George HW Bush diary reveals his love of Australia on birth centennial

Diary entries, never published before, reveal George HW Bush’s regard for Australia.

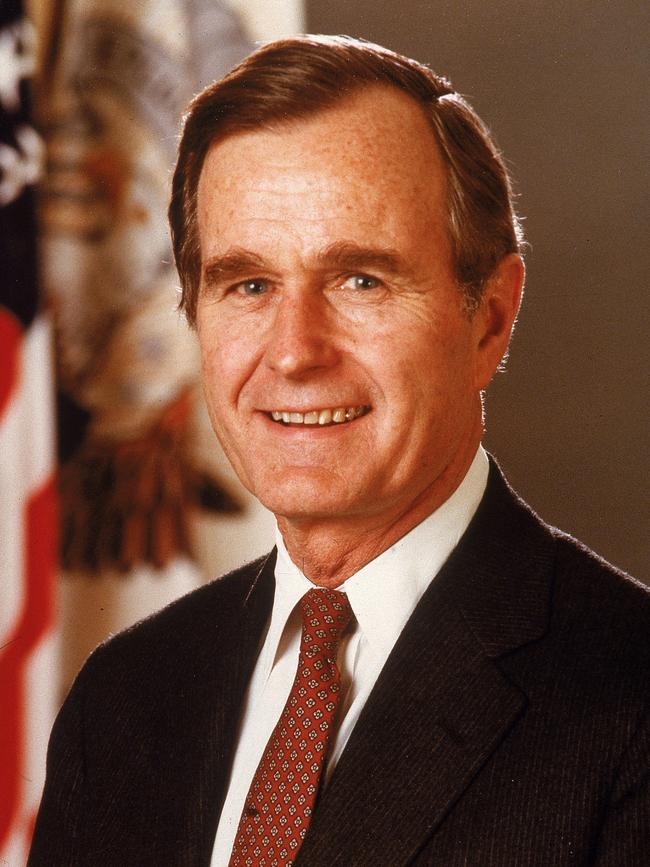

Bush had a unique relationship with Australia. He was the first president to visit since Lyndon B. Johnson in December 1967. He established warm relationships with Bob Hawke and Paul Keating The latter hosted Bush from December 31, 1991, to January 3, 1992, and later as a private citizen in November 1994 and provided Kirribilli House for him to stay.

I had the opportunity to interview Bush in May 2018 – one of his last interviews – and long extracts from his unpublished personal diary were provided to me in July 2021 by the George & Barbara Bush Foundation and George HW Bush Presidential Library and Museum for my biography of Hawke. Never before revealed diary entries are disclosed here in Inquirer for the first time.

In January 1989, Bush was a new president at a hinge point in history as the Cold War was ending. During his term, the Berlin Wall fell, the Soviet Union collapsed and he led an international coalition to liberate Kuwait from an Iraqi invasion. Russia experimented with democracy, East and West Germany unified within NATO, and arms reduction treaties were signed.

Bush signed into law the Clean Air Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1991 on employment and the Americans with Disabilities Act. He negotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement. And he promoted community service and volunteering with his Points of Light program. It was the sluggish economy and a broken promise on taxes that ultimately cut his presidency short after one term.

“The bilateral relationship between allies as historically close as the US and Australia has always been a priority,” Bush told me. “Because of the many things we shared – basic values such as our commitment to democracy, freedom and human rights – I do not recall any major fires that needed to be put out. I hope it is not revisionism to suggest our consultations always seemed to be working more on refinements to an already extraordinarily good and productive partnership.”

In his diary, Bush wrote that he had “a special relationship” with Hawke. They met several times and talked regularly on the phone – more than any other president and prime minister. Diary and phone transcripts document extensive contact. Hawke was an eager and early ally on Kuwait and they traded information about changes under way in China and the Soviet Union. It was because of his relationship with Hawke that Bush visited Australia.

“The warmth of the greeting from the Australian people was everywhere,” Bush recalled in his diary after arriving in Sydney at 8pm on New Year’s Eve 1991. “Workers coming out of the factories – young and old – and the old were particularly emotional about it and, I must say, I was emotional about it when I went to the (Australian) War Memorial in Canberra and saw the names of all the fallen soldiers.”

The president was immediately struck by the welcome. “The people are so damn friendly,” he thought. “I kept thinking to myself, ‘Gosh, it’d be fun to come back here someday and visit some of these wonderful people, go fishing, and just have a relaxed time seeing that beautiful country.’ ”

But he regarded the local media as “damn rude” and was irritated by them. “One smart-Alec reporter from the television in Canberra who made some comment that went something like this, ‘Well, now that you’ve discovered a road map and found your way here after 25 years, I’d like to ask this question,’ ” Bush recalled. “I wish I was quicker and could come up with some real put-down, like telling him that rudeness didn’t get him anywhere.”

The president had a busy schedule in Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra with speeches, meetings and informal gatherings. He also addressed the federal cabinet. His diary chronicled the visit and channelled frustrations. He railed against “ugly and nasty” Croatian protesters and “crazy women’s groups”. He fretted about putting on weight and how exhausting overseas trips could be at age 67. “We go from one event to the other, just pounding away – event, event, event – and I got deadly tired,” he recorded. “I just hate taking these sleeping pills.”

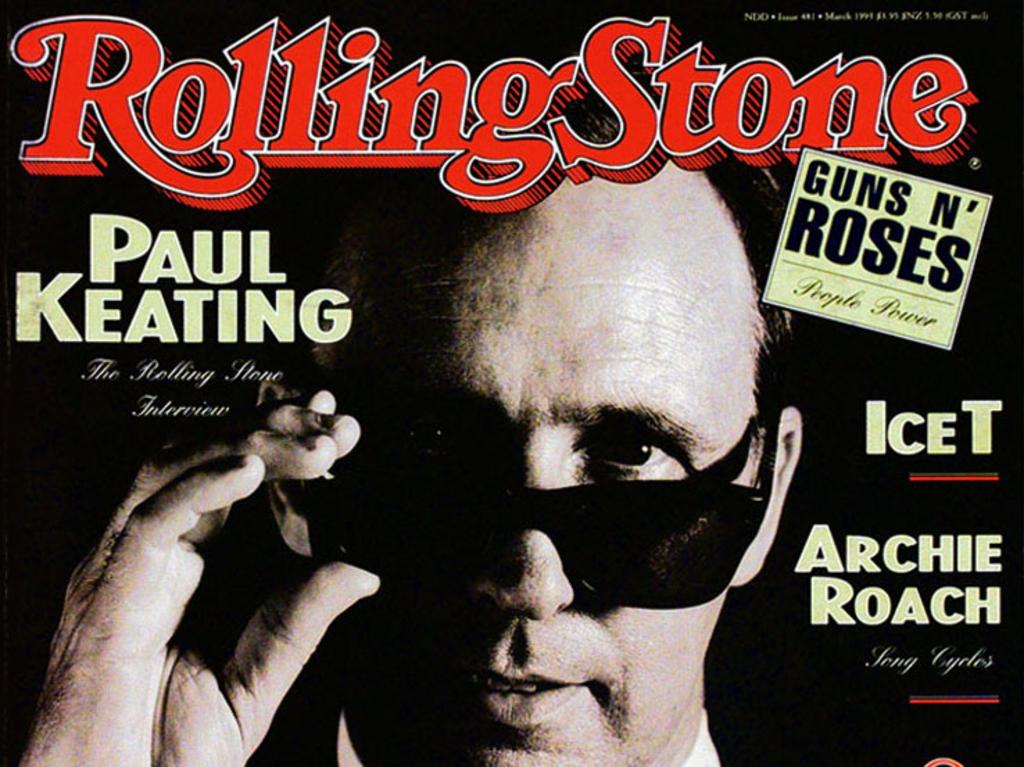

It was a time of political change in Australia. Less than two weeks earlier, Hawke had been defeated by Keating in a partyroom leadership ballot. Keating – who met Bush in 1971 when UN ambassador and several times in the 1980s as vice-president – was now prime minister. Bush was made aware that not all Australians approved of the change.

“When I went running in Sydney,” the president diarised, “I got out of the car to shake hands and a man came up to me and said, ‘Keating is not the man. He does not represent us.’ I thought he said, ‘He’s not God-fearing like you are,’ but in any event, he made clear to me that Keating was unpopular. I asked the guard and he said, ‘Yes, there was a lot of talk like that in Australia.’ ”

But Bush liked Keating immediately. The feeling was mutual. Keating met Bush at Sydney airport and they watched the end-of-year fireworks from Admiralty House. They met formally the next morning at Kirribilli House. Photographs taken by the White House photographer show the prime minister meeting the president at his car, showing him sites on Sydney Harbour and chatting amiably in the drawing room.

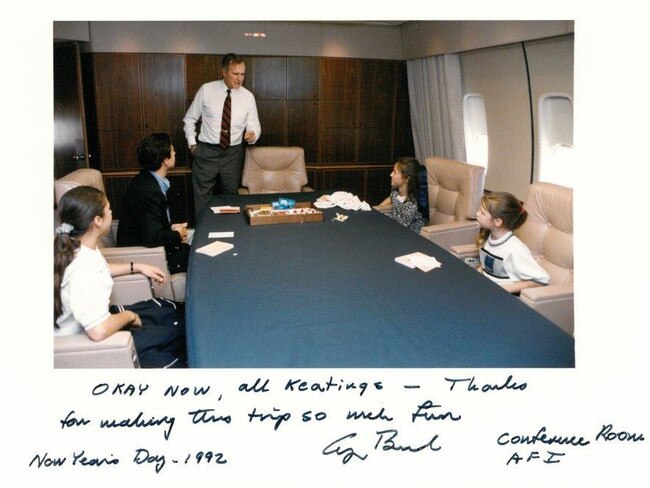

“Paul Keating (had) just thrown out Bob Hawke and he seemed a little conscious of the change,” Bush recorded. “That’s the only way I know how to describe it. I tried to put him at ease by inviting his children to fly down with us from Sydney to Melbourne and I think that proved to be a very good move.

“The kids were delightful – the three girls and the older boy – and they just couldn’t have had a better time on Air Force One and the Keatings (Paul and Annita) were there to meet them when we arrived in the nation’s capital and one of the girls gave me a big hug.”

At Kirribilli House, Keating seized the opportunity to lay out a new vision for the US and Australia in the Asia-Pacific. He proposed elevating the APEC trade forum of ministers into a leadership meeting. (In mid-2016, Keating provided me with his handwritten notes from the meeting and the formal record of dialogue taken by his foreign policy adviser, Ashton Calvert. National security adviser Brent Scowcroft also made a note, which I now have unredacted.)

“There (is) a need to develop stronger economic institutions in the Asia-Pacific,” Keating told Bush. “APEC (is) the natural forum in this regard.” Bush was interested. Keating came to his proposal: “It (is) worth considering holding occasional meetings at the head-of-government level.” Bush gave Keating the go-ahead to advocate the idea to other regional leaders.

Trade was a focus of Bush’s meetings. “We spoke of trade, the openness of the trading system, the importance of our relationship with Australia, not taking friends for granted,” Bush diarised. Keating’s grand APEC vision would be realised during Bill Clinton’s presidency. At the time, Bush was hopeful of a “successful conclusion” to the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade negotiations under way.

“Paul Keating conducted himself well with me,” Bush said. “The one contentious item really surfaced is the farmers. They’re hurting. Our EEP (Export Enhancement Program) program, they claim, is driving them to their knees. It really isn’t. It’s mainly Europe and our farmers are hurting. I made clear to them we were not going to give up the EEP program and this didn’t enrage the farmers – ’cause they didn’t expect that – but they picketed. I felt badly.”

On January 2, Bush addressed parliament. He referred to Keating’s idea of using existing institutions to “expand and liberalise trade” in the region. Hawke sat on the backbench. After the speech, Bush gave Hawke a wave and got emotional. The president and the former prime minister met at the US embassy later that day.

“When I got up to give my speech in Canberra to the parliament, something that they made clear to me had not been done by anyone else in the new parliament building … I looked over and I saw Bob Hawke and I choked up,” Bush said. “He looked smaller and it was because of him that we undertook the visit in the first place and he looked a little bit saddened by alla’ this change, but later he came over to the house and I gave him a big abrazo (Spanish for embrace).”

A reception was held in the Great Hall. Bush thought the music and singing was “marvellous” and noted the compliments on his speech, which had been mostly “ad libbed”. As Bush mingled with politicians, he did not hit it off with opposition leader John Hewson even though it was “widely predicted” the Hewson would soon be prime minister.

“(Hewson) gave a, unfortunately, politically over-toned speech,” Bush noted. “He took a slight swipe at Keating and how he’d gotten rid of Hawke – (a) passing blow that he’d tried to do humorously – then he got into lecturing me a little bit on the agriculture program which we didn’t feel was necessary.”

As Bush left for Singapore, he reflected positively on the visit and disclosed that Keating secretly hoped he would beat the yet-to-be-chosen Democratic candidate for president in November. But the coming election was something Bush loathed.

“They were very nice about me and world leadership and all that kind of thing – very nice indeed – and Keating told me as I left of his keen interest and commitment to seeing me re-elected.” He added that Australians “talked of us as the undisputed leader of the free world and praised my own position, which was pretty reassuring. I hope it plays in the US.

“This concept of separating domestic from foreign policy is an impossible one. The Democrats are appealing to the lowest common denominator and so is (Republican) Pat Buchanan but, for some reason, I have a rather comfortable feeling that I can handle it next year. Although, I dread it. I really dread the politics and the ugliness of it all.”

Bush lost the election to Clinton but they later became good friends. Bush was a man of character. He had integrity and humility. He devoted his life to public service, as a young naval pilot in World War II all the way to the presidency. And he was a good friend to Australia.

George HW Bush, 41st president of the US, was born 100 years ago on June 12, 1924. The centenary being celebrated across the US coincides with a continuing reassessment of his four-year presidency and long career of public service that also included vice-president, CIA director, China envoy, UN ambassador and congressman.