Switch the salt: new global guidelines urge uptake of salt substitutes

The World Health Organisation has issued new guidelines urging people to swap regular table and cooking salt for lower sodium substitutes at home.

Australians are being urged to switch table salt for lower-sodium salt substitutes at home in a global effort to improve heart health, but there are concerns the new guidelines do not go far enough.

The World Health Organisation is leading the push and urging member states to adopt the new guidelines, which are being released on Tuesday. The authority hopes that by urging a straight substitution rather than a complete cut, people would find it less daunting to make the switch. According to the WHO, 1.9 million deaths are linked annually to high sodium intake.

As part of its new guidelines, it will recommend people limit sodium to below 2gm a day. The latest estimate suggests people consume double that, at around 4.3gm a day.

WHO members have been working to slash sodium intake by 30 per cent by 2030, but progress towards that goal has been slow. To get there, it will now suggest people switch salt they use at home for a potassium-rich salt substitutes. Doing so, according to the WHO, would reduce blood pressure and the risk of cardiovascular disease globally.

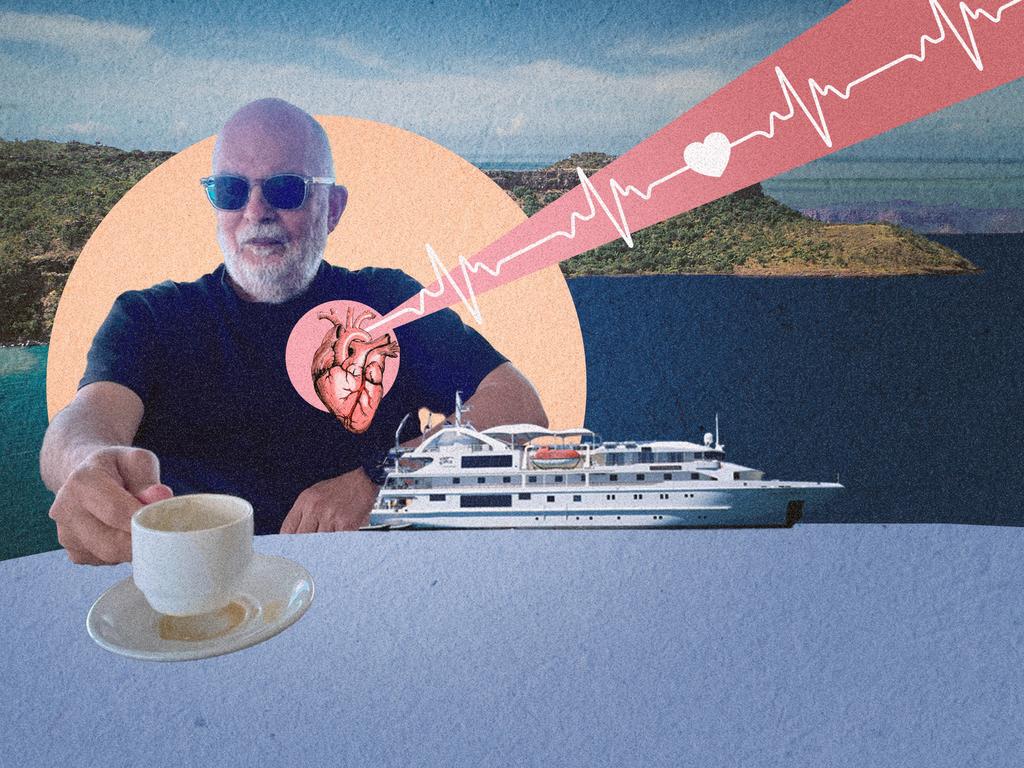

“Basically, everyone in the world eats way more salt than they should, and salt causes high blood pressure and high blood pressure is the single biggest modifiable risk factor for premature deaths and disability in the whole world,” said Bruce Neal, professor of medicine at the University of NSW and a director at the George Institute for Global Health.

Researchers at the institute have been studying salt, its impact on human health, and ways to reduce it for years. It has also been heavily involved in the WHO’s new guidance, which Dr Neal helped to review and has described as “really significant”.

“It’s making a specific recommendation saying that if you’re going to add salt to foods in the home, then don’t use regular salt, which is 100 per cent sodium chloride, use potassium-enriched salt where some of the sodium chloride has been replaced with potassium chloride,” Dr Neal said.

However, he did not think the recommendations went far enough, especially in Australia where he said there was a large uptake of pre-packaged foods where salt was already added. For that reason, he would prefer the guidance to be extended to the food industry more broadly. “For Australia, the guideline falls a bit short, to be quite honest,” he said.

“Most of the food we eat now is not food we prepare from … base ingredients at home, it’s food we buy from a supermarket or from a restaurant chain that is already majority pre-prepared.

“The guideline is only making a recommendation around that 20 per cent or so of salt that comes into the home. That’s still important … but it won’t be as big a benefit as if the guideline had said the food industry should also switch from using regular salt to using potassium rich salt. I still don’t really understand why WHO has chosen to make a recommendation that only relates to so-called discretionary salt. It doesn’t really make any sense to me.”

There would also need to be greater availability of the products if Australia were to adopt the guidelines. The substitutes are often marketed as “lite salt”, “heart-salt”, or have “salt substitute” written on them and are used in the exact same way as regular salt.

However, potassium-rich substitutes are not recommended for people who have advanced kidney disease. Potassium is found naturally in fruits and vegetables and helps your muscles to work. Your kidneys remove excess levels of the mineral once your body has used what it needs. However, people with kidney disease cannot remove the extra potassium effectively, which can mean it stays in their blood, putting them at risk of hyperkalemia (high potassium), which can be very dangerous and even fatal in extreme cases.

Dr Neal said this was certainly not an intervention appropriate for people with advanced kidney disease but, he pointed out, that would relate to only a small percentage of the population.

Fiona Willer, president of Dietitians Australia, said she suspected the substitution, if adopted, could actually help to identify more people who could be unknowingly living with kidney disease. She said anyone who did switch to a low-sodium salt alternative and experienced poor health should contact their doctor.

“If you’re having headaches, if you’re having urinary issues, you know you should be checking in with your GP to see if there’s anything going awry, and they can quite quickly determine through blood tests and urine tests whether you should be referred to a specialist,” Dr Willer said. “So it’s going to bring some of those people out of the woodwork with this substitution and the long-term goal is that it reduces the stroke and cardiovascular disease risk within the population. Any benefits that we realise will be in decades rather than more immediate.”

Dr Willer said dietitians had been recommending low-sodium substitutes to patients with high blood pressure for decades and she welcomed this latest move, which will finally provide clear and consistent advice on using potassium-enriched salt. It is now up to authorities in individual countries to determine whether they will adopt the guidelines. Dr Willer, however, would prefer to see people replace salt with other natural flavour enhancers like herbs and spices, as opposed to a salt alternative.

“Everything’s going to taste a bit bland for a couple of weeks, but then within that time, our tastebuds will regenerate and different sorts come out and you can taste a lot more after two weeks on a lower salt diet,” she said.

She would also like to see people trying to cook more meals at home, suggesting doing so using a salt alternative or ditching it entirely would further help to reduce a person’s sodium intake.

“When we’re talking about when we’re changing things with food, that can make people a little anxious about what they’re eating. It can also bring out some more sort of dysregulated eating and people and if you’re struggling with your food habits or dietary practices, check in with a dietitian or talk to your GP.”

The WHO will also release guidance to help people make the transition.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout