Forget Jim Chalmers, Michele Bullock, the RBA boss he appointed, is sitting in the economic policy driver’s seat

Jim Chalmers is a busy and fluent communicator, always ready to take the talking points out on a leash for a morning run. He has a disciplined short game and freewheeling long game, but is forever trying to land a linguistic hole in one. Enter Michele Bullock.

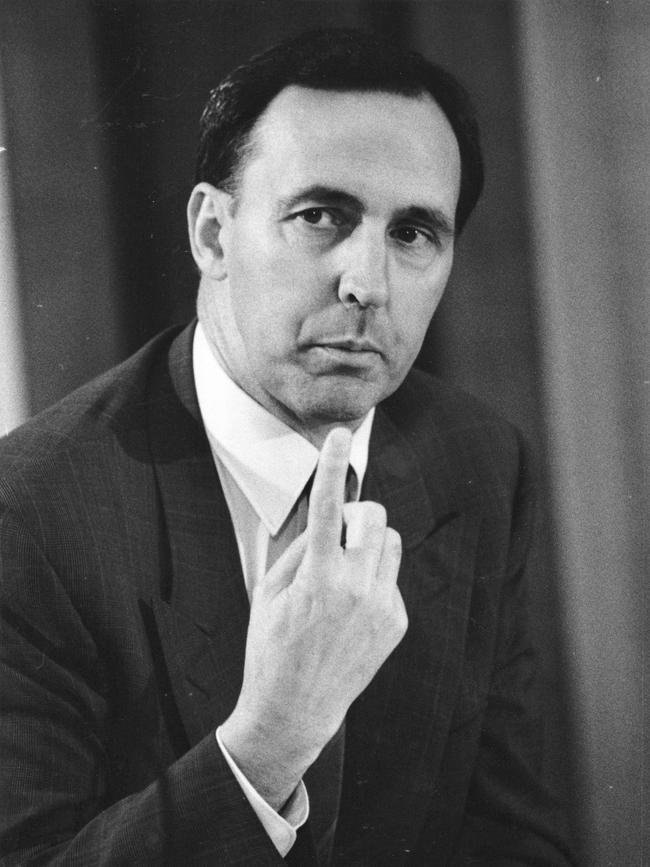

Paul Keating schooled a glittering cohort of Canberra journalists in the 1980s about policy and politics, and through them, the public about what was holding back Australia from realising its economic potential. The Labor disrupter, with his urbane eccentricities, didn’t hog the media space through the volume of his utterances, as today’s neurotic players are wont to do.

Keating embodied his convictions; a man possessed by narrative, he claimed authorship of a bigger story for our people and was born to argue for it. Plainly, the 80-year-old hasn’t stopped crusading or tutoring; it’s more likely he’ll burn out, than fade away.

I was late to the reform party, and based safely in Sydney, so Keating did not colonise my brain. But he certainly created the space for deeper engagement about economics with my editors and readers because he was also unshakeable.

It wasn’t simply a matter of colourful language during raucous question times and at the boozy press club; there was action in the parliament, momentum in the bureaucracy, debate within the caucus. The policy scoreboard kept ticking over.

In time, John Howard and Peter Costello would take over the business; like tune-up mechanics, running an orderly workshop with good accounting hygiene. Then China came along and the enterprise was generating so much cash the family trust could barely cope with the money flow. But the two Liberals did take up with gusto one theoretical no-brainer, which carried immense political risk: a goods and services tax.

Early in its term, the Coalition began preparing the ground for what would become A New Tax System, with the GST at its centre and all revenue going to the states; Howard lost most of his electoral buffer in 1998 and part of the GST’s initial design as he negotiated with the Australian Democrats.

Still the country was better off for the conversations and a well-managed process delivered what Costello claims was “an absolute blockbuster”. “It was the biggest tax change ever,” the former treasurer told author and former Treasury official Paul Tilley.

Maybe. There’s a limited field of runners. Still, since the Keating era every federal custodian has talked tall, but delivered small.

Jim Chalmers is a busy and fluent communicator, always ready to take the talking points out on a leash for a morning run. He has a disciplined short game and freewheeling long game, but is forever trying to land a linguistic hole in one. But to what end?

Lately, Chalmers has regressed to his inner defensive, micromanaging ministerial staffer. It’s also true of the operating style of other executives in the Labor show who were reared in the Rudd-Gillard years of messaging total control, but his interventions have greater consequences.

The Treasurer looks to get ahead of the economic story, often distributing lines before an event or major statistical release. But these strikes can backfire. Ahead of the June quarter national accounts, published earlier this month, Chalmers’ office provided “preview lines” on a Sunday with a 10.30pm embargo.

“With all this global uncertainty on top of the impact of rate rises which are smashing the economy it would be no surprise at all if the national accounts on Wednesday show growth is soft and subdued,” the Treasurer said.

Chalmers had previously ventured into this verbal terrain but this time hardened his language. It raised the temperature ahead of news that would, most likely, hurt the government. By putting the Reserve Bank in the frame for causing misery for households through elevated interest rates, he also implicitly downplayed the role of the real culprit – high inflation.

For good measure, the Treasurer also spoke about understanding “pressures on people in an economy already being hammered by higher interest rates and global volatility”.

And furthermore: “This is precisely why it’s so important our economic plan is all about fighting inflation without smashing an economy which is already weak.”

Inexplicably on the eve of a sitting week, slow horses in the media missed the story – but the central bank did not. Insiders and past officials viewed it as an assault on the bank’s independence and an attempt to put pressure on the RBA to cut interest rates, to boost the government’s political stocks.

The “firestorm”, as one tabloid editor, who didn’t detect the smoke put it, was made worse by the freelance contribution of Wayne Swan; on the day Anthony Albanese was launching an initiative to address domestic violence, the ALP national president said the bank, led by a woman, was “punching itself in the face” on inflation. The opposition used the episode as an excuse to ditch its support for Labor’s legislation to establish, among several changes, a new interest rate-setting board.

Government operatives often appear to have no other settings in the dark arts than siege, catch and kill, ignore, distract. Persuasion, building trust and a knowledge base are just too risky, too hard, too old-school, even for seasoned ministers.

“Crisis comms comes to Canberra” is not a new story. Neither is bypassing the press gallery and going straight to the people, be it via the spangled FM band or the helter skelter socials.

That approach, however, abandons nuance and complexity; it leaves a void in messaging during the cost of living squeeze and as the economy goes ever deeper into a monumental structural adjustment, which is the transition away from fossil fuels.

More worrying, however, is the absence of an economic story; if it’s there, it’s muted, like a backing hum of “feels”. I understand what the government wants for itself, but what does it want for the country? Ditto for the other retailer in our political oligopoly.

Yet this gifted space is where Michele Bullock, a year into a seven-year appointment as RBA governor, and her senior executives are making their mark. This diligence is due to both circumstance and design.

The RBA is playing the leading role in short-run economic management through the instrument of its cash rate; its mandate is to keep inflation low, trying to hit the 2.5 per cent midpoint of its target band, on average, while aiming to keep as many people in jobs as possible.

Bullock is in the policy driver’s seat while inflation is the “main game”. Chalmers claims his budget settings are helping to get inflation down; cheaper childcare, medicines and education fees, as well as rental assistance and energy bill relief are easing the strain on households. But he’s delivered two budgets in a row where spending growth is pumping up public demand, which is counter to the RBA’s mission.

Since last November, the RBA board has kept the cash rate at 4.35 per cent, trying to get demand and supply in better balance, to bring inflation down over a reasonable time. Bullock has said this realignment is now taking longer than expected, with a burst of public spending on social services, bureaucrats, care sector workers and “big builds” a factor keeping rates higher for longer.

This holding pattern presents risks. What do you say when the signals are mixed and there are long lags in the way interest rate settings work their way through the economy? You say very little, because so-called forward guidance during the pandemic hurt the RBA’s reputation (and ended the career of its previous chief). But you still have to sound like you know what you are doing.

Deputy governor Andrew Hauser made a virtue of this uncertainty in a speech last month, admonishing the “false prophets”, while inviting blow back from these self-appointed gurus. “When the stakes are so high, claiming supreme confidence or certainty over what is an intrinsically uncertain and ambiguous outlook is a dangerous game,” he told an audience in Brisbane.

“At best, it needlessly weaponises an important but difficult process of discovery. At worst, it risks driving poor analysis and decision-making that could harm the welfare of all Australians.”

The independent review into the central bank called for a revamp of communications; the governor now conducts a press conference after every board meeting, while senior RBA officials have embarked on a monetary policy education blitz. Assistant governors have spoken about how monetary policy is transmitted, the journey to full employment and financing innovation.

But it’s Bullock that commands centre stage. On the evidence to date, the governor is authentic, confident in the territory, measured, direct and clear. She has established herself as a person of authority and is trusted, even as she continues to deny the hungry multitude a cut in interest rates.

The day after the June quarter national accounts showed the economy was spinning its wheels, Bullock detailed how high inflation was the real enemy to our prosperity; the disease, which hurts everybody, was far worse than the painful cure of elevated borrowing costs.

At Tuesday’s press conference, she spoke about the nation’s need to raise productivity growth so the economy could sustain higher wages without igniting inflation, produce more and, over time, raise material living standards.

Bullock also made a pre-emptive strike of her own, a day before the release of monthly inflation data. These figures provide a limited picture and are notoriously volatile; they were expected to show an annual headline rate inside the target band (the result was 2.7 per cent for the year to August due to temporary energy bill relief by Canberra and the states).

The RBA is preoccupied with the “trimmed mean” measure of underlying inflation, which removes the outlier items from the consumer price index. “The point I would make is that if tomorrow we get an inflation number with a two in front of it, so it’s back in the band, that doesn’t mean that we’ve got inflation under control,” Bullock told reporters. “It doesn’t mean that inflation is sustainably back within the band.”

The headline rate is going to dip in and out of the zone over the next 12 months, but underlying inflation won’t be back inside the band until the December quarter next year. Australia is getting closer to a turning point, but we’re not where other central banks are, like the US Federal Reserve and Bank of England.

Those peer institutions have started to cut interest rates because of clear signals that inflation has been tamed and there’s a present danger of a rapid rise in unemployment. Short of some calamity, most likely due to global events, many economists believe the RBA will cut the cash rate at its first meeting next year, in mid-February; markets have herded into a view a cut will come at the end of this year.

The verbal sparring among the official family of economic policy, which in this rarefied world amounts to low-level passive-aggressive rhetoric and smiles all-round, will go on as long as the government wants it to go on. But it will come at the cost of public confidence in our key institutions and, eventually, hamper their performance.

The electorate is hungry for better days and would clearly prefer to back in a team that offers solutions to our big challenges and extends the nation’s opportunities. It’s been done before. If it is to survive in office, Labor needs to come up with a more compelling action plan, pivot to a better story and find its voice.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout