The golden age for Jews is over

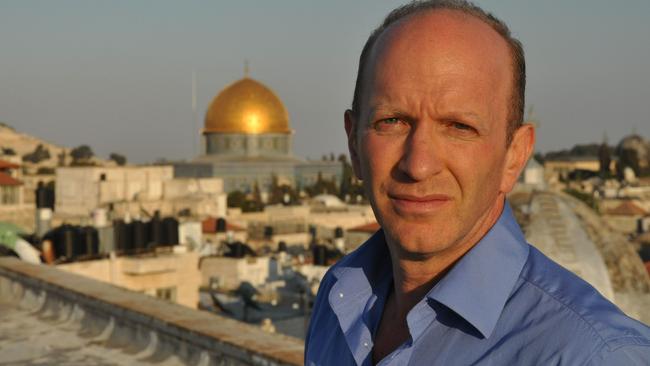

What caused the West’s decline, and where do we go from here? We put these questions to British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore.

Did you know that Joseph Stalin could sing with perfect pitch? Or that he was so scared of his wife that he would hide from her in the bathroom? Did you know that Peter the Great liked to surround himself with naked dwarfs? Did you know Catherine the Great – long smeared as a nymphomaniac – was actually a lovelorn monogamist? Or that King Herod’s genitals once exploded with maggots?

Most historians bore you with dry accounts of battles and treaties, and it’s hard to remember any of it. But not Simon Sebag Montefiore, who writes 900 pages that you cannot put down.

Sebag Montefiore is one of the most important historians alive today. His many books – including Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar, The Romanovs, and Catherine the Great & Potemkin – are essential to understanding power, politics, revolution, dictatorships and, above all, human nature.

While most of Sebag Montefiore’s books are biographies of people, Jerusalem is a biography of a city – one that is “the house of the one God, the capital of two peoples, the temple of three religions, and she is the only city to exist twice – in heaven and on earth”.

The book takes you through 3000 years of Jerusalem’s history, from King David to Benjamin “Bibi” Netanyahu. It is a must-read. It has sold more than a million copies, and it has just been reissued in paperback.

With the ceasefire deal under way in Israel and with Donald Trump a few weeks into his second presidency, we could not think of a better person to hear from at this moment.

On the crisis of confidence in the West

Bari Weiss: A lot of us grew up under the belief that history had ended, that liberalism and capitalism were obviously better than any other system and would conquer the world. That now seems so naive. How did we get that so wrong?

Simon Sebag Montefiore: I think what we’re coming out of is an extraordinary period. We’re coming out of what I would call the 75-year peace. But in 1945, when Nazi Germany was vanquished, there was such a shock that all sorts of things became clear. All sorts of taboos were established – anti-Semitism, for example. But it also became self-evident that Western liberal democracy was the freest, the most open society in which to live, and the values that engendered brought us great advances in world affairs: the rules-based world order, supranational organisation, the United Nations, the idea of world human rights. And then in the 1960s, what I call the “Great Liberal Reformation” of gay rights, abortion, the pill, all these sorts of things. None of that was challenged by anyone for a very long time. So America could go about its mission of selling those ideas to the world.

And then, of course, the Soviet Union fell. But it’s interesting to realise that there’s never been a period like this in world history. This wasn’t normal. Normally, everybody is against everybody. Most world history is about a multiplayer game, but the Cold War was a game of chess between two great players: the Soviet Union and the US. And when that ended, America lost its way.

America was the unique power. And for whatever reasons – some of them understandable, some of them preposterous – America squandered that moment, partly with the disaster of the Iraq War. And out of that has come a reordering, a return to normalcy in which it’s ever more important that our societies, especially liberal democracies, keep that solidarity, that coherence. And it’s at this very moment that we’re actually eating ourselves in an act of self-mutilation. This is a challenge from within society itself.

One of my great heroes, the 14th-century Arab historian Ibn Khaldun, said states don’t fall because of military defeats. They usually fall because of psychology. And that’s worth thinking about.

BW:If you had to diagnose the psychology of America and the West right now, what would you say?

SSM: A crisis of self-confidence. A crisis in which people have forgotten that the freedoms and values they hold were fought for. If you look at our nation, we kind of generally agree that nation states are the best way to organise. Empires aren’t a good thing. And when I think about the young people who went off to fight for democracies in World War II, for example, how many of the present young generation would fight for our nation now? And yet our nations can represent the highest ideals and values. I’m kind of old-fashioned, but I believe that America represents the highest values of freedom. I believe in that stuff.

On the end of the golden age for Jews

BW:Since October 7, there is a feeling among the diasporic Jewish community that the old world is shattered. And people have been talking about how they felt like they were on a holiday from history, and that is over. I want to ask you about that phenomenon. Has there ever been a people that had the luxury of being on a holiday from history?

SSM: It’s an extraordinary thing. The term golden age has been used a lot in the past couple of days, but most of us here grew up in the golden age of the Jewish nation, of the Jewish people. And yes, we didn’t realise how fortunate we were, though our parents told us, but we didn’t really believe them. And I guess one would date it from 1947 to October 7, 2023 – that was the golden age of Jewish people. It was unique, just as the peace we’ve known in the rules-based international order is absolutely unique in world history.

BW: Was there anything that we could have done differently to keep the golden age going? Where did we go wrong?

SSM: The big mistake was – and this isn’t just a Jewish thing – this is about liberals in the widest sense of the word, in the sense of democratic liberals.

BW: You don’t mean liberals in a partisan sense?

SSM: I mean it in the widest sense of the word. I think people have been far too accepting of views that they knew were unacceptable in all schools, but even more so in the academy.

BW: Like the idea that America is bad or evil, or not the greatest? I heard that language every single day that I was in college. And no one challenged it.

SSM: Exactly. It’s a big thing. It’s like the idea that you can reverse history, go back in history and then adjudicate it. Who was right and who was wrong? That particular ideology has taken over much of university life, and we didn’t really notice it. We were sort of all taught it, but we didn’t really take it seriously, and we didn’t realise that it could have real-life effects.

To call October 7 a wake-up call is an understatement. People who we trusted – professors, journalists, charity workers – suddenly started celebrating the killing of civilians, the murder of grandmothers, the rape of girls, and the stealing of people as an act of war. And that was a terrible moment. I think we all went through it, and it was astonishing. That day, I remember watching professors who were at Harvard and Yale and Princeton suddenly saying ‘This is just a wonderful act of resistance’. And that was terrifying, wasn’t it?

On how Jews lowered their guard:

SSM: Language is hugely important. We have this sort of strange phenomenon where everybody says they’re anti-racist but hates Israel. This sort of homogenisation and romanticisation and universalisation of the Holocaust as a tragedy of history. We wanted to include other people in this story.

BW: Why did we want to do that?

SSM: America is the centre of the world and the centre of world culture. The experience of the Jews in America is unique. I think American Jews started off as an immigrant population like others, and then became one of the ruling establishments in the American republic. And I think the Jews found this extremely uncomfortable, because Jews are liberal leaning.

A wonderful thing about Jewish people is they think about other people. But the problem is they thought too much. And that has led to too many Jews lowering their guard. I think that has been a tragedy and it leads us back in full circle to what happened in academia, that we lost control of values in academia, and we surrendered academia to an ideology that we felt was virtuous, we hoped was virtuous.

I also think this isn’t just about Jews. This is also about politicians in America and public-service workers in America and charity workers and people who cared about democracy in America. They literally took their eye off the ball and thought, OK, this is good. It sounds kind of good. This sounds kind of virtuous. It’s anti-racist. It’s against anti-Semitism. And there are dark things in all of our histories. And by the way, there’s no problem, as a historian, with writing about the dark things in American history and British history and imperial history and in Israeli history. There’s nothing wrong with writing about this stuff. It doesn’t mean that we have to turn our society around into a sort of witch hunt and to pursue and to simplify everyday life into a battle of goodies and baddies.

On being a Jew today

BW: I guess the question I’ve been thinking about a lot personally is just how do we learn to be Jews inside history? I don’t feel that my generation was necessarily given the tools, and we’re now having to feel our way towards them. And I would love for you to reflect just a little bit: How do we be Jews in this historical moment?

SSM: I hate to say this because it’s an agonising thing that we are sitting here in 2025, but we must regain our instinct for danger, which we’ve lost in the last 70 years, because we’ve been living in the golden age of Jewry. And it doesn’t mean that we’re all going to be in danger all the time, and we have to cry “anti-Semitism” every second. But we just have to regain the instincts, the sensitivities, that our ancestors had.

My parents, when they were growing up, were real quiet. My mother was always saying to me, “Give an extra tip, because they know we’re Jewish.” But at the same time, she was so grateful to Britain, because Britain had given them safety, and Britain still gives them safety. America still gives American Jews safety. But I just think it’s a time for a little more awareness about who we are and how others see us.

This isn’t a moment of despair, but more of what history teaches, which is just realism and self-awareness and the realisation that the honeymoon is over. And the one thing we must not do as Jews is bend ourselves, distort ourselves, convulse ourselves, and mask ourselves to suit the wishes and demands of our enemies. That is the biggest mistake.

This is a transcript of Bari Weiss’s interview with author Simon Sebag Montefiore. The podcast and transcript were originally published on The Free Press website.