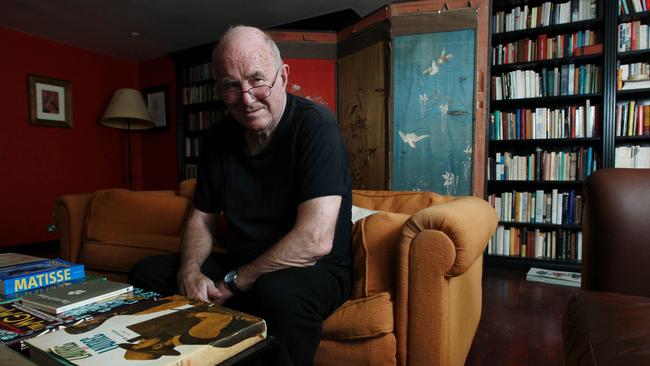

Conversations with Clive James: ‘He loved the written word, and told the young’

The Kogarah Kid was generous with his time and his suggestions for my Menzies biography.

A few months ago I re-watched Clive James’s 1991 documentary, Postcard from Sydney.

There he was, testing his athleticism against ironman Craig Riddington, describing the curious rituals of summer cricket sitting on The Hill at the Sydney Cricket Ground and walking around a derelict Luna Park lamenting that it might never be restored to its former glory as he braved the slide at Coney Island.

I enjoyed it so much that I corralled my family into watching it with me again, then sent an email to Clive telling him that it reminded me of being a wide-eyed 15-year-old watching it with my parents, pondering just who this extraordinary man was.

He appreciated the compliment but regretted the running side gag that Mozart also was born in Sydney. “It only caused confusion,” he said. “Moral: don’t strain to be cute.” Too cute? Here he was also riding a rollercoaster at Darling Harbour, arriving by speedboat at the Sydney Opera House wearing a tuxedo and enjoying a seafood lunch at Doyles at Watsons Bay.

Nobody compares to Clive James. He wore many hats — memoirist, essayist, poet, critic, novelist, lyricist, translator, television presenter, talk-show host, radio broadcaster — and had a career filled to the brim with bursts of creativity and originality. He could do almost anything. He managed to combine a cultured intellect with popular light entertainment.

Clive was generous to me. I interviewed him several times and we corresponded occasionally. I still find it difficult to believe this. I peppered him with questions about his life and work. He saw himself, first and foremost, as a writer who ploughed his trade in various fields. Even as he struggled — really struggled — through leukaemia and emphysema he still signed off emails with an upbeat, “Onward, Clive”.

As a teenager I read his Unreliable Memoirs. I picked up his volumes of essays and criticism, and dipped into his poetry. But it was his 1993 documentary and companion book, Fame in the 20th Century, that captivated me the most. Clive thought it was among the best things he did and was pained that the cost of the archival footage meant that it has never been repeated.

“As for my own management of fame, you could say I’m stunned to find that I’ve still got any, and will probably die from the sheer amazement,” he told me. “But I’d be mad to knock it, because it helps draw attention to my work: which is the only decent reason for seeking fame in the first place, and it’s dangerous even then.”

He thought the Unreliable Memoirs series was the best thing he had done in book form and was working on a sixth and final volume. An autobiographical anthology of poems, The Fire of Joy, will be published next year. He found poetry the hardest form of writing. “The real trick” with it, he said, was to “enjoy the drudgery” of it. He was immensely proud of many of his poems, including The Falcon Growing Old, Japanese Maple and The River in the Sky.

“I actually love teasing readers who think they know something about poetry but don’t; and even more I love flirting with readers who have a natural affinity for the stuff,” he explained.

“It’s in that second group — mainly women, strangely enough — that you also find the people who are most sensitive to a well-constructed prose argument.”

Although Clive was known for his wit, he acknowledged a sense of melancholy that pervaded his life. “I would probably have functioned better as a happy man, and certainly life would have been better for all those around me,” he told me. “The really tricky aspect was that I seemed happy. I had a dumb smile that created expectations.”

The biggest influence on his life was the death of his father, a prisoner of war, on his return home from World War II. “The loss of my father, and my witnessing of how my brave mother coped, these continue to be the great events of my life, right to the end,” he said. These thoughts weighed heavily in his final years. Last year, Clive sent me a “next-to-final draft” of his autobiographical book-length poem, The River in the Sky. I was in awe. It is a magnificent piece of writing. He was at the height of his talents as a writer as he neared the end, although he apologised for his long-expected death being so protracted. “It makes me look unusually active for a man on the verge of being officially dead,” he said.

I mustered the courage of a kid from Kogarah contemplating riding his billycart down a steep hill when I asked him if he would read my biography of Robert Menzies. He enthusiastically agreed. But he had one caveat: “The only question is whether I will survive to read it, but let’s try.” He began reading straight away and his compliments nearly gave me a heart attack. The next day, he wrote to say that he was “splashing about in the book while also carving through it in detail”. He made a few suggestions and apologised that he had to go into hospital but promised to read the full manuscript when he exited, and he did. I dragged the billycart up the hill for a second run, this time asking him if he would provide an endorsement. He did so without hesitation. I still cannot believe this.

Clive wanted to see Sydney again: the shimmering blue water, the enormous bridge spanning the harbour, and the sparkling tiles on the Sydney Opera House. He dreamed of another lunch of whiting fillets at Doyles washed down with a chilled bottle of Cloudy Bay. But he accepted that he would return only when his ashes were poured into the harbour.

Although an expat for decades, he still saw himself as a Sydneysider. “I can assure you that Clive in Cambridge is still the Kid from Kogarah,” he insisted. He was thrilled to have a plaque bearing his name on the Sydney Writers Walk at Circular Quay. He joked that Japanese visitors were startled to learn from tour guides that he was buried beneath it.

Clive thought his epitaph should read: “He loved the written word, and told the young.” I am testament to that. He recalled Raymond Chandler’s advice to writers about having discipline and focus, and not panicking if the words do not come. “If you can’t figure out these principles for yourself, you’ll never make it anyway,” he said. “And how bad would that be? There are far too many writers.”

When I asked what had given him the most pleasure in life — various genres of writing, presenting or interviewing — he said he loved it all but named another art form that I had neglected to mention: the tango.

“It took humility to learn it, and humility was something I didn’t have enough of, so I had to find some,” he said. “With poetry, incidentally, you don’t get a choice. I was told to write (The River in the Sky) by a shadowy figure with a gun in his hand, who turned out, upon close inspection, to be me.”