‘Eighty is a weird land to be in’: Michael Palin is still looking on the bright side of life

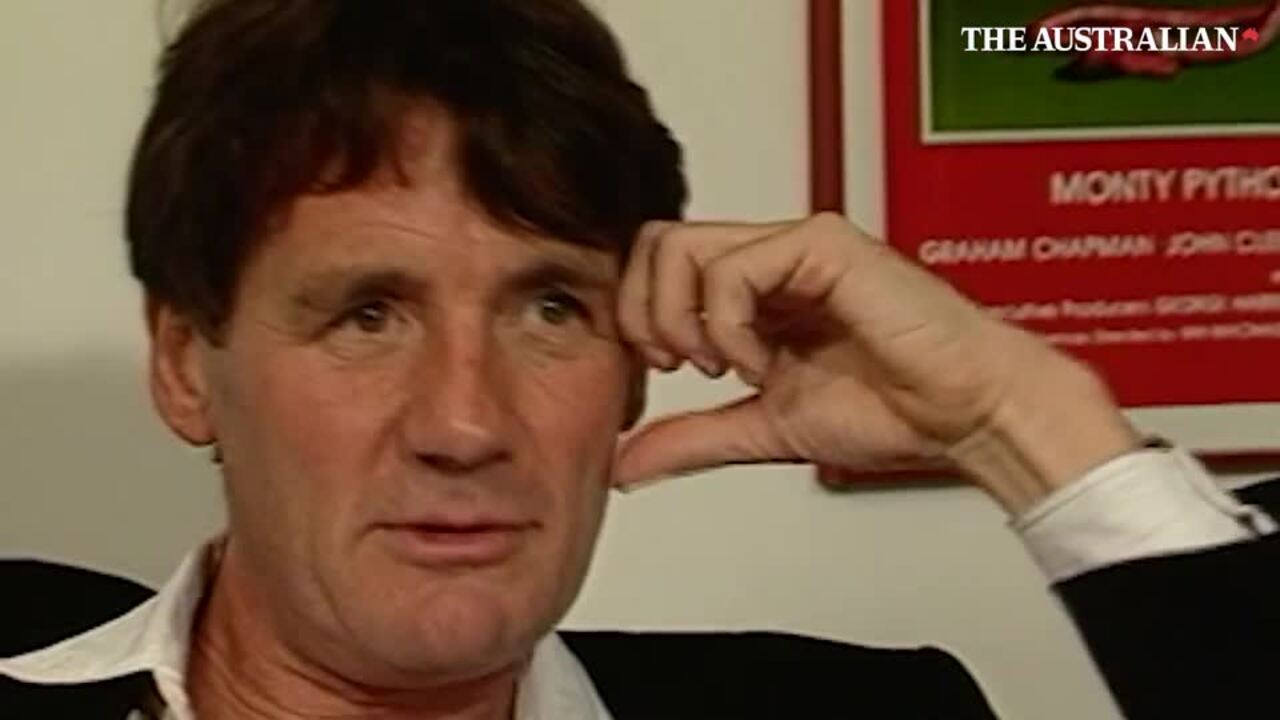

He’s seen up close how people live around the world. So how is the Monty Python star faring at 81?

On the question of solitude, Sir Michael Palin is pragmatic. By his own assessment, the Monty Python star is a mostly contented man with a mostly centred base. He pounds the same London paths he ran for years, and now walks, frequents a clutch of local eateries and has lived in one house for decades, a familiar respite at the end of many journeys.

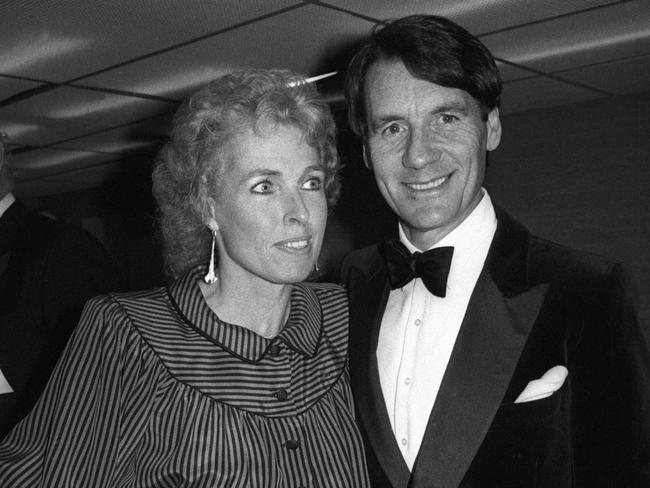

At 81, there’s a reassuring pattern to parts of his life. Having visited swathes of the globe for a succession of TV programs and books, he has written about the joy of returning home, and specifically to his wife Helen, a former bereavement counsellor who, he notes in the dedication to his most recent volume of diaries, There and Back, “was always there when I got back”.

But last year Helen died. Now when Palin returns home it is to a space that is both dear and hollow. “There’s a certain emptiness,” he concedes of the start of his ninth decade, a period in which his 57-year title of husband has been usurped by the still unfamiliar sobriquet of widower. “We’d known each other for 60 years and during that time had built up a lot of unspoken connections. And (now) I find there’s someone I want to talk to but I can’t talk to anymore.”

Like most of his contemporaries, the former Monty Python star is becoming familiar with bereavement. His sister Angela died in 1987, and There and Back, which is his fourth volume of diaries and covers the years 1999 to 2009, is sprinkled with references to the passing of mates, former Beatle George Harrison among them. More recently “three or four good friends, who are the bedrock of my life, they have died”.

But the loss of his life partner, after several years of illness, was something else. “It’s like having a limb removed,” he says from his London home, which in many ways remains as it was when Helen was alive. Her belongings are in the cupboards, her photos hang from the walls. Eighteen months on, in some ways she is still with him.

“After I’ve been out to a late do, I come back and I find myself saying ‘Well that was a waste of time’ or ‘I met some interesting people you would have hated’, the little things we had in our relationship,” he says of the conversations he sometimes enacts in her imagined presence. Or as he also says: “She’s in my head rather than on the sofa.”

And it’s from there that his sensible wife is somehow cajoling him to look forward. “I wouldn’t say I’ve got a clear path ahead of me,” Palin concedes of his post-Helen world. “I’ve been working very hard since she died so that’s been a good distraction. Helen was a very pragmatic person. She wouldn’t have wanted me to go around the house moping so I remember her spirit and what she might be saying to me.”

Partly that’s continuing with the familiar. “I go on the same walks, to the same restaurants that I went to with her. I’m not doing that in a melancholy way. She would have wanted me to carry on with my life.” But also it’s keeping busy, socially and with work. As he says: “How you readjust is entirely up to you.”

Like his present, love and loss are recurring themes in Palin’s There and Back years, which span the birth of a new millennium. There is the melancholy of his children leaving home, and his utter joy at becoming a grandfather. (His first grandchild Archie, who is now 18, is indexed in There and Back with multiple subheadings including “MP besotted with”, “MP looks after”, “greets MP” and “talks to Grandpa”.)

“I’ve now got four grandchildren and it’s just a fact that the first one gets all the attention. It’s the first time you have grandfatherly feelings. It’s the first time you’ve been ‘grand’ anything,” Palin says now of the contemporaneous gushes of love that are documented in Archie’s early years. (“See Archie for the first time,” he writes on a Saturday in March 2006. “First impression is of a ruddy little face, flushed dark against his white baby-suit … hold him and feel very proud and happy.”) As he says today: “There’s something about the arrival of a new life … they’re tears of gratitude that life goes on.”

It’s a continuum on which Palin has a particular view. From circumnavigating the globe in 80 days to venturing through the Himalayas, his work travels have enabled him to glimpse inside the lives of people in countless countries. Now that he is of a certain age, some of what he has seen feels personal.

“In a lot of non-Western societies, ageing is considered a sign of increasing wisdom and experience … and people are still part of a community. They’re seen as people who have important advice,” he says.

“I don’t really feel that here in quite the same way. Once you can’t work with technology, which I can’t, you’re almost gagged, you’re not part of it. This is a very different thing to what I saw growing up.”

Having been raised in a world of words, he is confounded by some of the technological changes that have become essential parts of life in the 2020s. “Yes, a lot of search engines are really brilliant,” he concedes. But some instructions would help, thank you kindly. “You buy things and then it will give you an indication of how to use it,” he says, his normal geniality briefly shadowed by irritation. “But nobody tells you how to use the internet.”

To be Michael Palin at 81 is a mix of ease and uncertainty. “Eighty is a weird land to be in. People say to you ‘you’re a very young 70’. No one ever says ‘you’re a very young 80’,” he laughs.

What does happiness look like at 81, compared to say 41 or 21? “I think it’s a lot easier and more comfortable. I feel much less competitive than I did then. I had more opportunities then but I certainly feel less pressure. After 80 you’re mainly more concerned about getting up in the morning and not falling over.”

Re-reading his diaries, he was struck by the satisfaction of his world. “It’s kind of reinforced the way I live. When I read the diaries, they’re the diaries of an enormously contented man with reasonable doubts about work. On the whole I am a happy man through the diaries, so in a way it makes me feel well, my life it’s essentially sort of unsensational, we’ve been in the same house for 50-odd years.”

Alone in the home he shared with Helen, life goes on. “It feels okay. It’s just there’s something missing. You can’t have music or the news going all the time. There’s a certain emptiness. But it’s okay. I’m quite good at being on my own.”

Keeping busy and staying socially connected help. “It’s very important not to hide away, to go out and meet people and just chew the fat,” he says. “So long as I am working then I can deal with the long silences in the house and all of that.”

It helps, too, that he is able to seize occasions of lightness. “I had a really nice moment just after Helen had died, and I had to register her death,” he says. Standing in line with him that day was a young family waiting to register a birth. “A couple came in with a very small, newborn baby clasped to the man’s chest. We chatted and I just thought it was very (symbolic) that as I was recording the departure of one they were recording the arrival of another.”

For Palin, at this saddest moment, life’s continuum was evidenced by these new parents, with whom he has remained in contact, and their tiny baby. “I feel a bit of Helen passed into her.”

That he was able to find sunshine at such a bleak time says much about his sense of proportion. “I think you have to accept the sadness,” he says when asked about balancing joy with the losses that inevitably mount with age. “It happens, you can’t deny it. You have to be glad that you can still keep going and you have to enjoy the memories a lot more. That’s the thing about old age. You have a lot of memories – and that’s what the diaries are all about – and relish those memories and say, ‘Well, we had good days, we had bad days, but we were blessed with knowing each other’.

“And being generally positive, that’s the key to it. I think I’m very lucky. I’ve got reasonably good health. I live in a city that’s full of life and energy and things to see. I feel very, very blessed in many ways.”

There and Back: Diaries 1999-2009 by Michael Palin (W&N)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout