Former PM Paul Keating on why the west has reached ‘cultural exhaustion’

Paul Keating takes us through his personal collection of art and antiquity – and explains why he believes the West has reached a point of ‘cultural exhaustion’. The former prime minister has never done an interview quite like this one.

AESTHETE n. a person who has or professes to have a special appreciation of beauty. [From Greek aisthetes, ‘a person who perceives’]

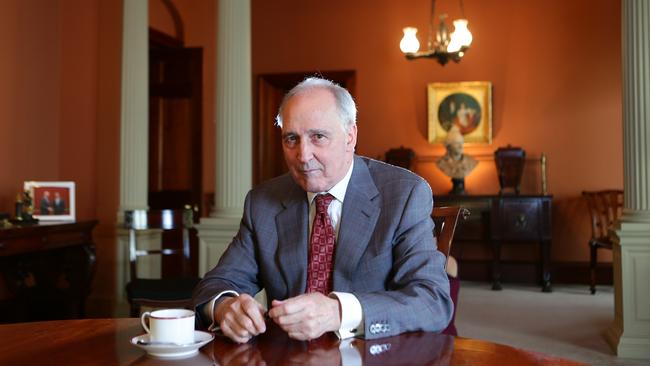

Paul Keating is seated on a chair in the middle of his office in Potts Point, Sydney. It is not just any chair. It is from the Palace of the Tuileries in Paris, in the period when Napoleon Bonaparte was First Consul of France. His arms rest on carved wooden griffons with lion heads and he relaxes into a soft cushion of horsehair. Keating purchased the chair last year, and had it crated and sent to Australia. (The French Government’s Mobilier National, attached to the Ministry of Culture, had an option to acquire the chair but didn’t exercise it). When I arrived at the office with photographer Nick Cubbin, the chair was already in place, isolated from everything else, set against a red-walled backdrop. It is a striking example of French neoclassicism, which draws on ancient Greek, Roman and Egyptian design, and expresses a philosophy of human progress with a moral and an aesthetic order, and the quest for innate beauty. Louis-André-Gabriel Bouchet painted a seven-year-old boy standing next to the chair that was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1810. That painting sold at Christie’s for $US181,250 in 2022.

“Art is not a peripheral thing; beauty is central to human uplift and achievement,” Keating later tells The Weekend Australian Magazine in an interview unlike any the former prime minister has done before. “The Directoire and to a greater extent the Consulat are the periods of consolidation of the French Revolution – the event that changed all civil life going forward. The lives we all lead today, our liberty and equality, come from that time, that moment. This has always anchored my interest in the period. Otherwise, you would have been subservient to some monarch ‘appointed by God’ and by a Church which serviced God by collaborating with the monarch. Had you been an ordinary person, your life would have been wickedly subordinate, the next thing to being a non-person.”

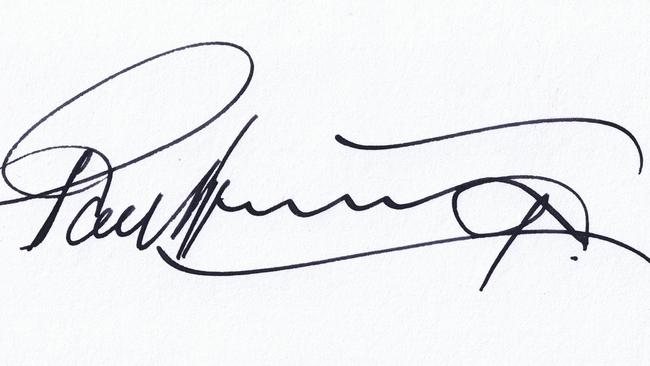

Keating has always had an eye and ear for the sensual grandeur to be found in music, objets d’art, painting, clothing, cars, architecture and decoration. These finer things have an inherent power that speak to his soul, fuel his passions and energise his still vigorously outspoken approach to politics and public policy. To the often dreary world of politics, he brought style and polish, and a touch of braggadocio, with his double-breasted Zegna suits, love of Gustav Mahler’s romantic compositions and Late Baroque-inspired signature with its swirling ornamentation made with a Montblanc fountain pen.

His world-renowned collection, focused on the avant-garde era of revolutionary France (1795-1804), is not merely an assemblage of “trinkets” but a manifestation of a philosophy. They illuminate his inner life.

“I’m definitely an aesthete,” Keating says. “That’s my whole thing. I’ve been an aesthete since I was a boy.” It shaped his conception of “big picture” style leadership and the attendant dreams of audacious statecraft. Leadership, he often says, is founded on imagination and must be matched with courage. “You must have the imagination,” he insists. “Imagination is everything.” To envision a better future, you need a nourishment of the mind. “Where does the spiritual uplift come from?” Keating asks. “Well, I think it comes from the inner life … you need the bubbling cauldron. Without the bubbling cauldron, you can never get the rise. Without the rise, you just do ordinary stuff. But then who wants to do ordinary stuff?”

To many, Keating was always a man of contradictions: the globe-shaping statesman and the take-no-prisoners political street-fighter. But they are not contradictory; they are inexorably linked. The task of the reformer is to combine imagination with indignation. It demands political battle. “What others would call the warrior statesman,” Keating explains. “Most of these people in history, whether it’s Alexander the Great or whoever were in the business of blood and gore, you know? And in politics, I was in the blood and gore business, fundamentally. But with big ideas always running it.” Winning debates in parliament, putting the blowtorch to opponents in interviews and slashing attacks on the campaign trail – it was about establishing political hegemony and policy authority. “Why do you throw Liberals around like rag dolls?” he asks. “Apart from the fun of it, the importance of it is for the betterment of the economy and society.”

To visit Keating’s office is to step into his sanctum. It gives full expression to his inner life that we discuss at length over four hours on a grey wintry day, as dark clouds gather in the distance and the conversation is punctuated by loud thunderclaps. His residence is what he describes as a “museum home”. To be welcomed here is an even rarer privilege as you navigate between an extraordinary array of antique furnishings, artworks and rare objects resting on pedestals, set within walls and backlit to perfection, over several floors. The office is where Keating works and sees visitors. Prime ministers, premiers, ministers, ambassadors, community and business leaders have all sat around the table to wrestle with issues, as a knight would in Camelot. It is made in tropical mahogany; a reproduction in the classic English Regency style from about 1805.

The office is located in the colonial-era sandstone building Tusculum, designed by John Verge and constructed in the 1830s. It shares its name, appropriately, with a ruined Roman city. After you climb the creaky wooden staircase and enter Keating’s office, you pass through two composite columns with volutes from the Ionic order that were once owned by James Christie from auction house Christie’s. The red walls are painted from fragments scratched off an Egyptian tomb preserved in a colour book that he purchased in London 40 years ago. At the far end are two large Egyptian statues with outstretched arms atop plinths. They were cast in bronze off the originals in black basalt at The Louvre a century ago. At the other end is an 18th-century terracotta bust by Jean-Jacques Caffieri. A classic French mantelpiece is installed in the middle of the room. The desk, lounge and chairs are stacked with books, clippings, correspondence and reports. Cabinets and tables jut out from the walls below paintings; they carry photos of family and friends alongside statues, clocks and candelabras. Keating’s extensive trove of papers is in the process of being transferred to the State Library of NSW. And the office itself, he hopes, will be preserved by the NSW Government and one day opened for visitors.

Anyone visiting the office cannot help but absorb the exquisiteness of these rare treasures. I first interviewed Keating at his office in 2010. In the years since, there have been hundreds of phone calls, emails and messages, more than 30 formal interviews and many casual discussions at Tusculum. We have eaten salads, quiche and salmon at lunchtime and drained glasses of wine in the afternoon light, while excavating memories from his past and analysing contemporary policy challenges, listening to sharp assessments of the political scene and hearing his tour d’horizon of international affairs. He pulls up things on his iPhone, escapes to a side room to retrieve a file or searches papers on his desk to illustrate an argument. He closes his eyes tight to retrieve a memory. He looks at you intently to share a killer fact. He gets animated when a person or policy offends. He makes notes to ensure you understand his full meaning, and phones after to check that you do. You depart equally energised and exhausted after a long session.

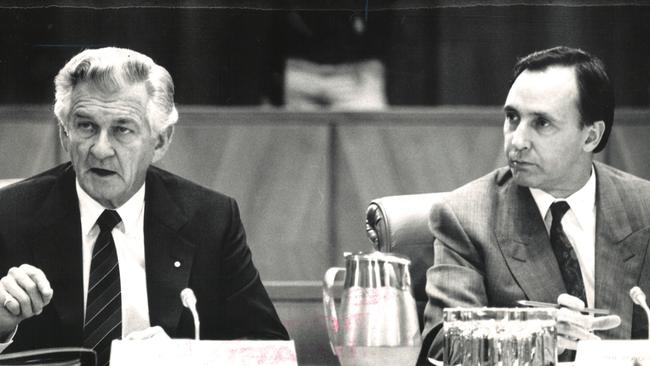

The former prime minister (1991-96) and treasurer (1983-91) left high school at 14, eschewed a university education and worked as a clerk in the public service, for a trading company and trade union. In 1969 he won the seat of Blaxland, a safe Labor stronghold in western Sydney, and was the youngest member of federal parliament that year at age 25. He became a minister in the final weeks of the Whitlam Government. As treasurer, he delivered significant post-war economic reforms that were the basis for three decades of prosperity. He had confidence and swagger, a vocabulary filled with wit and a tongue so sharp it was said it could clip a hedge. As prime minister, Keating won the “unwinnable” 1993 election and made native title and reconciliation, a republic, renewed engagement with the Asia-Pacific, superannuation and further economic reforms his focus. He gave speeches – such as the Redfern Park speech on reconciliation and the eulogy for the Unknown Soldier at the Australian War Memorial – that were praised for their oratorical impact. All of it informed, he insists, by the inner life. For Paul John Keating, now age 80, that journey of discovery began in wartime Bankstown.

It was a piece of classical music thatrang in Keating’s ear at age 12, and a gold pocket watch that caught his eye at age 15, that changed his life. In 1956, he and his friend Robert Campbell were riding their pushbikes when they stopped at Campbell’s home at Bass Hill. There, Keating heard a record playing on the veranda. It was Richard Addinsell’s piano composition Warsaw Concerto, composed for the film Dangerous Moonlight (1941). He asked Robert if his father would mind dropping the needle on it again.

Nearly 70 years later, Keating pulls up a clip of it being played on YouTube. “Dum-dum-dum,” he says, tapping his fingers. “Listen to this. Listen to this. Have you heard anything like it?” It still goes straight to his heart. Keating liked it so much that he went with his mum, Min, to the World Record Club at 177 Elizabeth Street, opposite Hyde Park, to purchase it. They found it on side B; Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 was on side A. He took it home and played it over and over. “Nothing was the same ever again,” Keating recalls.

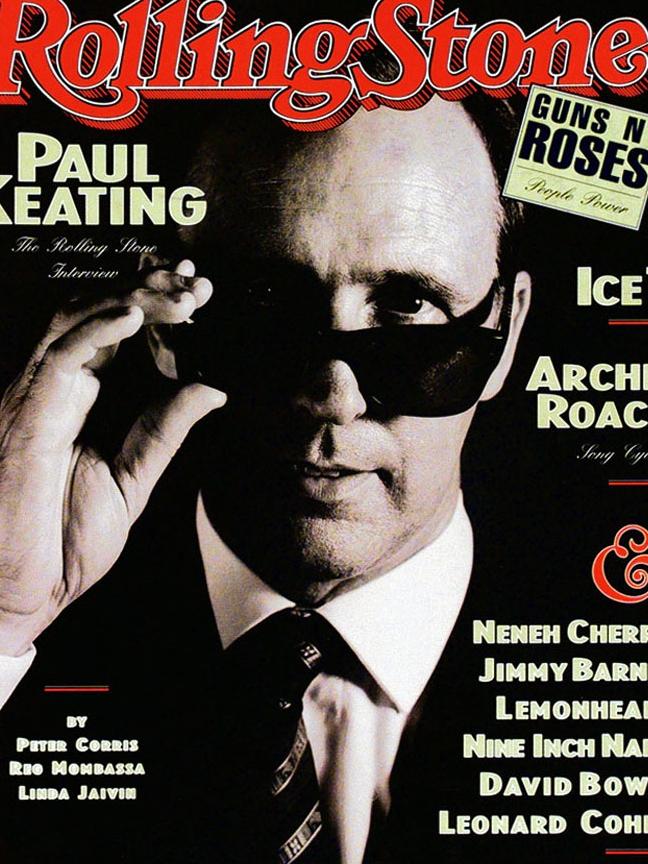

It set the pre-teen on a musical odyssey. Rachmaninoff led him to Borodin and Glazunov, and then to Beethoven, Bach, Brahms, Elgar, Tchaikovsky and Wagner. The compositions of the romantics especially appealed: Richard Strauss, Bruckner, Shostakovich and Mahler. After doing the rounds of local Labor Party branches trying to muster support for preselection, he would come home and put on Chopin’s Barcarolle. In the 1980s and ’90s, he would play these composers in the morning and evening, and on weekends he would invite cabinet colleagues and public servants to listen. “I reformed the Australian economy with my two best friends: Mr Mahler and Mr Bruckner,” Keating jokes. He also liked popular music: Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Frank Sinatra. He bought the records of Chuck Berry, Sam Cooke, Ben E. King, Otis Redding and Tom Jones. Keating’s favourite pop song is Midnight Train to Georgia by Gladys Knight & the Pips. In the mid-1960s he managed a rock and blues band, The Ramrods, and won them a recording contract with EMI. At the recording studio, he scoured the library for his records to take home. They were labelled “Factory Sample – Not for Sale”. Sixty years ago, he was invited to an EMI reception to meet The Beatles on their first Australian tour. He thought The Ramrods could make it big. But the band was never as committed. “I took them from nowhere to obscurity,” Keating says. A hint of that other life came in 1993, when he was photographed peering over Ray-Bans on the cover of Rolling Stone.

“Music speaks directly to your psyche,” Keating explains. “Music for the mind is like electricity for a motor. Once the current moves through the coil, the emotive power starts to move. Music is the highest form of the arts. All of a sudden, the mind is going and you let the composer take you to some place and then the ordinary things are just so easy to do. Rather than starting the day with a newspaper and a cabinet note from some department, you’re better off having the dreams, you’re better off having the fantasy, the power. And you can then just swallow the notes.” Beginning the day with music lifted him to a higher plane and he would arrive “high” at the office.

It is why he liked Keating! The Musical so much. It was written by Casey Bennetto and premiered in 2005 at the Melbourne International Comedy Festival. An extended Company B version, directed by Neil Armfield, was a smash hit, staged all over Australia. No other former prime minister has such enduring cultural power. Even now, almost 30 years since Keating exited parliament, Jonathan Biggins’ The Gospel According to Paul, his one-man satirical show, is drawing huge crowds.

In 1959, while working at the Sydney County Council, located in the Queen Victoria Building, Keating walked into Stanley Lipscombe’s antique shop across town. He spotted a gold fob watch made by Mignolet, a student of Abraham-Louis Breguet. He had to have it. It cost a few months’ salary so he put it on lay-by and paid it off over several months. The earliest newspaper profiles of Keating, from the time he was elected to parliament a decade later, record that he wore it with pride. “Only an aesthete would have bought that watch,” Keating says, smiling. Does he still have it? Keating pushes the chair out and goes to get it. He cradles it in his hand, marvelling at the how the student sought to emulate the artistry of one of the world’s greatest watchmakers, opening and closing it, and explaining its particular features.

“I started to look around at antique shops and then I found this watch which had a clarity and finality and a classicism about it which all the other watches never had,” he explains. “The person who made it was a student of Breguet, the greatest watchmaker in all history. And so, at 15 years of age, I hit upon a 1790s neoclassic model.” Why this particular watch from this period with these influences, I ask. “Well, I’ll never know,” Keating responds. “But it did influence my choice of things thereafter.”

A few years later, from about 1963, Keating would spend two lunchtimes each week talking to former NSW premier Jack Lang. Then in his eighties and nineties, Lang had an office on Nithsdale Street where he published the Century newspaper. He was not a typical mentor for a budding Labor politician – he’d been expelled from the party in 1943 – but Keating saw him as a time-tunnel to the past. Over a strict one-hour period, Lang would answer his prepared questions on a variety of topics and offer reminiscences of personalities and political events from before Federation and after. But most importantly, Lang taught Keating about the getting and using of power. With his mind energised by music and art, and Lang instructing him in politics, Keating saw no need for university.

“Fortuitously, I skipped a university education,” he says. “Largely because in the 1950s it was mostly not available. But intuitively I knew I needed a broad and generalised education for the kind of life I thought might lie ahead. I had more to learn than the discipline of a particular degree – I didn’t want to find myself locked into the corral of a profession, with the corral dominating my thinking or view of the world. Learning, after all, is borrowed knowledge. What I was looking for was intuition – an innate understanding of what could be fathomed yet some confidence about that which was otherwise unfathomable – the pathway along life’s tricky road.” Even after he arrived in parliament, he rejected suggestions from Gough Whitlam to earn a degree or follow the example of others such as Bill Hayden and undertake academic study at night.

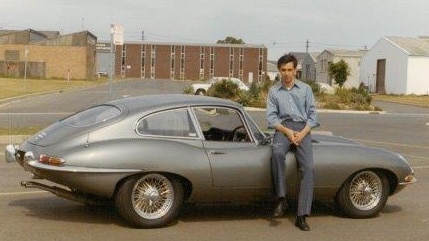

Not going to university, Keating argues, freed his mind. He sought intellectual nourishment by indulging personal interests. He owned a 1966 E-Type Jaguar, could disassemble and reassemble an engine, sail a small boat, earned a restricted pilot’s licence, studied the intricacies of cameras and film to photograph weddings, and bred budgerigars in his backyard. His main focus, though, was learning the art of politics. “Spontaneous authenticity is everything and this is more or less my credo,” Keating says, drawing on Goethe, who said it revealed your true virtues. “Leadership, if it is to amount for anything, devolves to imagination and courage. In public policy and leadership, there is a permanent case for audacity.” The means and ends of power need to be located and used. The task of a prime minister is to conceptualise a better future. They need both “the Himalayan view” and a “schematic” which serves as the blueprint for reform.

Keating describes the Menzian era, at its fag end when he entered parliament, as “the age of incrementalism” which inhibited Australia’s progress. “The public were fed such a meagre diet from Federation until, really, we decided to be an open country in the 1980s,” Keating argues. “I mean, we were a frightened little place until Bob [Hawke] and I showed up … the country never got a break.”

The most significant thing Keating says he did in public life was internationalising the economy. The most difficult was legislating the Native Title Act in response to the High Court’s Mabo judgment. “I put all the problems of the country on my own back to the extent I could solve them, you know, whether it be the financial markets or the product markets or, in the end, the labour market, or the big things like superannuation or native title or the republic,” he says. You need ambition, certainty and speed to get big changes: “You’ve got to want to burn up the roadway.”

Keating is a devotee of both neoclassism and romanticism. “The Enlightenment was about reason whereas romanticism is about the culture of feeling,” he says. “We want a facts-based world, and we want to respond to it, but want to do it with a heart. So, there’s a crossover between romanticism and neoclassicism – and I’m in the crossover.” They are two sides of the same coin. “Neoclassicism was of its essence a regenerative movement influenced by the exalted ideals of the French Revolution,” he explains. “It sought to slake decoration from all forms of art to create a style it believed to be eternally valid – valid as the impulses of the revolution were valid. Its power was its idea and the ideal of perfection: reflected in an austere representation of classicism, of the antique. But its searing ideals and authoritative presence were short-lived, though they provided the wallpaper to both the American and French Revolutions before yielding to a more emotional form of art, romanticism.”

Noting he is “fundamentally a romantic”, this led him to an exploration of romanticism in culture. Keating reveals that his favourite painter is J.M.W. Turner, in the English Romantic style, from the first half of the 1800s. He recalls going to the Tate in London in 1971 and seeing his landscapes and seascapes for the first time. “Nothing can prepare you for how great they are,” he exhales. With a dazzling use of light and colour, his impressionist style transformed painting. Paul Gauguin’s unique postimpressionist figurativeness, including his romantic vision of Tahiti, is another artist that captured Keating’s enduring interest. He regards Édouard Manet and Claude Monet, the impressionists, as doing something “pretty but not possessing the power” that Gauguin managed in his postimpressionist period.

“Romanticism, expressing an artist’s emotional ‘authenticity’, was seen as attributing validity to a work which mimetic art was incapable of doing,” Keating adds. “And the romantics at the time were out in force: Gericault, Delacroix, Goya, et cetera, later to be followed by Manet, then Monet, Pissarro. I always inhabited both camps, neoclassicism and romanticism. Neoclassicism with and for its Enlightenment ideals, its devotion to reason and perfectionism – much of which informed my calibrated approach to economic policy. [And] romanticism opened the yawning vistas of life replete with emotions that cram the human experience – which music goes out of its way to both join and to satisfy. I think I can claim, without refute, that you are much better with both. The culture of reason vying with the culture of feeling. Nevertheless, both share a common ideal: beauty. For as Stendhal said, ‘beauty is the promise of happiness’. I believe this to be true and have believed so always.”

This is the inner aesthete in the search for beauty. The quest for objets d’art that conveyed these ideals began with Louis XIV, the so-called Sun King with a refined taste and eye for the exquisite. “That period I’m interested in,” Keating explains. “That is Louis XIV, Louis XV, Louis XVI, The Directoire, The Consulat.” Although he has Napoleon’s silver coffee pot from St Helena, he says he is not really interested in the Empire period. “Empire was a martial style,” he notes. “People think I collect Bonaparte. I don’t collect Empire. After that, we go into second period Baroque, that is in Britain with Queen Victoria, and Charles X and Louis Philippe in France. It’s what I call Whorehouse Rococo or Bordello Baroque. I’m not interested in the middle junk of the 19th century.

“The next thing I like is Art Deco which has classic antecedents. French Light Deco from, say, 1920, through the war years and then into Art Moderne, particularly in France in the 1950s and ’60s. So, I’m as interested in those 20th century periods as I am the earlier 18th century.” This is Keating as tutor, explaining the intricacies of art and culture as he would the deregulation of the economy in the 1980s or shuttle diplomacy to establish the APEC leaders’ meeting in the 1990s.

I remember Anne Keating telling me that at about age 17, her brother bought a 19th-century marble bust of Beethoven and gave it to their mother. She proudly put it on display in the loungeroom of her Bankstown home. “There’s a sensuousness about sculpture, a completeness about it,” Keating explains. “It’s a most difficult art form, of course. I mean, to take a rock and make it human is pretty tough. After music and high literature, sculpture is next. I think painting follows sculpture in that order.” The one treasured possession that Keating could not part with is an 18th century sculpture of Truth with the sun on her chest, undressed from the superstitions of life by light and time. It is reminiscent of Bernini’s Truth Unveiled by Time on display the Borghese Gallery in Rome, Italy.

His favourite composer is, no surprise, Mahler. But Keating says it is a close competition with Bruckner. “Mahler knew he was the last great German symphonic composer,” he says. “Mahler wins by a good half head, but Bruckner is up there. Bruckner is the greatest symphonist after Beethoven. The piece of music which changed European music after Beethoven is the Symphonie Fantastique by Berlioz. If you’re thinking about, let’s say, Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler, Elgar, any of them, they all live a bit of Berlioz. Berlioz is still with them.” The records that he most searched for at the EMI library were recordings from the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Otto Klemperer.

Keating also wore style. “Menzies got around in a double-breasted suit,” he says. “I brought it back into fashion. I drove the local tailors here mad because I wore Italian double-breasted suits – Zegna. Neal Blewett used to say, ‘I always worried when you came into cabinet with a navy-blue suit and silver tie because if you were power dressing we were all going to suffer somewhere’.” Where did the power dressing come from? “I was always well dressed, that much my parents did,” he says. “I lifted it up to a sharper edge.” He would go to school with his shoes so polished he could see his reflection. When he started work at age 15, he dressed like the chairman of the board. Does style give authority? “I think so,” Keating responds. “The transmission of belief gives you authority [and] dressing for the occasion and being on top of it all is a visual manifestation of power and confidence.”

His signature is another indicator. “It is evidence of my lingering interest in the Rococo,” Keating laughs. Having seen it on archival documents stretching back to the 1960s and ’70s, it has remained largely consistent. “It’s a period after the Baroque of Louis XIV, before the coming of the neoclassicism of Louis the XVI,” he explains. “So, the Rococo is associated with Louis XV. It has a constant movement and swirling. So, if you look at my signature, it has a clear Rococo quality to it.”

At school in Bankstown, Keating dipped pens in inkwells as part of his learning, a habit he has maintained. It also enabled fast writing. “In a contestable cabinet, which I ran and Bob ran,” he adds, “ministers would say things and it would be good for you to be recording them as they say it because you generally had a reply.” Style and politics meet again.

In mid-1987, he took time out from talking J-curves and banana republics to give a 45-minute lecture to the National Gallery of Australia on painting, music, architecture, furniture and sculpture. It revealed another side to the reforming treasurer with cutting invective and graduate of Tammany Hall-style NSW Labor Right machine. He spoke of neoclassicism representing “a new order where reason and the common good triumphed over the old order”. He took along items from his collection, including a French-made bronzed candelabra (1795) and mahogany torchiers (1800). The audience was stunned. “I once came back from Paris with a little carriage clock by Breguet,” Keating recalls. “From that moment, I became a clock collector with the Canberra Press Gallery. It suited me to let them think that.” But his interests were evidently more expansive than clocks.

The journey to Keating’s inner life began by accident: hearing a record spinning at his friend’s house after a bike ride and spotting a watch in an antique shop while roaming the Sydney CBD. It led him to the intellectual and cultural ideas that underpinned the age of Enlightenment given voice by Rousseau and Voltaire on one continent and Franklin and Jefferson on another – at a time when, as he believes, the West had not yet “lost its moral mandate.” Keating explains: “It is bored with its own culture – it is culturally exhausted. Nihilism and an attendant loss of faith characterise modern life. There is no guiding light.”

For Keating, a generation ago, neoclassicism illuminated a framework to pilot his public and private lives – democracy and liberty from Greece, republicanism and the rule of law from Rome, and the arts and sciences of Egypt. The assemblage of “a philosophic collection” reflects this. “It is about finding an eternal aesthetic that never diminished with time,” he says. This was fundamental to the economic, social and foreign policy changes that he devoted his career to. But Keating says few, if any, politicians have private passions that drive their public lives. They are missing out, he insists. “What the inner life does is give you an inner purpose,” Keating says. “And you start to see things from a much higher altitude.”

Troy Bramston is the author of Paul Keating: The Big-Picture Leader (Scribe)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout