearheading Queensland’s truth-telling and treaty-making processes, says the government failed to ensure it had the three “key ingredients” needed to win the referendum.

“The first is bipartisanship between the major parties (which) is the most essential ingredient for a successful referendum,” he says.

“The second essential thing is a human reaction … and that is, if we don’t know what we are voting for, we will generally vote no.

“The third thing we know about referendums is that there is a high point of support for the question and this usually comes a fair while before the question is put to the people and once that support begins to slide downward, it never returns to that high point.”

Mr Albanese said on Thursday no member of the referendum working group – a panel of 21 Indigenous leaders advising on how to proceed with the voice referendum – had suggested to him the voice should be legislated before the referendum was held.

“In 2019 as well as 2022 both sides of politics went to the election saying there would be a referendum on constitutional recognition,” he said. “The form of constitutional recognition was through a voice to parliament. That was the request; we honoured and respected that request of First Nations people; we respect the outcome of the referendum.”

Sean Gordon, a member of the referendum working group, said there had not been any discussions over whether the voice should be legislated instead of enshrined in the Constitution, but this was because Mr Albanese had “locked in” the model at the election. “He locked it in; it didn’t allow for those conversations to be had,” he said.

Mr Calma confirmed no such discussions had taken place.

Rather than arguing the voice should first have been legislated – as Professor Langton has done this week – Mr Calma says his only criticism is the time between the referendum date being called and Australians casting their votes might have been too short.

In his speech, Mr Gooda urges the government to put forward “a vision of where to go from here” that goes beyond Closing The Gap statements. Mr Gooda echoes comments by other Indigenous leaders such as Professor Langton and Mr Gordon in urging for local and regional voices to be looked at as a possible path forwards in Indigenous affairs.

When asked whether the government would explore expanding the local and regional voices model, Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney said last week: “Where we’re at, at the moment, is accepting the outcome of the referendum. Issues like regional voices are something that I know that are being very much discussed in places like the Kimberley … and I’m not going to say anything definitive today – it’s not my job to do that right now.

“They are discussions to be had with the community and within the structures that we need to within this place.”

Ms Burney would not lay out a time frame for such discussions, nor would she clarify if and when truth-telling processes would begin at the federal level.

Mr Gooda will say in his speech that the truth-telling process – at state, territory and federal levels – was not about punishing people, and cautions against the renaming of streets and landmarks because of their fraught history.

On treaties, Mr Gooda says fears of compensation being demanded out of negotiations between government and Indigenous people are misplaced.

“At the most fundamental level, a treaty is an agreement that is negotiated between at least two parties,” he says. “If one of those parties does not agree with a particular matter being included in a treaty and that position cannot be mediated, then one of two things can occur. Either, the matter in contention is not included in any treaty or ultimately there may not be a treaty at all.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout