Jim Chalmers didn’t need any assistance in beating up on the Reserve Bank. But he got it anyway.

Former Labor treasurer, and Chalmers’ mentor, Wayne Swan has now taken up the cudgels against the RBA.

Swan’s comments went further than Chalmers’. But rather than the RBA punching itself in the face, as the Labor Party president suggested, it is the Albanese government that is at risk of giving itself an uppercut.

This tactical shift to apportion blame for the financial misery many Australians find themselves ignores the duality of responsibility that the central bank and the government must both bear.

Another former Labor minister, Graham Richardson, suggests the bank should not be immune to criticism. In that same spirit, nor should the government be indignant to deprecation of its own role in all this.

Households are about to enter territory uncharted since the last recession. Savings, or the distinct lack of them, will likely become the proxy for the next political battle, as the fall in living standards becomes baked in.

The buffer that the central bank has until recently used to suggest to wage earners that they could survive the rate hikes has evaporated. Households have literally cracked open the piggy bank and there is nothing left to sustain them.

This is not only a result of inflation. The unprecedented tax take by Canberra has helped erode real household disposable income. And it is the savings crisis, laid bare in this week’s national accounts, that should be of growing concern to the Treasurer.

Until now, families appear to have been behaving as though the massive hit to their standard of living was transitory and temporary. And if only they held out, things would return to normal.

Once they realise that this hit to their real disposable income is permanent, attitudes will dramatically shift. And they are likely to shift against the Albanese government.

The very basis upon which the RBA had assumed households would manage the unprecedented rate hikes no longer exists – largely because no one, including the RBA and the Albanese government, believed that the inflation problem would persist for as long as it has.

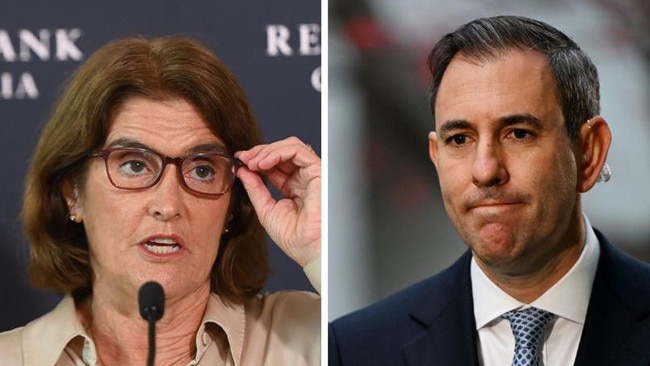

RBA governor Michele Bullock this week warned that some people would lose their homes, were in negative cash flow and were dipping into their savings to sustain their mortgage payments. What savings?

The national accounts numbers revealed that household savings had plummeted to 0.6 per cent from about 6 per cent. The standard accepted by economists that household savings should be between 5 per cent and 10 per cent.

The problem is that households have no way of replenishing those savings considering living standards have fallen almost 10 per cent. Real disposable income has been incinerated.

Bullock says that it is inflation that is the problem rather than rates. This will jar with mortgage holders.

Unless living standards are somehow miraculously restored, households are going to have to further trim their consumption.

Many households may still be living in the hope that their standard of living crash is temporary. Once they realise it’s not, their behaviour and attitude will change.

The big readjustment is coming, and just in time for an election. Whatever light there may have been at the end of the tunnel for many people, has faded.

Once this reality sets in on voters, the government may cop it. The Coalition is clearly banking on this.

And the sign that permanence is more likely can be found in the critically poor productivity numbers.

As opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor says: “Transitory hits to living standards are tough but manageable, permanent hits are cathartic.”