Anthony Albanese has turned Labor dealmaking into a fine art

Once a battle-hardened factional warrior, Anthony Albanese is using prime ministerial power to never lose on the issues that matter most.

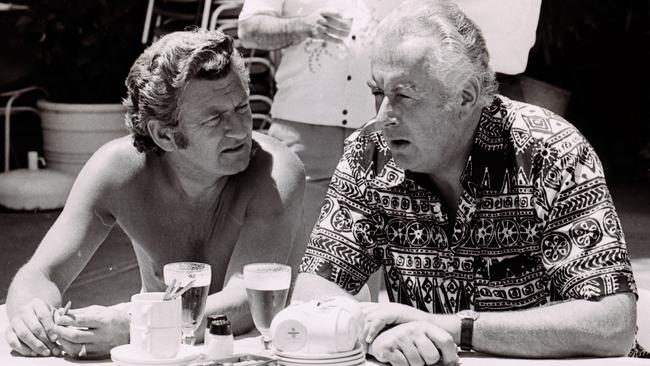

Labor moved south to the Florida Hotel at Terrigal in NSW for its next conference in February 1975, but kept the party going. Again there were loud shirts, bikinis and plenty of beer and wine being drunk. Hawke had an affair with Jim Cairns’ secretary, Glenda Bowden, and Cairns professed “a kind of love” for his adviser Junie Morosi.

Those heady days are long gone. No such displays of excess have been on display this week at the Brisbane Convention & Exhibition Centre for Labor’s 49th national conference. It is a much more disciplined and focused Labor Party these days, and that was the message they wanted to get across.

Emblazoned across the conference stage were the words “Working for Australia”. This framing for the conference was evident in Albanese’s opening address as he spoke of delivering on election promises, being focused on alleviating cost-of-living pressures and committed to the success of the voice referendum.

Albanese is a master factional operator and knows his way around party conferences. He attended his first national conference in 1986, as part of the always obstructionist national Left faction. They could always be counted on to oppose the reforms of Hawke and Paul Keating.

But now Albanese is Prime Minister. The political and factional calculations have changed. He cannot afford to be defeated on the conference floor by a combination of rank-and-file recalcitrance and trade union power plays. He ends the week not having been defeated on any significant issue, from AUKUS and Palestine to income tax cuts and refugee policy, or free trade.

Victory on the conference floor came via a combination of the steadfast national Right faction and most of the national Left faction. Hawke and Keating, and Whitlam too, often had to rely on the support of the Right and the unaligned or Centre Left faction (now extinct) to carry the day. Compromises were reached on key resolutions.

That Albanese can muster support from across the factions is a testament to his standing in the party. He is helped by a number of senior ministers also being factional powerbrokers. They are bound by cabinet and caucus decisions, and so must work the conference numbers to ensure they are not derailed. Conference decisions are meant to be binding on Labor governments.

This new internal Labor dynamic could not be stranger. Albanese was once in the permanent minority in the Left faction. Now Labor’s national Left has a workable majority of conference delegates for the first time since 1979. But they have split along union, state and personality fault lines. Rival slates of Left-aligned candidates nominated for the national executive – elected by the conference – whereas the Right united on their candidates.

Albanese, once a leader of the Hard Left faction, has worked closely with and relied on the Right faction to secure his policy agenda. He even attended and spoke at the national Right faction dinner on Thursday night. It would be unfathomable to the firebrand Albanese of 1986 that four decades later he would be prime minister and supporting nuclear-powered submarines.

The trilateral AUKUS defence pact is deeply unpopular within Labor. About 50 local Labor branches and electorate councils have passed resolutions either opposing it or calling for a review of it. This includes the Balmain branch, which founded the party in NSW and is in Albanese’s electorate of Grayndler.

On Friday, Defence Minister Richard Marles moved a resolution adding a statement in detail to the party’s platform supporting AUKUS. He and others worked furiously behind the scenes in recent weeks to allay concerns by the AMWU and ETU, and party branches, and emphasised industry development and job creation. They carried the day.

In the weeks leading up to the conference, senior party figures have engaged in a process of barnacle stripping to try to resolve issues so they do not make it to the floor for debate where the outcome may be uncertain. Nothing is guaranteed, of course, but the screws have been tightened on the most determined of party and union activists.

Penny Wong strengthened Labor’s language on Middle East policy by referring to Palestinian Territories as being “occupied” and Israeli settlements declared “illegal”. This is not so much a shift leftward as it represents the position of the EU, UK and the UN Security Council. Moreover, its advocates come from the Right faction: former foreign ministers Gareth Evans and Bob Carr.

Similar compromises were struck on free-trade agreements by supporting a parliamentary inquiry into the impact on local jobs to deal with union concerns and boosting the humanitarian migration intake to 20,000 per year to address party activist concerns over refugee policy.

Labor’s Environment Action Network was pushing for an end to native forest logging across Australia, an end to land clearing and also a commitment to halve methane emissions from agriculture by 2030. This campaign, despite having the support of 300 local party branches, only went some way towards this. Party figures were not wanting to completely stifle debate at the conference. Wayne Swan, in his opening address as president, spoke about how Labor is the only party to allow the media to observe all proceedings. Debate is a sign of a healthy and vibrant party, he argued. But the unstated point was: the leadership has to win.

This is Labor’s first national conference to take place while the party is in government since 2011. The last national conference was five years ago, in Adelaide. It is Albanese’s first national conference as party leader and Prime Minister. In his opening address, he said Labor must be a party of power and not protest. He wants to lead a long-term government.

When Labor was last in power, it came undone over the competing ambitions and internecine warfare between Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard. The lessons of those years have been learnt, ministers insist, and any leadership ambitions are well hidden. Nobody is agitating about the leadership.

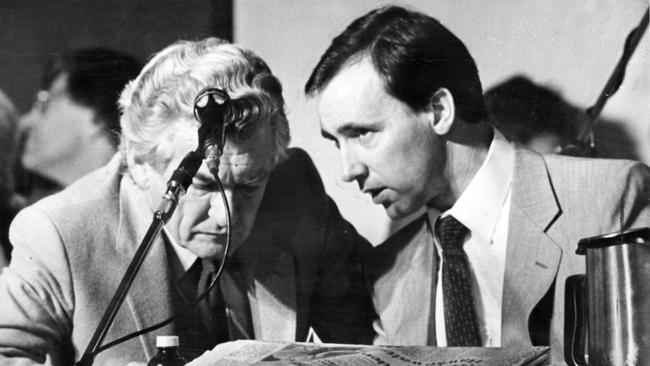

National conferences have often been a staging ground for future leaders to strut their stuff. Sometimes leadership challenges can spill out into the open. This is no better illustrated than the confrontation between Hawke and Bill Hayden at the 1979 national conference in Adelaide.

Hawke, then ACTU president, proposed that Labor pledge to hold a referendum to enable the government to regulate the setting of prices and incomes. Hayden initially supported Hawke but then changed his mind. Hayden joined forces with the Left and defeated Hawke, who had the backing of the Right.

That evening, all hell broke loose. At the Rotunda Bar at the Gateway Inn, Hawke let fly with his bar-room assessment of Hayden. With a belly full of grog, Hawke said: “As far as I’m concerned Bill Hayden is dead. Hayden is a lying c… with a limited future.”

At the party’s next national conference, at the Lakeside Hotel in Canberra in July 1982, the tensions between Hawke and Hayden exploded. Hawke, now the Labor MP for Wills, told journalists the party would do better if he were leader. Hayden called a caucus leadership ballot nine days later and defeated Hawke 42 votes to 37.

Labor’s 30th federal conference (as it was called then) at Surfers Paradise was a relatively smaller event, with Hawke in the chair. Delegates sat at tables and went through the agenda over several days. This week’s jamboree in Brisbane is the largest political gathering in Australia, with about 2000 delegates, observers and media attending.

In 1973, Whitlam faced intense pressure to take a hard line against US military forces and joint facilities in Australia. Trade unions were also pushing the government for a more interventionist labour market policy and to step in to resolve disputes between unions and companies. Some things never change.

In 2023, Albanese is dealing with opposition to closer military and intelligence co-operation between Australia and the US, of which AUKUS is a key part, and trade union demands for greater industry protection, a bigger say in workplaces, and improved wages and conditions.

The Labor conference is still very much a federation of state branches that decide how their representatives are elected. There are no directly elected or allocated union delegates; ACTU leaders had to suspend standing orders to speak. But union officials do dominate state delegations. There are 402 delegates in total with three non-voting (the president and two vice-presidents).

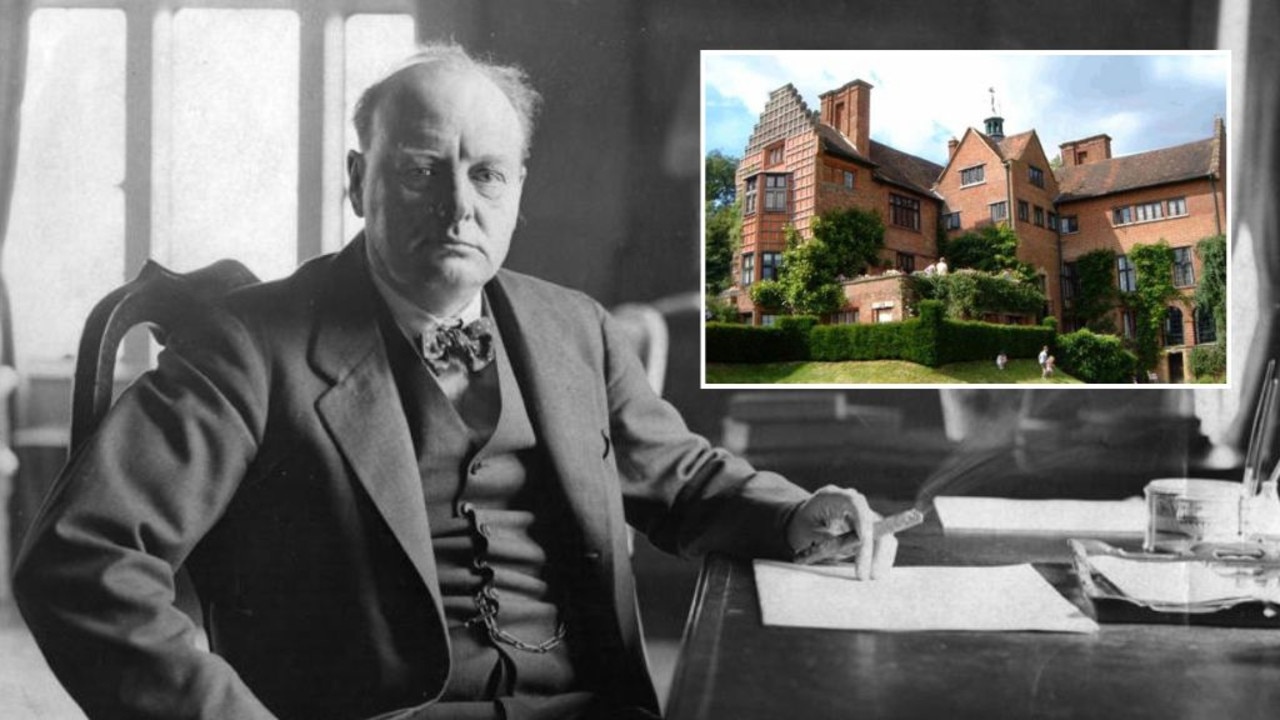

In March 1963, Labor’s federal conference – then made up of 36 delegates – met in Canberra to determine policy on the US naval communications station at North West Cape. Party leader Arthur Calwell and deputy leader Whitlam supported the station with joint US-Australia oversight. Their position was adopted.

However, they were famously photographed waiting beneath a lamppost outside the Kingston Hotel in Canberra while the matter was determined.

Journalist Alan Reid organised for them to be photographed and Robert Menzies railed against “36 faceless men” determining Labor policy.

The Labor conference is today still dominated by unions, state branch representatives and factional operators. But the parliamentary leadership is determined to preside over a party that balances principle with power, and steers the conference in a direction that supports their agenda.

Albanese, once a battle-hardened factional warrior who lost more debates than he won at party conferences, is using the subtle art of prime ministerial power to never lose on the issues that matter most.

The last time Labor held its national conference in Queensland was in July 1973 at the Chevron Hotel in Surfers Paradise. Gough Whitlam was prime minister. Bob Hawke was party president. Ministers, party officials, delegates and observers wore Hawaiian shirts, milled poolside between proceedings, and drank and partied.