A conversation with Monty Python legend Michael Palin on comedy, travel, diaries and family

As Michael Palin was getting started with Monty Python, a relative handed over a trove of family records. It wasn’t until 30 years later that the comedic legend set out to find out more about a man he had heard little about.

When Michael Palin left university, the only thing he wanted to do was write and perform comedy. He had experience in theatres, revues and festivals. By the mid-1960s he was writing for various television shows, and joined with Eric Idle and Terry Jones to write and perform in the children’s series Do Not Adjust Your Set (1967-69).

The big break came with Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969-74). Palin, Idle and Jones teamed up with John Cleese and Graham Chapman, with whom he had appeared in How to Irritate People (1969), and Terry Gilliam. It was comedy magic. After 45 episodes, they moved into film with Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) and Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979).

“We had very similar backgrounds,” Palin, 80, recalls of his fellow Pythons in an interview with Inquirer. “We had all gone to university. We were middle-class boys; we weren’t rich kids. All of us, either at Oxford or Cambridge, had found that we could entertain people. And it was a time when everything was up for grabs – you could make jokes about anyone or anything.

“In 1969, John rang me up and said, ‘Look, why don’t we all get together?’ At that time Terry Gilliam had come over and was a very important part of the mix because his animation was so sharp and radical and different, and very funny. The BBC didn’t understand what we were doing and didn’t worry if nobody saw the show, near midnight on a Sunday.”

Several of Palin’s sketches are part of absurdist comedy legend, including the Fish-Slapping Dance, the Dead Parrot and Spanish Inquisition sketches, the Bicycle Repair Man superhero and singing The Lumberjack Song.

“The Fish-Slapping Dance was one of those that I love,” Palin recalls. “I was going to be knocked into the waters of a canal by John Cleese at the end of the sketch. But when we did the taping, the canal had drained, so actually I fell 15 feet before I hit the water. That’s what made it so funny.

“There is one called The Cheese Shop that I’m particularly fond of. My character is running a cheese shop, it’s the best cheese shop in the district, yet he has none of the cheeses that John Cleese wants. And John goes through, brilliantly, an enormous number of cheeses that he does not have. John and I could never do that without cracking up.”

It is almost impossible to imagine the Pythons being able to perform this comedy today. People are too easily offended when no offence is intended. The rush to judgment and cancel culture, fuelled by social media, are in overdrive.

“There isn’t much like it being made nowadays, which I think is odd,” Palin says. “We could do all sorts of things: we could dress as women, we could knock people off bicycles, we could have bare-breasted ladies selling newspapers with men not noticing. The BBC wouldn’t let us do that now. The sheer joy of Python wouldn’t be possible.”

As Palin was getting started with Monty Python, a relative handed over a trove of family records, including diaries kept by his great-uncle Harry who was killed at the Battle of the Somme in September 1916. But it was not until 30 years later that Palin set out to find out more about a man he had heard little about.

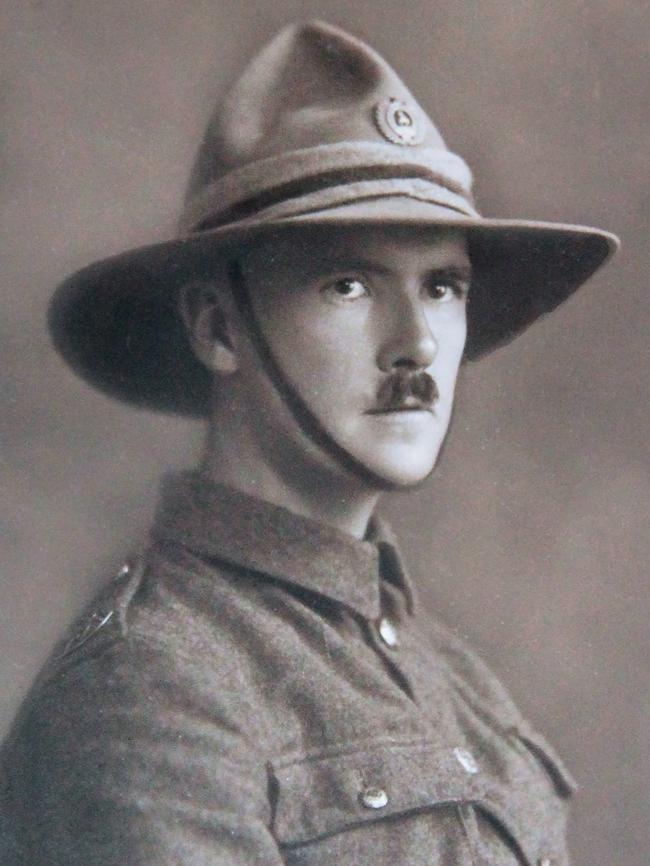

“Among the family records was this picture of a young soldier,” Palin remembers. “I asked who it was and it was always slightly dismissed. ‘That’s Great-Uncle Harry. He died at the Somme.’ And that was the end of it. In 2008, I decided to see what more could be found out, if anything, about this shadowy figure who was the face in the photograph.”

The journey of discovery included visits to archives, enlisting the help of researchers and walking the paths that Harry walked. He had attended the same school as generations of Palins, Shrewsbury, travelled to India to work on the railways and then a tea estate, immigrated to New Zealand and worked on a farm, and then enlisted for World War I.

Filmmaker Peter Jackson, who built a huge image database for his documentary They Shall Not Grow Old (2018), located probable and possible photos of Harry in uniform. Harry had travelled through Europe and the Middle East, was with the Allied troops at Gallipoli, and later in France. Examining photos, diaries and letters helped understand Harry.

“I think the reason that he joined up was because all his friends wanted to,” Palin suggests. “The propaganda throughout the war was also a very powerful tool. They were told it would be over by Christmas and it would be free passage back to Europe. Harry was happiest, I think, when he was among his friends.”

Harry was not especially reflective in his writings but there are glimpses of the kind of person he was. His parents were elderly and there was an 11-year age gap with his closest sibling, Eleanor. Palin suspects he was raised without much affection or attention, which may explain his escape from London and distance from his family.

His diaries offer further insights. He had a girlfriend, Margie Sale, to whom he had proposed marriage. But she turned him down. The diaries, written in pencil, also chronicle the horrors of war alongside the routine of everyday life in the dugouts.

“To start with, I found them frustrating because they were very staccato,” Palin says. “He was not able to describe situations in the way that Wilfred Owen or Robert Graves might have done, that wasn’t his thing. But it’s all there. He doesn’t have to state it. The more I read of the diaries, the more I felt what he was going through. Very often the diaries deal with ordinary life in the trenches and, amazingly, getting letters and gifts from home.

“Then there are the moments when he writes about taking ordinance up the hill and the Turks firing down on them, and that’s like an almost everyday thing. He sees horrendous action in which a lot of his friends are killed. And, interestingly, the only time he ever uses capitals in his scribble diary is when he writes ‘HELL’. He says, ‘What we were going through was HELL’. And, he didn’t need much more than that.

“He didn’t put it into context but what made it powerful was that he gave a list of his friends who had been killed. That was his way of writing it. So, in the end, I found that you had to interpret them. You had to read between the lines to get the sense of why he didn’t write about this and why he did write about that. And from that, I got to know him.”

In 1969, having given up smoking, Palin was looking for a hobby and took up diary writing. At 9am most mornings, he writes up an account of the previous day. Three volumes documenting 1969 to 1998 have been published, and a fourth will be released in 2024. They offer a window into Palin’s family life, the Python years, his travel documentaries, book writing and films such as A Fish Called Wanda (1988).

“Once you’ve started, it’s very difficult to know when you should stop,” he says. “The difficult days were the first three months. Monty Python was being formed at that time. Fortunately, I just kept it going, even though I was quite busy, and it had a bit of momentum, I felt I had to keep it up if it was going to be worth anything. It became part of morning life.”

Like Harry, he is also inquisitive about the world. His travel documentaries, beginning with Around the World in 80 Days with Michael Palin (1989), have taken him almost everywhere from the North and South poles, through Europe and South America, to Africa and the Middle East, the Asia-Pacific and Americas, and recently to North Korea and Iraq. He filmed in Nigeria last month.

“Harry spent his early life in a small village in Hertford,” Palin says. “I spent my early life in Sheffield, an industrial town in the north of England. I had no idea of ever really going abroad or even going to London to work. I didn’t go abroad until I was 19 or 20, on holiday in Austria. I really didn’t do much travelling until I was in my 30s, about the same age as Harry when he died.

“My response when I was able to travel was that ‘I want to do more of this’. I’ve got a feeling that Harry’s travels – he had gone to India and New Zealand – seemed to suggest a spirit of adventure. There might be less of the conservative respectability of Victorian England you could find in a new country.

“That’s partly why I travel. I travel to countries to find out how they are different and why they feel different, and that makes you look differently on your own country and your own experience.

“Harry going out there to find a better place is not far from myself.”

There are several threads of comparison between Palin’s life and that of Harry, not least a love of travel and adventure, and diary writing, but perhaps most of all it is the elemental things: curiosity, restlessness, an independence of mind and wanting to live the life they have chosen.

“The desire to find what he wanted to do and reluctance to be pushed into a respectable job absolutely accorded with me,” Palin says. “I was aware that once I left university, I had to be able to fit in to some career pattern. So, I applied to the BBC for a general traineeship. They were usually very bright people who went into administration and would rise up to the top of the BBC.

“I told my father I was going for this interview and he thought that was very good. But I wasn’t happy. I knew it wasn’t for me. The interview was disastrous. I just wanted to do comedy. That was the thing that really kept me going at that time. Harry didn’t want to be pinned down either. And in my life, I have nearly always had absolute control of what I’ve done.

“The impetus, whether it be acting or writing or presenting, has come from me. I’ve felt very fortunate that I could be the one who instigates that. I made some money. Harry never made any money. But there was a similar reluctance to be told what to do by people. That accords with me. I wish I had met him.”

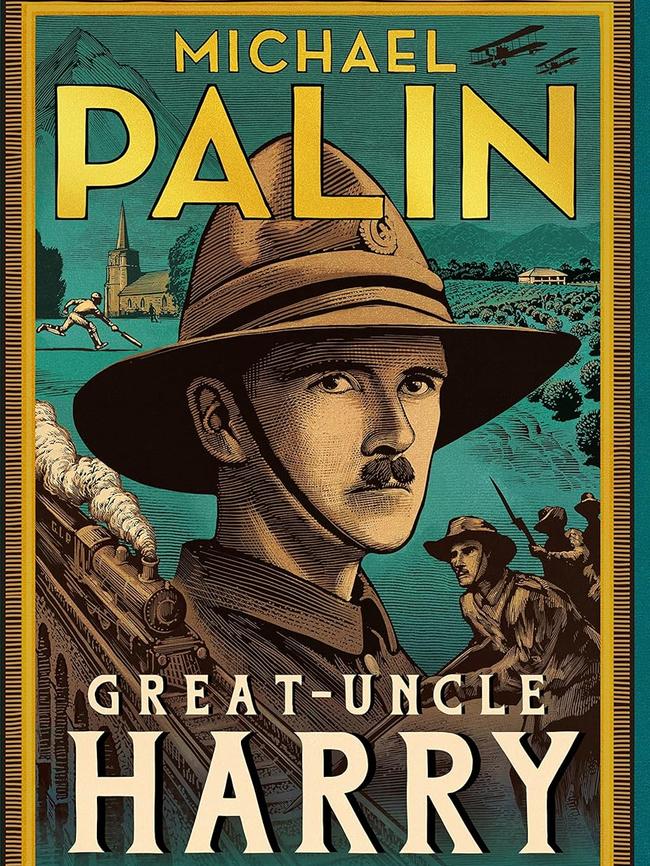

Michael Palin’s Great-Uncle Harry: A Tale of War and Empire is published by Penguin Random House.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout