The hangover from Covid’s cheap and easy money exposes us to ruin

No one can predict what Washington’s Tariff Man will do, so we have to get our house in order to prosper in a dangerous new era.

Another by-product of the turmoil is the rise of protectionism, lately and wickedly, in Donald Trump’s helter-skelter revival of tariffs. While the US President’s targets have been better prepared, the safeguards and norms of the past are gone. Some fear today’s “economic wars” will become tomorrow’s shooting wars.

Governments and monetary officials have been muddling through this disrupted new era, exposed to public backlash from the cost-of-living crunch, financial market volatility and billowing deficits; they’re trying to normalise settings, while navigating the clean energy transition, messy geopolitics and societal ageing.

Federal parliament is back. Electioneering is at large: the Albanese government is offering more of the same, the opposition is piling on junk policy, and the spendthrift states are sinking to a painful day of reckoning.

Our nation kept its head in the eye of the Covid storm, but has lost its way in the aftermath. If you forgive the fiscal excesses and discount the anguish and decay from lockdowns, our “administrative state” performed well during the pandemic.

In Australia’s Pandemic Exceptionalism (UNSW Press), economists Steven Hamilton and Richard Holden laud the $300bn-plus fiscal hit amid immense uncertainty; it was imperfect but effective stimulus, notwithstanding the great inflation that followed. But vaccine procurement design, penny wise and pound-foolish as they say, was among the “very worst” in the world and a public policy catastrophe; it delayed reopening by months, precipitated avoidable and costly lockdowns, and led to deaths.

So-called “excess mortality”, deaths above what could be expected, peaked at 20,000 in 2022 (or 11.7 per cent above trend), mainly due to the spread of the virus in the community. Since Covid-19 became endemic in that year, authorities believe it has accounted for two-thirds of excess deaths, with almost half of them among those aged 85 and over.

The Economist has estimated that since the start of the pandemic (to last June), Australia had 163 excess deaths per 100,000 people, which is higher than New Zealand (19), lower than the US (434), UK (409) and Canada (225).

“In the final accounting, there’s no doubt our policy successes outweighed our policy failures,” Hamilton and Holden write in their book. “Overall, Australia’s handling of the pandemic was exceptionally good.”

Yet the pandemic’s long tail now demands policy nimbleness to get our house in order; to clear red tape, trim the budget flab and taxes, so that we are competitive, not just on cost, while diversifying our offering to the world. We need investment and the private sector to drive growth. But we’re in a funk, “a sad economy without much hope” as one economist put it with a jolt recently.

As the druids of central banking have decreed, nations need to boost the supply side of their economies to deliver higher rates of growth. “Ultimately, a broad change of mindset is called for to dispel a deeply rooted ‘growth illusion’ – a de facto excessive reliance on monetary and fiscal policy to drive growth,” the Bank for International Settlements said in its annual report last year.

Australia, too, has been caught in this trap of cheap and easy money, plus people power, to pump-prime recovery.

There was a migrant outflow during the pandemic; when the border was reopened between late 2021 and early 2022, students, workers and backpackers flooded back. Businesses needed staff, universities and colleges wanted in-country customers.

According to the Department of Home Affairs, there were 1.6 million temporary visa holders with work rights here at the start of 2022. Last month, there were 2.2 million foreigners across these employment-eligible categories; the rise is due in equal parts to students and graduates on one side and working holiday-makers and foreign workers on the other.

Add in permanent migration of 530,000 over the past three financial years and it’s clear the boom driven by young foreigners has pumped up the size of the economy – more supply and more demand. Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock has said the population shock is, on balance, “a wash” for inflation (and therefore interest rates), notwithstanding the strain on housing, transport and social services from a surge that caught planners off guard.

Officials now complain foreigners “just won’t go home”. Administrative appeals have spiralled after a crackdown by the federal government on education providers and sham students.

The number of people on bridging visas, awaiting a decision to work or study here, has doubled in the past 18 months to 343,000 (the same number that greeted Labor in 2022 as it began clearing the backlog from the Coalition’s go-slow). While the federal government has tightened up migration policy to bring down the numbers from the record inflow, it’s also been ad hoc and panicky, rather than sensible and strategic.

On the consumer front, central banks missed the post-crisis inflation surge; we were six months behind our peers in lifting interest rates, which were near-zero. To preserve job gains, the RBA did not hike its policy rate as much and so is behind its counterparts in easing monetary restrictions.

One reason, plainly, behind the RBA’s concern that inflation may not return to target sustainably has been the strength of public spending in keeping the level of demand above supply. BIS general manager Agustin Carstens said this week that bringing inflation to heel “does not rest solely in the hands” of monetary officials.

“For central banks to achieve low inflation and financial stability, it is essential that fiscal policy ensures public debt sustainability,” he told a gathering in St Louis. “The sharp increase in public debt levels in recent years, coupled with large and persistent fiscal deficits in many jurisdictions, poses significant concerns.”

Canberra has not helped the RBA, with Jim Chalmers directing borrowed money into a bloodless economy that can’t absorb new dollars; this is diabolic, proof the private sector is being starved of fresh capital and labour, in contrast to the flush public sector.

The big business lobby has put forward a “big five” election platform: easing the cost of living by capping budget spending growth and lifting productivity by simplifying the tax system; more housing supply; a nonpartisan net-zero road map; a skilled workforce; and better health and care services

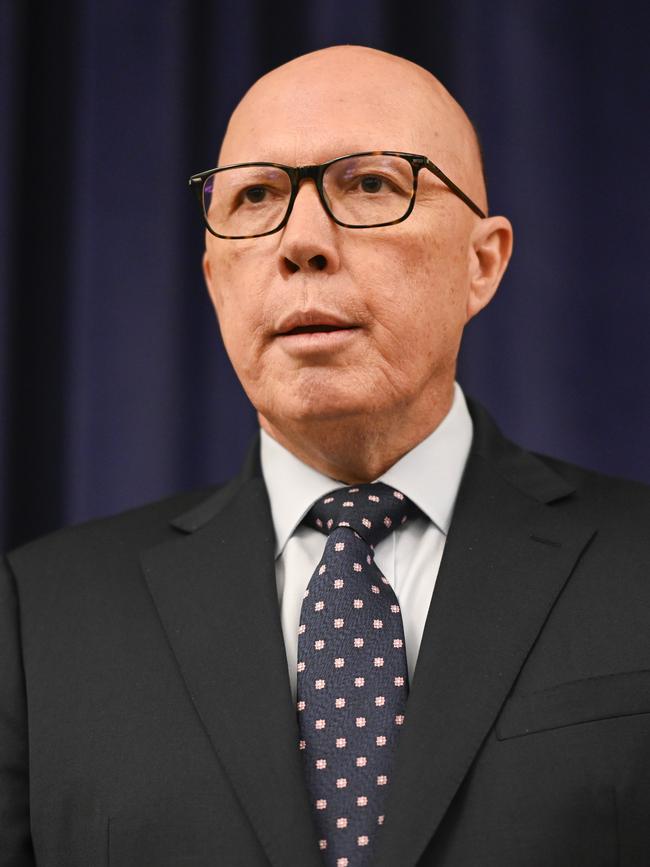

Where is the party of free enterprise on spending less and taxing better? Peter Dutton’s pitch is “vote for us and we’ll tell you all about it when we win government”. Federal spending will come under control, supposedly, because Dutton has promoted an expert in the art of No.

There is not a lot of corporate huzzah for the Coalition’s nukes fantasy, supermarket divestment or slashing permanent migration. It’s puzzling that there is some big brother love from the Business Council on the “free lunch for bosses” tax rort, a standout in a pageant of ugly populist policy.

Still, let’s not let an inveterate spender like Buzz Chalmers off the hook; it’s deficits to infinity and beyond, and new adventures in off-budget galaxies. Interest payments are rising, as the average weighted cost of borrowing across the yield curve has increased, reflecting global markets. And yet, net debt at one-fifth of the economy is back to where it was before the pandemic.

But the fiscal impulse is greatest in the provinces. S & P Global Ratings this week said states and territories were spending at above Covid’s emergency levels. S & P analyst Anthony Walker argues “the pandemic is over, but pandemic-size budgets aren’t”.

“Spending soared at the onset of the pandemic when interest rates fell to record lows, and states chose to support their economies and households to avoid large and prolonged recessions. That was 2020, this is 2025,” he said.

Deficits have soared; the problem is spending, not revenue. The cost of running Queensland has increased by 50 per cent since 2019. Victoria’s debt has tripled. At the start of the decade, capital works across the states were expected to peak at $64bn in 2020; it’s now forecast to breach $100bn in this financial year and next.

Fiscal discipline is out, harming the global reputation of the states, and it’s likely to cost taxpayers more in the end. This slippage keeps interest rates higher for longer, and there are fears nations will become more inflation-prone amid a time of rising debt, population ageing, trade wars and decarbonisation.

This is not a time for mulish mediocrity, a lurch towards cargo cults and casino capitalism, simply waiting for something from the heavens to lift our living standards and repair our public finances.

Washington’s Tariff Man is setting a cracking pace, while our leaders are proving to be slower, clueless and timid. In our illusion of control, as prosperous people with time and treasure on our side, we are exposed to a world of threats. Australia is stumbling and the shadows are lengthening.

Covid is the curse that keeps on keeping on. It’s been five years since the coronavirus busted out of Wuhan and up-ended our lives. We’re still ailing under its dark shadow of high inflation, a population boom, battered institutions, bigger government, and elevated borrowing costs.