Michael Palin: on grief, travel, writing and his Monty Python legacy

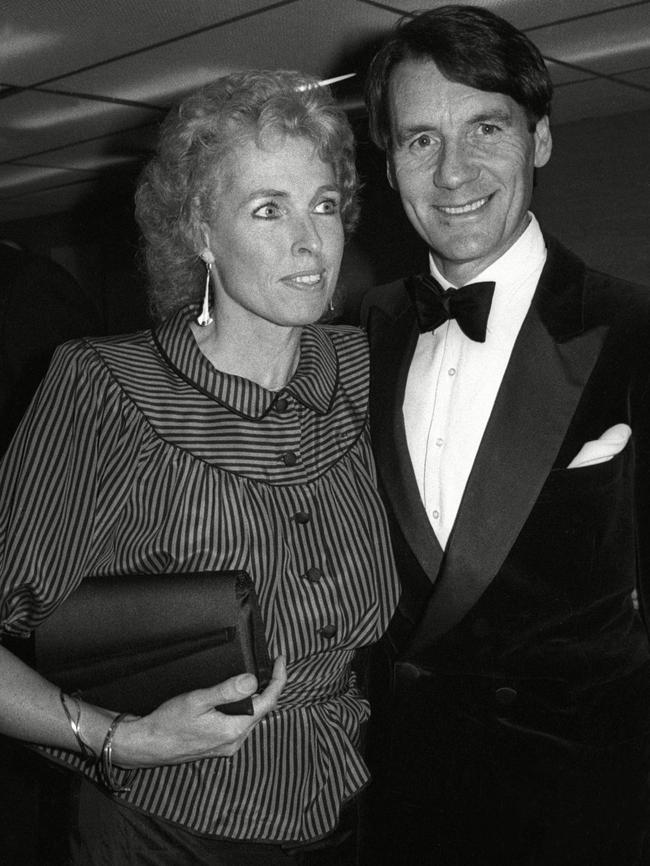

The Monty Python star lost his wife earlier this year. But he refuses to grumble and has chosen instead to celebrate a remarkable partnership.

Michael Palin answers the door of the north London house he and his wife, Helen, moved into more than 50 years ago looking ten years younger than he actually is, which is 80. Fit and slim and in trainers, he offers to make me a coffee and directs me to the loo, where I find two framed certificates, for coming third in an obstacle race and second in a wheelbarrow race, so long ago the print had faded and I could not make out where these glittering prizes were won.

The accolades, of course, did not stop there. He is extremely distinguished. A knight commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, a former president of the Royal Geographical Society, a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, holder of a Bafta fellowship. An asteroid and two locomotives are named after him. He is the Greatest Living Yorkshireman and Britain’s Nicest Man. He is also immeasurably famous as a comedian, a traveller, a writer, an arts documentary maker and a national treasure, if we must.

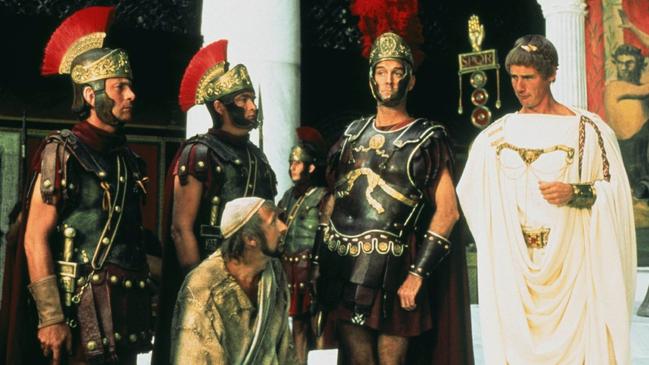

He wears his honours lightly, to the point of invisibility, and manages to be unfailingly engaging with everyone he meets – North Korean border guards, Sufis in Sudan, Prince João Maria of Orléans-Bragança in Brazil, yak herders in Tibet. It is difficult to imagine his geniality failing, but I think I have once seen him angry, on television more than 40 years ago, when some worthy people were being patronising about Monty Python’s Life of Brian.

We exchange condolences on the loss of our spouses, mine nearly four years ago, Helen, of kidney failure, aged 80, in May. They had been married for 57 years. How is he getting on?

“It’s the little things, isn’t it, that get you?”

I said I could cope with the existential terror but not with defrosting the freezer.

“Funny you should say that – my daughter’s just been round to do mine.”

Can we talk about Helen, I ask, if that’s OK with you?

“Yes. I’m happy to talk about it. In fact it’s quite useful.”

Palin first met Helen Gibbins in 1959, when they were both teenagers, on holiday with their families in Southwold, Suffolk, on England’s south-east coast. They met again a year later and it all got more intense. Passionate letters were exchanged but they didn’t intersect again until he arrived at Oxford University to study modern history. She happened to be a friend of a friend who was a friend of a friend. They met on his first day there and that was that. They married in their twenties, and have three children and four grandchildren.

“She had been so ill and disabled for so many years, relying on dialysis to keep her alive, and she took the decision, along with the children and the doctors, to give it up. The last ten days of her life – I’ve never seen her happier in a way. She’d accepted it, we’d accepted it, she was in a wonderful hospice. The children and grandchildren had all come to see her, so her death was a great deliverance for her.” It sounds like the good death we all hope for. It is, nevertheless, a death. “When someone’s gone, someone who has been so much part of your life for the past 60 years, you can’t believe they’re not there to enjoy a little joke, or an observation, or a bitch about somebody,” he says. “A great sort of emptiness comes in.”

For more than 30 years Helen was a counsellor and later a trustee for Camden Bereavement Service. “She was very good at talking to people, understanding people, giving advice to people on an everyday level. It’s not every day, of course, that you lose someone and she was dealing with quite difficult emotions, but she was always able to take it on board.

“It’s a very interesting area, how relaxed one can be while still caring. We had lots of laughs together, so I’m very keen to keep humour as part of her memory. I don’t want it to be seen as a dark pit into which I have now fallen.”

I tell him that at my spouse David’s funeral my brother-in-law read out something I had written, which ended with a request for any information about the whereabouts of the keys to David’s Land Rover. We never did find them.

“You know, I had to go down to Camden register office to register Helen’s death and I was at the counter trying to fill in forms, and there was a couple next to me also wanting to fill in a form. And I saw the father, I presume, holding on his chest this tiny, tiny little newborn baby. And I thought, yes, that’s it, a new person – one in, one out.”

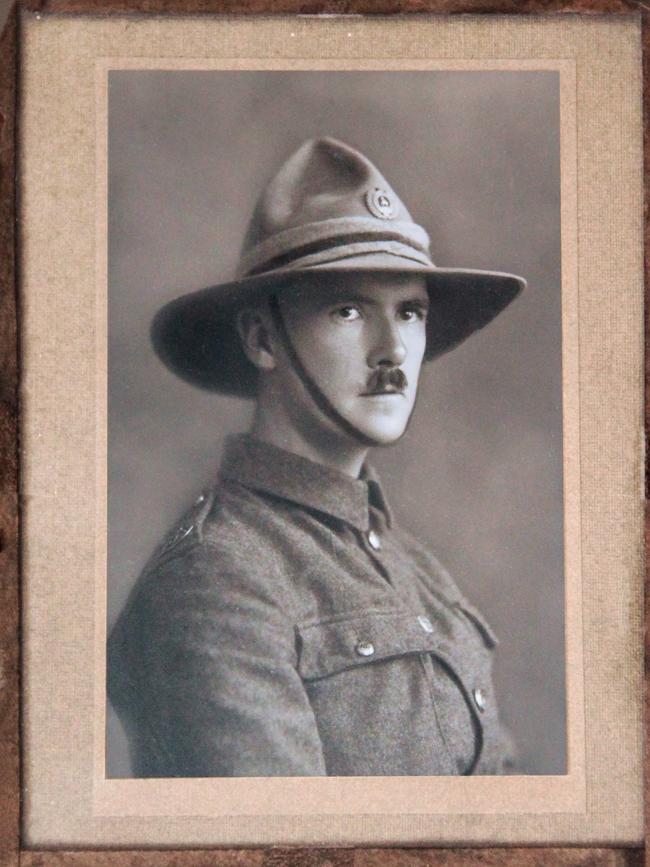

People often hook up with each other at funerals, I have observed – that same need perhaps to add after a subtraction. I also wonder if Palin had felt a desire to write, to capture and preserve a life before it is entirely lost to time. His new book, Great-Uncle Harry: A Tale of War and Empire, a biography, performs this service for Henry William Bourne Palin. This Palin was born in 1884, a son for Michael Palin’s great-grandparents – a don turned parson in Herefordshire married to an Irishwoman saved from the potato famine and brought up in America. Harry was killed by a sniper, or so the official version goes, in 1916 serving with the New Zealand Division in northern France.

“In the 1970s a cousin called Joyce Ashmore brought round some things that she thought might be interesting to the family. I said, ‘Thank you very much,’ and sort of scanned through it. But it was the height of Monty Python, so I didn’t really look at it until the ’80s, I think. I don’t remember when I first looked at the photo of Harry.”

A version of that photograph is on the cover of the book. A young man with a toothbrush moustache wearing his distinctive ridged “lemon squeezer” hat looks stiffly into the distance in the way of photographic subjects of that time. There is something faintly comic about it, faintly Python.

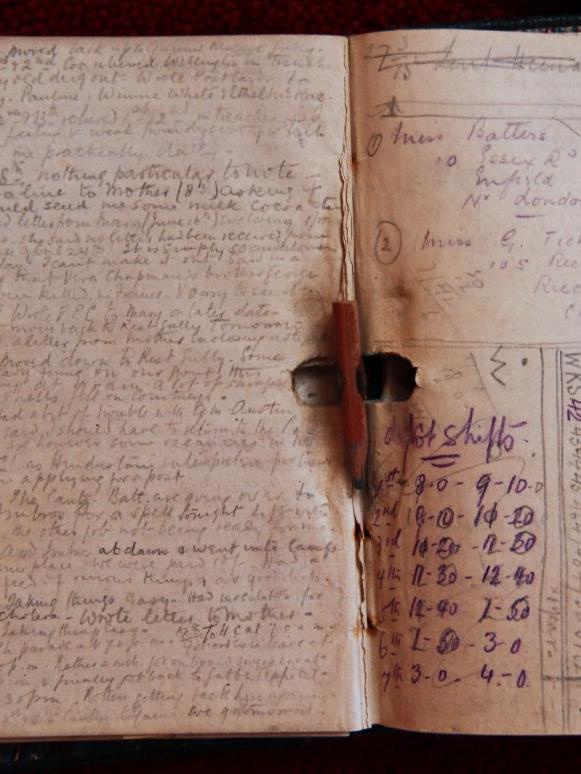

“I asked my cousin who he was and she said, ‘Uncle Harry – he died in the war,’ and that was that.” Harry went to Shrewsbury School in Shropshire, like his father (and where Michael was sent from Sheffield to board), but did not follow him into either academic life or the church. He was a notably low-achieving clerk in India and an unimpressive tea planter in Assam before travelling on to New Zealand, where he found his feet as a farmhand just before the First World War erupted. He joined up and served in the New Zealand Division at Gallipoli and the Somme, keeping the simplest, plainest account of his experiences written in pencil in a thin notebook about the size of a playing card.

“It isn’t Wilfred Owen,” Palin admits.

I leaf through it. It seems to be mostly about cardigans and socks.

“In France they were doing long marches in full kit and they all had sore feet. In Gallipoli... well, they were in the most utterly unhygienic of circumstances, not just heat and dust but decomposing bodies, inches away from them. It’s almost unbelievable but I don’t think he’s exaggerating– that’s just not what he does. He’s just putting it down. Occasionally, after the most significant assaults when a lot of people are killed, he really does get angry and he writes in capitals, ‘THIS IS HELL.’”

Palin the historian provides a summary, lists of casualties, battle orders, the political context, but Harry’s account is personal, unadorned, unselfconscious. He writes about swimming with the lads at Gallipoli, rushing into the sea for a minute or two and rushing out before the snipers could get you. Sometimes they did get you. “Yes, but they still went in. I like the way Harry experiences the war as one of the lads. As someone said about the Falklands, he’s fighting not for Queen – or King – and country, but for the man on his right and the man on his left.”

Does he feel an affinity with him?

“Yes, I do. I feel quite close to him. I think I share with him a reluctance to take the obvious path – I’d be a hopeless manager, or anything organised. Just by a stroke of luck and meeting the right people I ended up being able to make fun of it all, you know?”

The stroke of luck was to be at Oxford in the 1960s. “I think I was more creative than the institution gave me credit for. I wrote an essay every week – ‘Well done, Palin, nine out of ten’ – but I wanted to let my imagination rip. Then I met Terry Jones and I was given a little shaft of light and the door opened up a bit.”

They came to London, started writing comedy, met John Cleese, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman and Terry Gilliam. The origin of Monty Python sounds more like the Beatles than the Goons, a new generation, and in the spirit of the times the Pythons were more like pop stars than a variety act. Nobody knew what they were doing, so they had so sense of limits. “Everything was an experiment and you could do what you wanted, however outrageous.”

The BBC did not know what it was doing either. “They were never really on board. When we tried to describe it to them we were speechless, we didn’t even have a title, but in the end Michael Mills – the BBC’s head of comedy – said, ‘I’ll give you 13 shows, but that’s all.’ And they didn’t really acknowledge that we were on and kept moving us around for the Horse of the Year Show and regional opt-outs in the Midlands.”

This was so frustrating they complained about it to David Attenborough, then the BBC’s director of programs, at a Light Entertainment party. “He said, ‘Yes, but you’ve become a cult because of that and that’s going to do you a lot of good.’ He was absolutely spot-on.”

To continue the comparison with pop bands, were there “creative differences”?

“For the first two series everything seemed fine because we were producing good stuff and people appreciated it. Towards the end of the second series the comedy differences came out and I think John felt restricted, and he went off and did Fawlty Towers, when the others felt we were just starting to do something really good. But as soon as someone wants to move on...”

Another resemblance with pop bands was the reunion, when the Pythons – minus Chapman, who died in 1989 – came together for huge arena shows in 2014. Very rock ’n’ roll, although when bands re-form it is usually driven not by nostalgia but by money.

“I was very involved then in the travel programs and art programs, but there was always a sense that Python was waiting to be revived. Various offers came up, but this friend of John’s who had managed Queen encouraged us to think big. ‘I can get you the O2,’ he said – and he did, 15,000 people. We were only going to do two or three and I was in Scotland and saw on my phone we were doing eight. And it ended up at ten, which was just the right amount because by then we were already saying we couldn’t bear to do another.”

Another loss: Jones, his inseparable friend since Oxford, died in 2020. Palin says it was like losing a limb and his wisest counsellor. The year before that Palin underwent heart surgery for a “leaky mitral valve”. He had an annuloplasty ring installed, and had to give up jogging after 40 years. As he wrote on his website: “My heart scare reminded me that my body isn’t indestructible and if I want to keep it that way I must know when to stop working as well as when to start again.”

A lot, of course, happened between Python unravelling and re-forming, not least Palin’s extraordinary travels. “Funny how in your career the least expected things lead on to something bigger. I was asked to do one of the Great Railway Journeys of the World. It didn’t really fit with what I wanted to do, but when I heard the routes – like New York to Seattle – I said yes, but by the time I got round to it there was only one left, which was London to Crewe. But that led to Around the World in 80 Days.”

The seven-part series aired on the BBC in 1989 (a travelogue classic, it’s available on iPlayer) and demonstrated his skill for seeming at home talking to anyone, an equal angle of approach to everybody.

“I’m very happy talking to people about simple things. ‘How do you milk a yak? Can you show me?’ I’m not very interested in people who are very interesting. It’s like successful people – success can look after itself. And important people are very guarded, what they say is completely programmed, but talking to someone about what their children learn in school halfway up the Amazon works. Because we’re so similar. There are certain basic things about bringing up families, schools, houses, that everybody shares.”

It’s difficult to do that when you’re famous. A good reason to go to North Korea or Iraq – as Palin has done for Channel 5 – is that people there won’t know who you are, which makes for better conversations.

“It’s essential to be with people who don’t know me at all. Actually the Iraqis did seem to know some of my travel programs, although they weren’t singing The Lumberjack Song. I want to get people to talk about themselves, that’s the key thing.

“I’m just very curious, about almost anything – apart from income tax and most technology. Anything that involves the infinite diversity of people is absolutely fascinating to me, as a writer and an actor. But people aren’t really communicating with each other like they used to. Everyone’s looking at their phone. You think you’re connecting with a wider world but you’re not being part of the world that is actually around you at all.

“I had a rant about the state of the world at a do the other night and about how the poor never get to speak for themselves and there are armies protecting the rich and the successful, and there was this round of spontaneous applause. But this actually happened in a rather expensive restaurant. A Python moment – look at yourself, laugh at yourself.”

Does he ever get angry? “Not much. I don’t like getting angry, the lack of control. Idiotic things make me angry, like people dropping litter out of cars. But the state of the world? You’d wear yourself out. There are so many things I feel very uncomfortable about – climate change, those algorithms made up by obliging people who send you your memories, I hate it. So making sense of people at a human level, meeting them, talking to them, that’s what I enjoy most and I try to live my life that way.”

I tell him my favourite part of his North Korea series was when he showed his guide the Fish Slapping Dance from Monty Python on a laptop. “Yes, wherever you are in the world, even North Korea, you can still make people laugh by doing the Fish Slapping Dance. It was one of the simplest things we did on Python. The guide didn’t know what was coming up, she hadn’t been prepped at all, and you saw that North Koreans, like everyone else, are not without humour. They lived in grim circumstances but they weren’t grim in their daily lives, they liked a laugh, liked a drink.”

His delight in their delight is characteristic, which makes me all the more interested in those odd moments of anger. I ask about the TV confrontation, on Friday Night, Saturday Morning in 1979, in which Palin and Cleese defend their hilariously sacrilegious Life of Brian film against a less than impressed Mervyn Stockwood, at the time the Bishop of Southwark, and the satirist turned moralist Malcolm Muggeridge. “What made me angry was that they were so dismissive. And they got it wrong. Python had something to say, Life of Brian was worth debating. Just to dismiss it as tenth-rate comedy... At the end of the interview, when the bishop said, ‘I hope you got your 30 pieces of silver,’ you realised the audience were no longer on their side. Afterwards he came up and said, ‘I thought that went rather well.’”

I love Life of Brian for getting closer to what it might have been like to encounter itinerant preachers in 1st-century Palestine than films such as The Greatest Story Ever Told. Whatever you make of the significance of Jesus of Nazareth, something happened to those who encountered him and it changed the world, in spite of no one really having a clue what he was about. It is the gaps, what is not seen or said, what is not revealed, that becomes compelling – at least for me. And I say all this as a former Church of England vicar. Does Palin have any religious feeling?

“Yes. I was brought up in it but I had too much of it, especially at school, and it became a discipline rather than a faith. I have never been able to deal with the faith bit. I couldn’t make that leap. But I enjoy going to church – I like hymns and music and a place away from the noise outside. But there were times when various people said, ‘Michael, you must realise that you are a sinner and your life needs to change,’ and I say, ‘Well, I know I must sin a bit’” – he laughs – “‘but generally I try to live a fairly decent moral life.’”

So, what’s next for Michael Palin? “I’ve got the next year and a half planned. Book publicity, a tour, then another journey for Channel 5. And another volume of diaries. Can I do all that? I don’t know. Obviously, I’m 80. Quite physically fit, but under pressure? And there isn’t a pathway as there used to be of ‘book, program, book, program’ stretching off into the distance. And also without Helen my life is different. I have more freedom, in a way, than when she was here and I was caring for her. So what do I want to do? Carry on as before? But I can’t because I don’t have the person who has guided my life.”

What does he do with that time? “Sometimes now I just sit things out. And I think it’s OK, but reading all the books you want to read... well, it’s not quite as simple as that. I still want people around in some shape or form. We’re very close to Hampstead Heath and walking there became so important – just getting out, being physical, not having to think of anything but just watching. The leaves coming, new life. Doesn’t have to be heavy-duty. I saw a grey heron on a log the other day and that’s a wonderful thing. I can’t shut down my general feeling for the great adventure of life.”

Helen, he says, still feels close. “She was a very practical, pragmatic person. I have her voice in my head saying, ‘Get on with it.’”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout