Much is at stake for Anthony Albanese at ALP national conference with party restless on key issues

Labor’s national conferences are freighted with history, steeped in tribal sentiment and an exercise in grassroots democracy in contest with supreme factional management.

The party’s 49th national conference, and the first held since 2018, is the strangest in a generation. When the 402 delegates assemble in Brisbane on Thursday, Labor’s national Left faction will have a workable majority for the first time since 1979.

But divisions within the Left, based on personality, geography and union allegiance, make furious agreement unlikely.

Anthony Albanese is no stranger to national conferences. He was a delegate to the 1986 national conference in Hobart and voted with his then radical, obdurate and always obstructionist Left faction to abandon the float of the dollar and return to a regulated exchange rate. The Left also opposed wage restraint and fiscal consolidation.

Now, Albanese leads the party and is Prime Minister. The irony has not been lost on those with a cursory knowledge of the party’s history.

It is now Albanese’s agenda that is up in lights. Talks have taken place for months to ensure his government is not embarrassed with a resolution that must force a change in policy.

It is the Left faction that, again, is a thorn in the leader’s side. But it is mistaken to think it is only the Left that is rousing opposition.

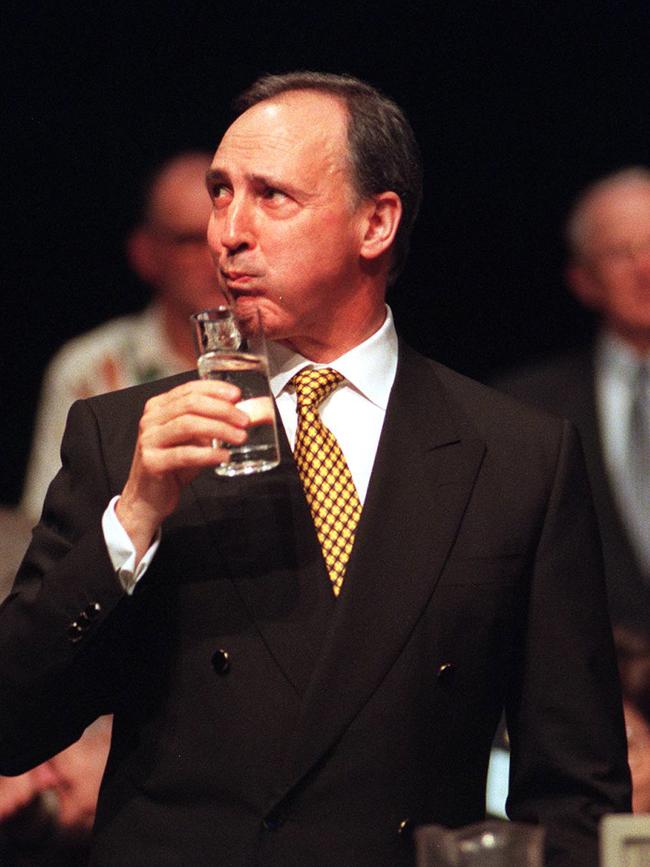

The opposition to AUKUS is being led by Paul Keating, the favoured son of the NSW Right faction. Bob Carr and Gareth Evans, respectively from the NSW Right and Victorian Right, have forced the change in position on Israel-Palestine.

In any event, party chiefs are determined to avoid any resolution that runs counter to the policies adopted by the cabinet and caucus. They are also eager to avoid dramatic speeches of defiance on the conference floor, although that will be harder to control. It is expected the leader will, as ever, prevail.

Labor’s national conferences are vested with enormous power and authority. The party platform is sacrosanct; it is binding on the parliamentary party. MPs, union and faction chiefs prize the chance to be a delegate. It was not until the late 1960s that party leaders had the right to attend and vote as a delegate.

Albanese has been engaged in barnacle stripping ahead of the national conference, seeking to resolve contentious policy issues by drawing on the support of senior ministers from both the Left and Right factions, and bolstered by union heavyweights and faction bosses. These are always closed-door discussions where a mix of flattery, pressure and compromise is used.

Deals have been brokered to avoid floor fights on Middle East policy by labelling Israeli settlements as “illegal” and referring to Palestinian territories as “occupied”; supporting a parliamentary inquiry into the impact of free trade agreements on local jobs, and; increasing the humanitarian migration intake to 20,000 per year to allay concerns over refugee policy. But it may not stop some of the delegates seeking to relitigate these matters.

Indeed, several issues are still being worked through and the possibility of a floor confrontation cannot be ruled out. The most likely is opposition to the trilateral nuclear defence pact, AUKUS, which most Labor Party members oppose.

Others include: increased funding for local government; reviewing legislated income tax cuts, and; a ban on native forest logging and land clearing, and halving methane emissions from agriculture by 2030. Many in Labor believe it is the sign of a healthy party to have policy debates ventilated in public.

It strengthens the standing of the party leader and senior figures if they can emerge with an endorsement of their policy positions. Attempts to stifle debate can be counter-productive. Just ask Kevin Rudd, who insisted on no votes at all at the party’s national conference in 2009.

A generation ago, it was very different. Bob Hawke and Paul Keating battled through a series of national conferences in the 1980s and ’90s, with the Left faction routinely opposed to their reformist agenda.

These conferences were like an epic colosseum contest where warriors did battle with everything on the line. It was always a close-run thing for the then prime minister and treasurer.

Whether it was tariff reductions or privatisation of government-owned airlines or banks, the float of the dollar and deregulation of the financial sector, the reintroduction of university fees or selling uranium to foreign markets, or the joint defence facilities, the Left was opposed. Hawke and Keating only prevailed because of the combined votes of Right and (now defunct) Centre-Left factions.

Labor’s Right faction, which still commands a majority of MPs in the federal parliamentary party (or caucus), has a historical default position of supporting the leader.

It has provided the essential support necessary for generations of leaders from Gough Whitlam to Hawke and Keating, and to Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard, to enable them to almost always prevail at national conferences. This ethos has not changed.

Labor’s Left faction, of which Albanese was (and still is unofficially) a leader of immense influence and dexterity, remains the irritant for the party leader.

Well, not all of the Left, only part of the Left. As I revealed last week, Labor’s Left faction has split and rival camps, remnants of the so-called Hard and Soft Left sub-factions, have put forward rival slates of candidates for the party’s national executive elections. The national conference will be a test of the capacities of Albanese and his senior ministers to secure their agenda against opposition from within their own party ranks.

Labor’s grassroots members and affiliated unions are restless, yet know they are fighting a losing battle. But for Albanese, who was often on the losing side at party conferences, winning is now all that matters.