To say that is not to ignore the enormous difficulties involved. Not irrationally, Vladimir Putin is counting on the West losing interest as the war drags on. Additionally, he knows that once the northern winter sets in, Germany’s coalition government, whose support for Ukraine has fallen well short of its grandiose promises, will struggle to resist a compromise deal that restores gas deliveries to their pre-war levels.

And with France’s President, Emmanuel Macron, insisting that Russia not be “humiliated”, the EU’s position may become increasingly ambivalent – all the more so as recent public opinion polls in the EU find support for Ukraine softer and patchier than it was when the war began.

Yet an armistice could come at high cost. It is, to begin with, hardly likely to last: over the 1914-2001 period, a third of all ceasefires in interstate wars repeatedly collapsed into renewed conflict.

No doubt a brokered deal would involve promises of non-belligerence, as did the Minsk agreements of 2014 and 2015, which were intended to lead to a negotiated solution in the Donbas; but as Putin showed on that occasion and many others, he shares Lenin’s view that “promises, like pie crusts, are leaven to be broken”.

Rather, the cycle of making and breaking agreements can be ended only by an outcome that convincingly teaches Putin that he can neither suborn Ukraine, transforming it into a Russian satellite, nor dismember it piece by piece, leaving a rump state that would inevitably fail.

Moreover, anything short of a clear Russian defeat would be readily cast by Putin as another confirmation of the West’s impotence and as a vindication of his regime. Overall, Russia’s role as the ally of choice for the Third World’s dictators would be reinforced, entrenching the global trend away from democracy, while the West’s standing, which is still suffering from the battering it took exactly a year ago with the fall of Kabul, would look even shakier.

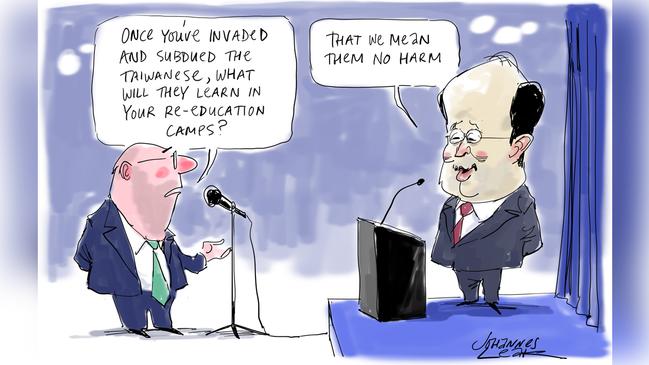

And to make things worse, allowing Russia to profit from the attack could only undermine the credibility of the West’s commitments to ensuring Taiwan’s territorial integrity, encouraging China’s growing adventurism.

None of that means a stinging defeat in Ukraine would lead to a sea change in Russia, much less remove the threat Putin’s regime poses to its neighbours and the wider world.

On the contrary, as American international relations scholar Jessica Weeks brilliantly showed in Dictators at War and Peace (2014), personalistic dictators (that is, dictators who are substantially unconstrained by their domestic political elite) are five times less likely to be ousted in the wake of a military defeat than are the leaders of other types of dictatorial regimes – which is one reason they are about 50 per cent more likely to initiate conflicts that result in defeat.

In part, their resilience reflects the fact they rarely allow rivals to accumulate the power resources needed to mount a credible challenge, instead eliminating them in the bud. Personalistic dictators also survive, however, because they are especially ruthless in using wars as an opportunity for ramping up repression and destroying any remaining opponents – as Putin has so effectively done in the past six months.

Nor would a decisive defeat in Ukraine necessarily bring the Putin regime’s history of aggression to a close. According to a careful statistical analysis by the political scientist Joslyn Barnhart, states that have suffered defeat are 40 per cent more likely to trigger a new war than are states that have not recently been involved in armed conflicts, not least because the former are so often heavily militarised polities run by personalistic dictators.

The risk of defeated states initiating further conflicts is then accentuated by the hubris that characterises those dictators – and by their tendency to surround themselves with advisers who enthusiastically endorse their hubristic fantasies.

For example, in the run-up to his 1939 decision to launch the disastrous Winter War against Finland, in which more than 125,000 Soviet troops were killed, Stalin summarily dismissed the military adviser who warned that the Finns would put up stiff resistance, inflicting enormous casualties that would dint the Soviet Union’s ability to resist a likely German invasion. Instead, Stalin relied on an intelligence report that claimed “the working masses of Finland” would rise up in revolt, “meting out justice on those hostile to the Soviet Union”.

Equally, in mid-1990, Saddam Hussein – who repeatedly claimed that Kuwait had historically been part of “Greater Iraq”, which had been deprived of its “southern province” by Western colonialists intent on fragmenting the Arab states — ignored an intelligence report that concluded an attack on Kuwait would prompt an effective American-led response, preferring to accept his cronies’ assurances that the US was still shell-shocked by its debacle in Vietnam.

All of those forces are at work in Putin’s Kremlin – and will continue to be. But what could durably dampen his regime’s belligerency are the costs associated with a decisive defeat.

Thus, Barnhart and Cambridge’s Ayse Zarakol have shown that states that suffer widespread material losses in the process of being defeated take at least a decade to restore their military capabilities to a threatening level – and longer than that if they are subject to tight restrictions on their access to world markets. Moreover, major powers that have not fully recovered from the costs of losing are 70 to 80 per cent less likely than otherwise comparable states to use force in the two decades following a severe defeat.

It is, as a result, not only crucial to ensure Russia loses: unless it undergoes substantial regime change, its capacity to initiate new wars of aggression must be curtailed. That makes it especially important that it not be permitted to annex the resource-rich areas of Ukraine. And it also underscores the need to retain the sanctions on Russia and bolster their effectiveness.

In a recent paper, the Australian National University College of Law’s Anton Moiseienko highlights just how much Australia could do in that respect, notably by encouraging its allies to craft a multilateral sanctions regime that moves from merely sequestering Russian assets to expropriating them – thus creating a fund for compensating the Ukrainians whose lives have been shattered and helping them to rebuild their devastated homeland.

As the fighting enters a new phase, it is on Ukraine’s battlefields that the future of Taiwan – and hence of world peace – will be determined. The stakes could not be greater; so, too, must be the West’s support for the Ukrainian people.

As the crisis in the Taiwan Strait becomes ever more acute, the best way to deter Xi Jinping from mounting a full-scale invasion is to ensure Russia’s attack on Ukraine ends in a decisive defeat.