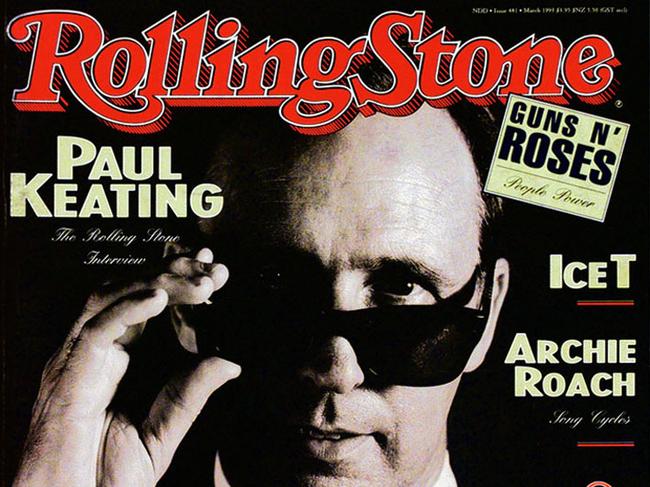

Labor’s leading man lays out the big picture

In a no-holds-barred interview, Paul Keating has savaged Scott Morrison for wilfully surrendering our sovereignty and lashed Anthony Albanese for his complicity.

When Paul Keating wrested the prime ministership from Bob Hawke 30 years ago, he came to the nation’s top job with an audacious philosophy of political leadership and an ambitious agenda to turn Australia in a new direction.

He viewed the prime ministership as an agency for action, saw leadership as the combination of courage and imagination, and understood how to gain and use power. He dreamed big dreams, challenged Australians to reconsider their country’s past and future, and coupled elevated oratory with slashing attacks on his opponents to achieve his aims.

In his only interview to mark three decades since he became Australia’s 24th prime minister, sworn in on December 20, 1991, Keating discusses leadership, “the big picture” and contemporary policy issues. At age 77, he remains visionary, unbowed and, as ever, indignant.

“I saw the prime ministership as a chance to move away from the economic reconstruction of Australia to Australia’s geo-strategic repositioning in the region,” Keating tells Inquirer. “I had thought about these issues all my political life. When I became prime minister, I knew exactly what I was doing, what I wanted to do and how to achieve it.”

On December 19, 1991, Keating defeated Hawke in a Labor leadership ballot by 56 votes to 51. The great political duo had terminated six months earlier, when Keating first challenged Hawke after reneging on a secret agreement to hand over the leadership made at Kirribilli House in 1988.

He had long coveted the prime ministership – not to preside but to lead. His two decades in parliament had been a study in power. Now, having seized it, he reshaped the government. Hawke’s profound belief in consensus politics gave way to Keating’s crazy-brave, thrilling, highwire conviction politics.

“While the modalities of the process of government between the Hawke government and mine were pretty much the same, I knew any government that I would lead would have a wholly different set of objectives,” Keating explains.

“We had to have a new approach to leadership, one where there was a political premium for good policy and one which was able to convince the public that good policy brought its own reward. If you look at my approach to public life, it has always been about instructing the public – about educating them to the problems; to bring them with me.”

He communicated bold ideas with intensity and passion. He viewed parliament like a gladiator viewed the coliseum: blood sport. His verbal assaults were legendary. But so was his oratory, such as that honouring the unknown Australian soldier in 1993. That speech is engraved on the Australian War Memorial.

Although recognised as the architect of Australia’s modern economy as treasurer (1983-91), Keating’s achievements as prime minister have often been overlooked. His “big picture” framework encompassed economic, social and foreign policy between 1991 and 1996.

“The big picture is shorthand for talking about the large geo-strategic and geo-economic forces,” Keating explains. “Those forces are now virulent and therefore command the thinking of a national government about how one pilots a society through and in the face of those forces. The big picture does change nations but there are relatively few artisans in the craft of nation building.”

First, was reckoning with Australia’s past. He gave the original apology to Aboriginal Australians in the landmark Redfern address in 1992. This was followed by the legislative response to the High Court’s Mabo judgment with the Native Title Act in 1993.

Second, he put the republic on the agenda and won majority support for it in the polls. In 1993, he briefed Queen Elizabeth II on his republican plans. And in 1995, he presented a model to the parliament. And he supported a new Australian flag, without the Union Jack.

Third, he continued the economic reforms with privatisation of Qantas and the Commonwealth Bank; universal superannuation, now worth $3.4 trillion; enterprise bargaining, which energised productivity, and minimum award rates of pay; national competition policy, which boosted growth; trade liberalisation, which turbocharged competitiveness; and the Working Nation policy, which introduced mutual obligation in the provision of welfare.

Fourth, he deepened relations with Asia. He engaged in shuttle diplomacy to establish the APEC leaders meeting, an idea he presented to George HW Bush in Sydney in 1992 and then won support from other regional leaders. He negotiated a security treaty with Indonesia, the manifestation of his belief in finding security in, rather than from, Asia.

Fifth, he articulated a new identity for Australia, promoted arts and culture, recognised 60,000 years of Indigenous heritage, celebrated multiculturalism, and envisaged Australia as an outward-looking, confident, independent republic blazing its own path.

Keating saw politics and leadership as inexorably linked, as two sides of the same coin. He outlined his ambitions for leadership in an off-the-record address at the National Press Club in 1990, when he waxed lyrical about “doing the Placido Domingo”, trying to marry politics and policy.

As the former prime minister surveys Australia today, he sees a nation with unlimited potential but held back by lacklustre leadership and lack of ambition.

“Australia has lost its way,” Keating says. “We are at odds with our geography. We are the only nation in the world given an island continent and we have had choices about what we do with this great gift.”

He is a strong critic of the AUKUS partnership with the US and the UK to acquire nuclear-powered submarines. It is not simply a pro-China and anti-US view. It is about Australia’s independence and sovereignty, and a realpolitik approach to the region. He wants the US to remain engaged in the Asia-Pacific.

“I don’t believe that the US is able to maintain strategic hegemony in Asia with the rise of China,” Keating says. “So, I’ve taken the view, as far back as 20 years ago, that the US should be the framer and guarantor of the Atlantic but not of the Pacific. In Asia, it should be the conciliating and balancing power. And we need it to be.

“Scott Morrison, a pass-through prime minister of no policy account, wilfully and secretly alienated the sovereignty of his own country to that of another state – the US, a country his limited strategic vision cannot see beyond. His secret negotiation delivered to the US military effective strategic control of Australian naval forces, the sovereign policy options of the Australian nation.

“The most effective weapon you can have is not another bunch of submarines or missiles but a competent foreign policy. We are a frightened country. We continue running to a strategic guarantor – it used to be the UK and now it is the US. The fact that this has happened is a terrible indictment upon us and, of course, broadly they have had the complicity of the Labor Party.”

It would have been far better, Keating argues, to build the relationship with Indonesia rather than seek refuge in great and powerful friends and follow the US into Iraq and Afghanistan half a world away.

“The ANZUS-worded security agreement I put together with Indonesia was a golden asset for Australia, but John Howard lost it over East Timor,” he says. “We could have spent the last 25 years building a security and military relationship with Indonesia, a country that is centrally important to us strategically. How much more productive than the commitments to Iraq and Afghanistan by Howard. And how much safer would we be.”

This is an ex-prime minister still in the arena. This year, effectively solo, Keating waged a campaign to ensure the legislated increase in the superannuation guarantee to 10 per cent, and 12 per cent by 2025, was not jettisoned. It was a victory due to Keating’s relentless advocacy – nobody within Labor, the unions or industry packs a bigger punch.

In 1993, Keating led Labor to a fifth term, winning endorsement for his “big picture” program. He demolished John Hewson’s Fightback! package in an election that was also a judgment on the Coalition. Labor’s primary vote and parliamentary majority increased. No government has won a fifth term since.

Although he never scaled the heights of personal popularity, and could be polarising and divisive, Newspoll showed Australians respected Keating for his strength and vision. After 13 years in power, longer than any government since 1972, Labor was heavily defeated at the 1996 election.

Had he won in 1996, Keating argues, Australia would be a republic with a new flag. He would have taken control of the Murray-Darling Basin and restructured water pricing. Superannuation would have increased to 15 per cent, substantially lifting retirement incomes. He would have apologised to the stolen generations. He favours a treaty, which has “uprightness and power”, as the principal instrument for reconciliation.

“We would have been a radically different country,” he imagines. “With the economic changes and the competitive, open economy Labor created, we would have been a cosmopolitan republic finding our way in the Asian construct.”

Labor’s true believers remain spellbound by Keating’s approach to politics. But the parliamentary party has been more circumspect. While the 20th and 30th anniversaries of Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke’s governments were celebrated with gala events and commemorative dinners, no approach was made by the party to Keating for his anniversaries.

The party has, since 1996, never fully embraced the Hawke-Keating model. “Philosophically, Labor is moving towards the Hawke-Keating model,” Keating judges. “Anthony Albanese’s views about aspiration record a shift in sentiment inside Labor whereas the Bill Shorten model was essentially redistributive, taking economic resources from higher-income groups and distributing them to lower-income groups.

“Bob and I wanted to make the place wealthier, richer and do things to improve the creation and distribution of wealth, and at least provide a level playing field for everybody. We always had the sunny uplands in the policy. The sunny uplands, the notion where everybody found a place, disappeared at the last election and is reappearing somewhat now.”

Keating is the most respected of Labor’s living former leaders. His appeal transcends generations, as voters look for leadership and find both major parties wanting. Keating has admirers on the other side of politics, who regularly seek his counsel. Thirty years on, “the big picture” still resonates with many Australians.

“Politics today works within a narrow political spectrum of thoughts and policies,” Keating says. “There is no radical conception of policy now, partly because there is an absence of imagination. Imagination carries no premium, including in those most likely to profit from its power.

“What has happened with public life today is that the political professionals have taken over and now it is about playing a game within a bubble. Both the Coalition and the Labor Party have played into that bubble in a way, of course, that I absolutely shunned.”

Troy Bramston is the author of Paul Keating: The Big-Picture Leader (Scribe)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout